Even Paris had seen little like it. One hundred years ago, with the war to end all wars over and an impossibly bright future seemingly within grasp, a riot of new ideas descended upon the city of light.

Staged between April and October 1925, L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) sprawled across the French capital, challenging the future of design, from furniture to fashion, the visual arts, architecture and industrial design. It was a post-war union of the industrial machine age and decorative art, with a subtext of modernity, opulence and exoticism.

Sixteen million people turned up to feel the shock of the new; it was still reverberating years later. In the 1960s, a revival of interest in the exhibition and the style it showcased saw the term Arts Décoratifs shortened to Art Deco. The Paris-based, Polish-born Tamara de Lempicka’s 1925 painting Self-Portrait (Tamara in a Green Bugatti) has come to embody the era, but in the moment, Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann was arguably the star of the show.

The French interior designer grabbed attention despite being only one of 15,000 exhibitors on a vast site that today would overwhelm the city. From the expo’s entrance at the Grand Palais, it spread out along the banks of the Seine and west to the Eiffel Tower, which had been constructed for the Paris World’s Fair of 1889. Car manufacturer Citroen sponsored the Tower’s illuminated light show.

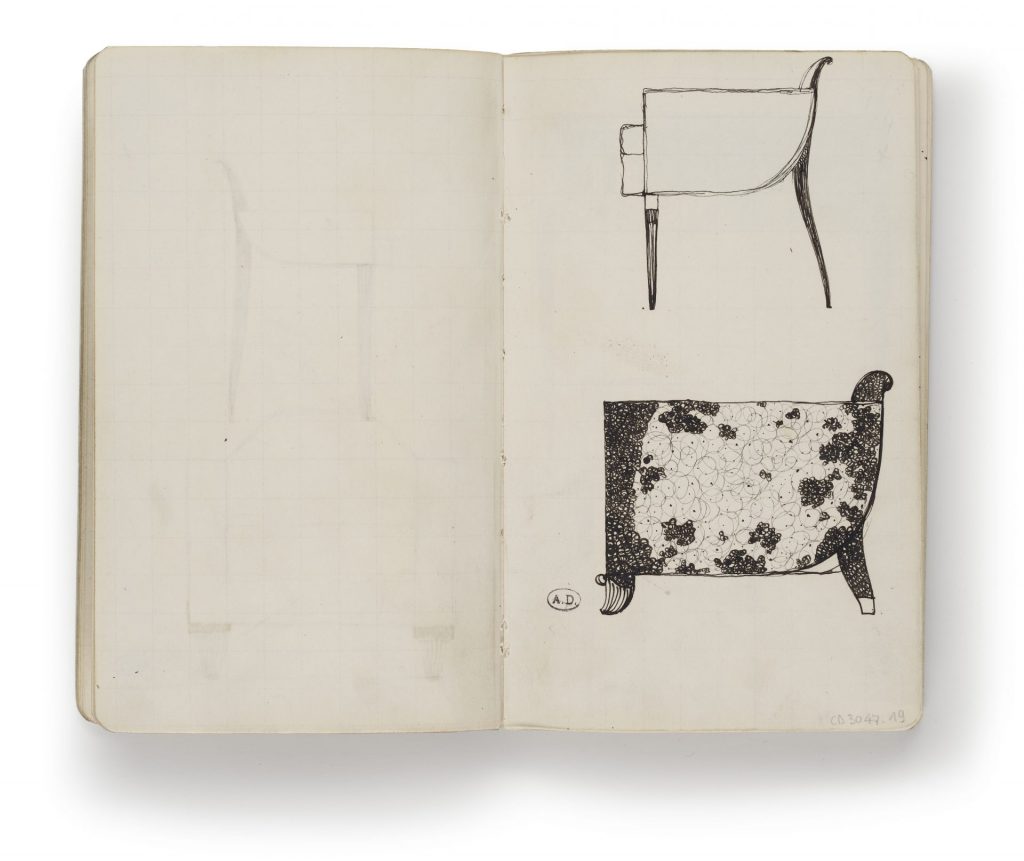

Ruhlmann —

Croquis de chaises

1917

Papier, encre noire

© Les Arts Décoratifs

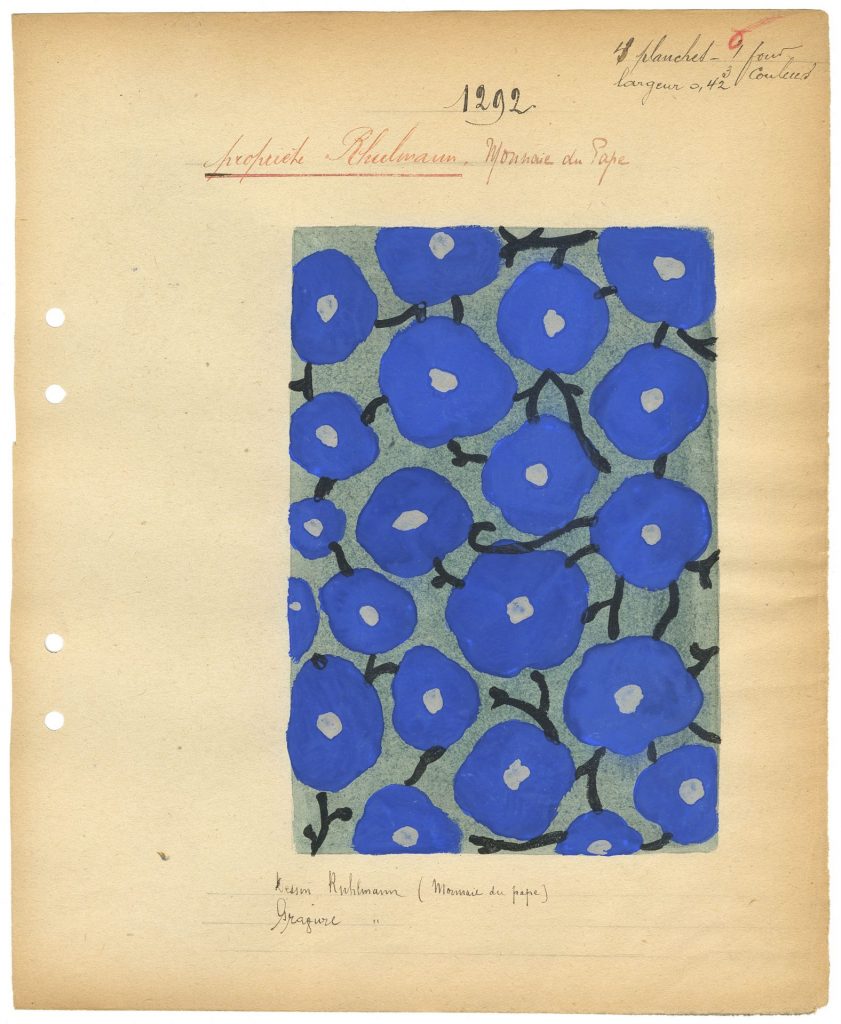

Ruhlmann pour la Société

anonyme des Anciens

Etablissements Desfossé

& Karth —

Projet de papier peint

Monnaie du pape

1914-1917

Papier, gouache

© Les Arts Décoratifs

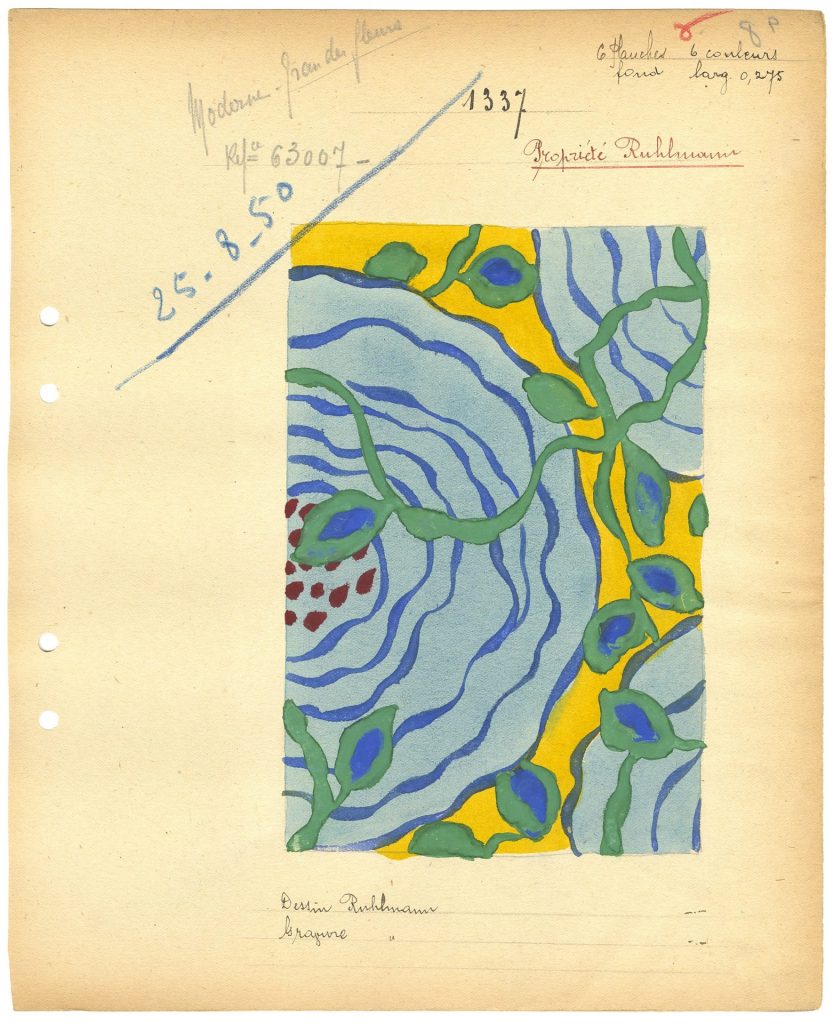

Ruhlmann pour la Société

anonyme des Anciens

Etablissements Desfossé

& Karth —

Projet de papier peint

Moderne Grandes fleurs

Vers 1917

Papier, gouache

© Les Arts Décoratifs

The scale allocated generous space for 34 countries to create their own buildings, or share one, but there were some notable absences. Germany, recently defeated in the Great War, chose not to attend, citing a late invitation (or no invitation).

America chose not to attend, citing that their designers could not meet the criteria set out by the Exposition organisers. Echoing a determination to brush aside 19th-century historicism in art, design and architecture, these stated that: “Works admitted to the Exposition must show new inspiration and real originality. They must be executed by artisans, artists and manufacturers who have created the models, and by editors whose work belongs to modern industrial and decorative art. Reproductions, imitations and counterfeits of ancient styles will be strictly prohibited.”

As hosts, France had the largest exhibition space of all and the work of Ruhlmann (1879-1933), then at the zenith of his career, attracted huge acclaim. It ran counter to prevailing trends – in 1910, the Austrian-Czech architect Adolf Loos’s influential essay “Ornament and Crime” advocated buildings without ornamentation, a maxim that would the be explored in the ‘International Style’ in architecture, where “form must follow function” and design should mirror usage.

Swiss-French architect Charles Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, brought this spirit to the expo, exhibiting his Pavillon de L’ Esprit Nouveau. This ‘white cube’ open-plan modular house, designed by him and his cousin, the Swiss architect Pierre Jeanneret was a visual realisation of a new architectural plan, explored in Corbusier’s treatise Toward an Architecture published in 1920, in which he described the house of the future as “a machine for living in”.

Widely praised and widely criticised, Corbusier’s exposure for ‘white cube’ modernism at the expo helped accelerate its use in architecture across Europe. But the key to L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes was luxury, a currency in which Ruhlmann dealt. He scorned the merely functional and throwaway, declaring that “to create something that lasts, the first thing is to create something that lasts forever.”

Ruhlmann was part of a successful family-run business in paint, wallpapers and mirrors. His niche was avant-garde affluence; exotic and expensive materials painstakingly crafted for the luxe crowd. He rejected utilitarian ‘white cube’ visions and said, “We are forced to work for the rich because the rich never imitate the middle classes. It is the elite which launches fashion and determines its direction. Let us produce, therefore, for them.”

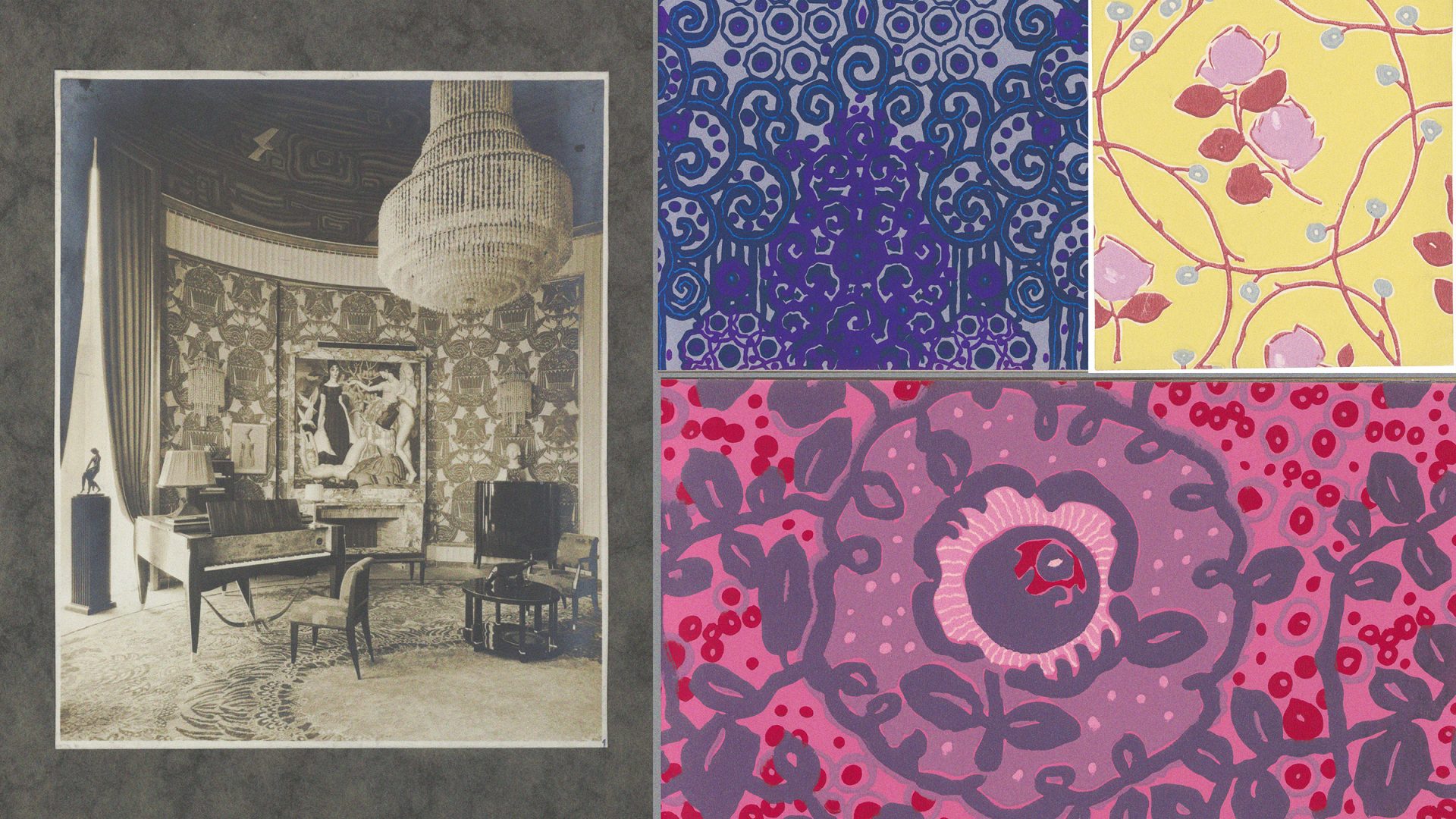

Ruhlmann’s designs were exhibited in the pavilion of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs in “A French Embassy” but showed his avant-garde interior designs and furniture in the Hôtel du collectionneur (House of a Collector)., immediately renamed the Ruhlmann Pavilion. Within it, he visualised “an ideal home”, with nearly 50 designers helping him furnish it in what would now be regarded as art deco styles. It received hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Ruhlmann’s particular genius, and his place in the Art Deco movement, are celebrated in the first of three exhibitions staged in the expo’s centenary year at the impressive Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD) located in the Louvre Palace, at 107-111 rue de Rivoli, Paris. Paul Poiret, Fashion is a Feast, opening mid-June celebrates the haute couture designer who liaised with the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev’s exotic Ballet Russes in Paris and collaborated with French artist Raoul Dufy in the 1925 expo. From October, One Hundred Years of Art Deco explores Arts Décoratifs as an aesthetic trend, highlighting its emergence from Art Nouveau and its glorious heyday, including marvels like the 1928-30 Chrysler Building in New York, designed by William van Allen, which exemplify this period of decorative, commercial modernity.

Before those, there is just time to catch Ruhlmann, Decorator, a display of drawings, wallpapers and remarkable textile samples, to demonstrate Ruhlmann’s ingenuity as a designer. His interior designs for the 1925 Expo are here; the museum owns 26 sketchbooks with original drawings for interiors, motor cars and fabric designs.

On the walls are large-scale photographs of student rooms Ruhlmann designed and decorated for the Cité Université in Paris, confirming his understanding of the modern needs of a student room, the essential factors of light and space, and practical furniture from beds to desks. On show too are wallpapers designed for Desfossé & Karth, and Société française des papiers peints, two of the most important manufacturers in Paris.

Ruhlmann is best remembered for his exclusive, richly-veneered handmade furniture using rare, expensive woods such as Macassar ebony, Brazilian rosewood and amboyna burl, with inlays of ivory. Photographs of interiors in the Ruhlmann Pavilion show visions of luxury for his wealthy clientele.

Ruhlmann’s success at the expo won him celebrity clients, the writer Colette, L’Oreal tycoon Eugène Schueller and aviation pioneer Gabriel Voisin among them, as well as members of American banking families. This golden age would not last – the Great Depression and Ruhlmann’s death at only 54 both came within a decade of the expo closing – but the Art Deco dream seems likely to go on forever.

The centenary exhibitions are at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 107-111 rue de Rivoli, 75001 Paris 1er. Ruhlmann décorateur runs until June 1; Paul Poiret. La mode est une fête from June 25 – January 11, 2026; 1925-2025. One Hundred Years of Art Deco from October 21 – February 22, 2026