It’s no wonder the NHS is somewhat on its knees: Labour has fought at least three general election campaigns warning voters that they had only 24 hours left to “save the NHS” by going to the polls. Three times in a row, voters decided not to do so – and returned Conservative governments of differing strengths.

Perhaps Labour will wheel out the same slogan for a fourth time in a row, rather than try to think of a logical successor – “raise the NHS as a zombie” doesn’t really have much political panache, after all.

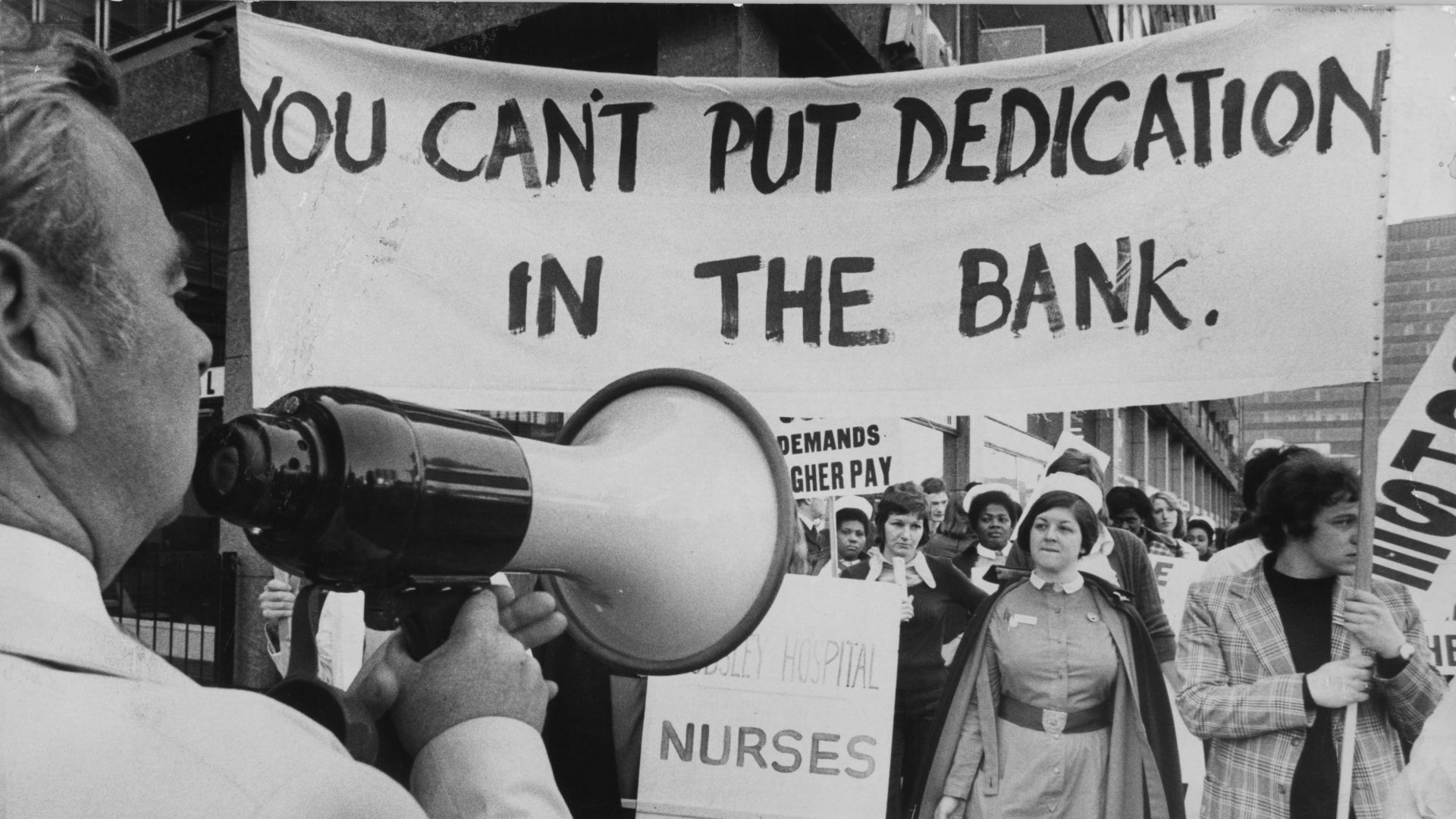

It is certainly true that the NHS is, if not dead, on life support. The problems are most acutely felt by the ambulance service, but they roll right through the whole system. Long A&E waits are now the norm, waiting times for routine surgery are lengthy and the backlog is huge. Even seeing a GP is now something of a struggle.

The consensus on Twitter is that all of this is the result of a deliberate plot. The Conservatives want to starve the NHS so that it can be “sold off” or otherwise privatised, enriching their mates, as mustachio-twirling CEOs laugh into their whisky and cigars.

There’s reason enough to doubt the integrity of certain ministers – ongoing investigations into purchases of dodgy PPE equipment alone show that. But usually anyone who expects there to be a large and nefarious plan tends to be disappointed: the facts rarely stack up as they wish them to.

The honest reality is that running a health service is difficult and expensive, and the UK hasn’t been nearly as good at it as we have liked to tell ourselves for a very long time. A much-shared viral scorecard from the Commonwealth Fund is used to claim that in 2014 the NHS was “the best in the world”.

Looking at the scorecard, there are reasons to be doubtful: the think tank only looked at 11 countries, for example, but there are certainly a lot of top rankings for the UK – on measures like cost, efficiency, provision of safe care, and timeliness of care. But on the measure of “healthy lives” – which included things like life expectancy, infant mortality, and preventable deaths – the UK ranked 10th out of 11.

A claim that you have the best healthcare system in the world might, you would have thought, focus a little more on how well it does to keep people healthy – or at least alive. The collapse has not been as bad as the same social media NHS accounts make out either: the latest Commonwealth Fund scorecard, from 2021, rates the UK as 4th out of 11, but on the “healthy lives” measure, the UK is actually ninth, rather than 10th.

The rest of the world – including European countries with much larger states and more generous welfare provision – has generally looked to the NHS and said “thanks but no thanks”. It is not the only way to provide universal healthcare, it’s not the cheapest way to provide it, and it certainly doesn’t provide the best outcomes – it’s not bad, but it’s not brilliant, either.

Any suggestion that the whole thing could be sold off or privatised fundamentally misunderstands how the NHS – and private healthcare – operates today. How much of the NHS needs to involve private companies before it’s “sold off”? How much is already private, without its supposed champions knowing about it?

GPs, for example, almost all work via private practices that receive funding for taking NHS patients – almost every surgery is a small, partnership-owned business. Most pharmacies are private businesses, too, taking contractual payments from the NHS for prescriptions and other services.

Drug companies are, famously, international corporations – kept well in check by the NHS as a near-monopoly buyer (purchasing is something the NHS is generally very good at). And those much-maligned doctors and nurses who work in private practice to help people jump NHS queues – they’re the same angels who work for the service.

More than half of consultants make at least some money from private practice, and nurses and junior doctors supplement their income that way, too – only a minute fraction of medical staff work purely for the private sector. There are clear issues of conflict of interest – among other problems – with this arrangement, but it is clear staff would only give up their right to work in this way at a significant cost.

There isn’t a conspiracy against the NHS because there doesn’t need to be one. It is falling apart because we haven’t funded it enough – even though it has received a better funding settlement than any other department. We have not had the honest conversation as a nation about what a real, functioning NHS would look like.

It would involve paying to train more doctors and nurses, and it would involve paying a lot more for social care – including some people eventually paying by selling their homes, perhaps after they and their partner have died, so it damages inheritance rather than leaving vulnerable people to move. Social care would need to be integrated into the NHS and into NHS trusts, to avoid the game of pass-the-patient that is played daily around the UK.

It would take a lot of time for visible results, and it would cost a lot of money. Taxes would have to go up – it couldn’t come from the super-rich alone. And if we didn’t reform the NHS at the same time, we could end up spending much more money just to stop our middling system becoming a bad one.

For so long as we treat the NHS as our national religion and play an annual game of acting as if it is under terminal assault – like US Conservatives declaring an annual “liberal war on Christmas” – we contribute to its decline. We spend so long putting it on a pedestal that we don’t see the wear, the damage.

The NHS is not a monument, nor a church. It is a public service, and we need to judge and treat it as such – not as some precious bauble that our political opponents want to smash. We have an ageing populace and we know that trend is set to continue. If we want the NHS to be functional for when today’s 60-year-olds are in their 70s, we need to have those honest conversations now.

We’ve had “24 hours to save the NHS” three times before, after all, and we opted not to do it. Are we willing, as a nation, to abandon the comforting allure of Tory plots to kill it off, and make “saving the NHS” more than a slogan?