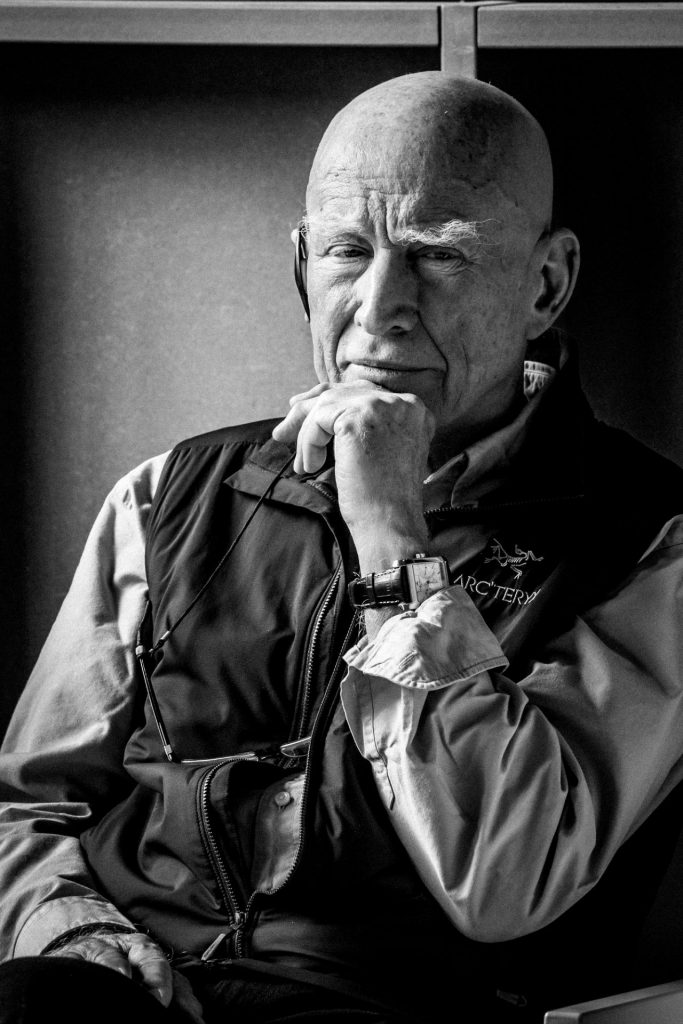

“He sowed hope where there was devastation.” That was part of the message from Instituto Terra, the Brazilian non-profit conservation charity, last week announcing the death of its co-founder, the great Sebastião Salgado.

The 81-year-old was an economist who became an extraordinary photographer, who then became a powerful force for environmental regeneration. Instituto Terra led the reforestation of 17,000 acres of land in Brazil, planting more than three million trees so far. “We can rebuild the planet that we destroyed, and we must,” Salgado once said. It is work that will continue under his partner, Lélia Deluiz Wanick Salgado, and their two sons.

The programme was financed by Salgado’s photography, his trademark black and white images that appear to be lit by God. They explore mankind’s deep connection to places being ripped apart by the “progress” of industry. Perhaps most famous are his almost biblical shots of scores of workers toiling like ants in the Serra Pelada goldmine. His speciality, he said, was “the dignity of humanity”.

Salgado was a 29-year-old working in the coffee industry when Lélia bought a camera in 1971. Within weeks, he had one of his own, then a darkroom, then work as a freelance news photographer. He progressed to become a staff photographer at the industry’s most celebrated agencies – including Sygma and Magnum – before branching out with Lélia on large-scale documentary projects of their own. Subjects included disappearing wildlife, displaced people fleeing war and climate catastrophe, Kuwaiti oil fires, and tribes from the Amazon to the Arctic.

Salgado was proud of forging close relationships with the people he photographed, claiming that the success of the Serra Pelgada photos – which caused a sensation when published by the Sunday Times in the late 1980s – was because “I know every one of those miners, I’ve lived among them. They are all my friends.” His quest for the real came at a cost; he died of leukaemia, his bone marrow function having been badly damaged by malaria contracted on a work trip to New Guinea in 2010.

Yet his beautiful images of people in extremis saw Salgado called by some a hypocritical exploiter. A 1980s campaign for Silk Cut cigarettes, in which tribesmen from Papua New Guinea carried the famous purple silk, proved particularly controversial.

It was a charge Salgado rejected, telling the Guardian last year: “They say I was an ‘aesthete of misery’ and tried to impose beauty on the poor world. But why should the poor world be uglier than the rich world? The light here is the same as there. The dignity here is the same as there.”