Alla Pugacheva’s life story reads like a lesson in late 20-century Russian history. When she was born in Moscow in April 1949, Nato had been founded just days before and the Berlin Blockade was just coming to an end. Under Brezhnev’s tenure, she rose to become the USSR’s biggest singing star and would perform for cosmonauts and for the emergency responders at Chernobyl. She was named People’s Artist of the USSR in 1991 and cemented her position as a peerless cultural icon in the post-Soviet era, coming to be known simply as Alla, the indomitable diva beloved of millions of Russians.

Now, having spoken out against the war in Ukraine just before last week’s general mobilisation, she could influence the next chapter in Russian history.

Pugacheva left Russia for Israel with her Jewish husband, the TV presenter and comedian Maxim Galkin, a month after the invasion. Galkin, who was

born in Odesa, has condemned the war on social media, and after he was

declared a “foreign agent” by the Russian justice ministry earlier this month – in effect making him persona non grata in Russia – Pugacheva wrote on Instagram, “Please include me in the ranks of foreign agents of my beloved country, since I am in solidarity with my husband.”

It is a major blow to the regime to have a figure of her stature speaking out. With a cutting clarity, she articulated what so many Russians must feel, saying that Galkin wants his homeland “to flourish in peace, with freedom of speech, and wants an end to our boys dying for illusory goals, which has turned our country into a pariah state and made life a burden for our citizens.”

Pugacheva’s politics have not always been so clear. In 2014 she signed an

open letter in support of Andrei Makarevich, founder of legendary Russian rock band Mashina Vremeni (Time Machine) and a vocal critic of the occupation of Crimea, but later that year she accepted an Order for Merit to the Fatherland from Vladimir Putin personally, happily posing for pictures at the Kremlin.

Things are very different today. After attending Mikhail Gorbachev’s funeral earlier this month, she praised his transformation of Russia, stating pointedly “most importantly, Gorbachev ruled out violence as a system in politics and holding on to power”.

Pugacheva has been a constant through the past almost six decades of

Russian history, and what she says matters.

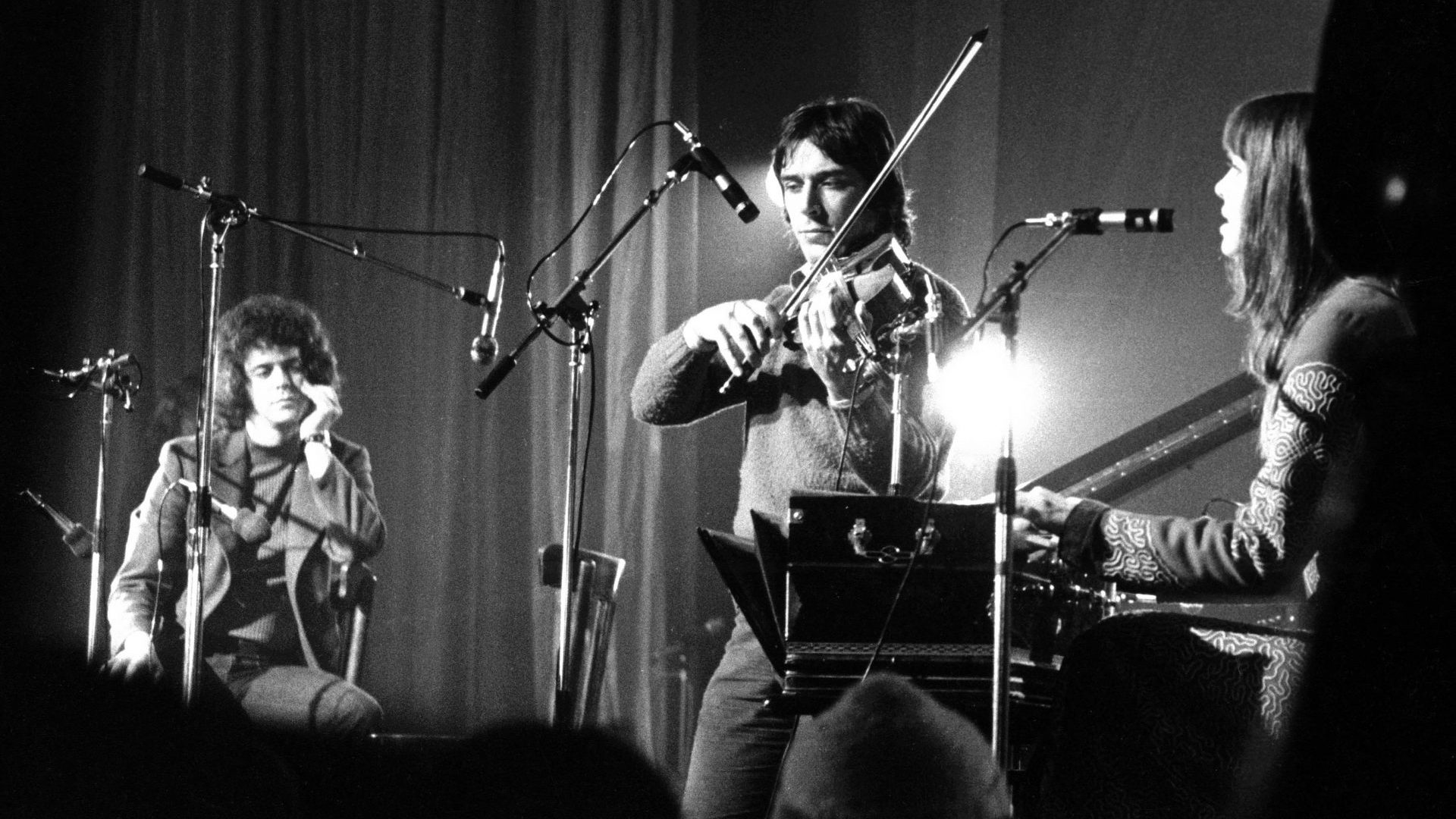

Trained at Moscow’s music schools and honing her live performance through extensive touring with state-sponsored ensembles, Pugacheva first

became known as a solo singer when she was still a teenager as the sombre

sci-fi song Robot (1965) became a minor hit. But it wasn’t until 10 years later,

when she won Bulgaria’s Golden Orpheus international song contest, singing the jaunty tragicomic pop song Harlequin, that she became a big star.

By that time Pugacheva was already divorced and had a young daughter (Kristina Orbakaitе, who has also become a successful singer), and her

colourful off-stage life became a large part of the public fascination with her – her marriage to Galkin, over 25 years her junior, is her fifth. She starred in the semi-autobiographical film The Woman Who Sings (1977), which appeared to give an insight into her private life right at the outset of her fame, and her image as a modern, independent woman caused a sensation.

Her debut album, Mirror of the Soul (1978), which encompassed everything

from Soviet-style pop to funk and blues rock, followed and was a bestseller in the USSR, as well as being released in several languages and serving as the foundation for success in Germany, Sweden and elsewhere in Europe.

As a constant presence on both TV and stage, Pugacheva was a fixture of Russian popular culture by the 1980s, and her appeal was clear. A red-haired

rebel with the mystical vampishness of Stevie Nicks, the down-to-earth brashness of Dolly Parton, and the powerhouse vocal ability of Barbra Streisand, her success in making a career in an age of censorship and state-sponsored culture and then not missing a beat in adapting to the age of the hyper-celebrity – harnessing the power of social media and, as all mega-stars must, launching her own perfume and shoe brand – has been remarkable.

As the Russian president ramps up his warmongering and makes nuclear threats to the West, the commentary of pop stars might seem insignificant. But Pugacheva’s line in the sand could influence Russian public opinion, and as those who have the means flee the country to avoid conscription, the question is raised of what will meaningfully be left of Russia if it loses its cultural icons, too.

ALLA PUGACHEVA in five songs

Робот (1965)

This moody waltz was Pugacheva’s first success. Appearing in the middle

of the space race, its lyrics were addressed to a robot who was once a man and asked in the future “Will we replace hearts with transistors?”

Арлекино (1976)

The song that made Pugacheva a star, it won Bulgaria’s Golden Orpheus

international song contest and was rerecorded in German as Harlekino for

East Germany’s Amiga label.

Женщина, которая поёт (1977)

This was the spectacularly overwrought title song of The Woman Who Sings, the semi-autobiographical film that blurred fact and fiction and made Pugacheva’s private life a source of endless fascination.

Миллион алых роз (1983)

With lyrics by acclaimed poet Andrei Voznesensky, A Million Red Roses would become one of Pugacheva’s signature songs.

Примадонна (1997)

Primadonna was Russia’s entry for Eurovision 1997, the year the UK triumphed with Katrina and the Waves’ Love Shine a Light. It came only 15th of 25 entries.