According to his account book, Sir Edward Dering, a 25-year-old Kentish aristocrat, passed an agreeable day in London on December 5, 1623. With the winter chill closing in he bought some woollen socks, treated himself to a tin of marmalade and then lunch for himself and his servant. Feeling chipper, he flipped sixpence at a beggar before heading for the highlight of his excursion: the yard on the north side of St Paul’s Cathedral where London’s booksellers and stationers had their shops.

Dering stopped at Edward Blount’s establishment at the sign of the Black Bear and, being a particular fan of the theatre, liked what he saw on display. He purchased a couple of quarto play scripts and a folio volume of the works of Ben Jonson, as well as a book of religious texts in Latin by a Jesuit preacher named Drexilius in order perhaps to reassure friends – or even Blount himself – that his reading was not entirely frivolous.

Most significantly, he also bought two bound copies of a compendium of theatrical works whose pages were so new they still bore the tang of fresh ink – one for himself, the other perhaps for a friend with similar theatrical interests. Whatever the motivation, as a cold wind whipped up the brown waters of the Thames that chilly day, Sir Edward Dering made the first recorded purchase of what has become known as the First Folio of the works of William Shakespeare.

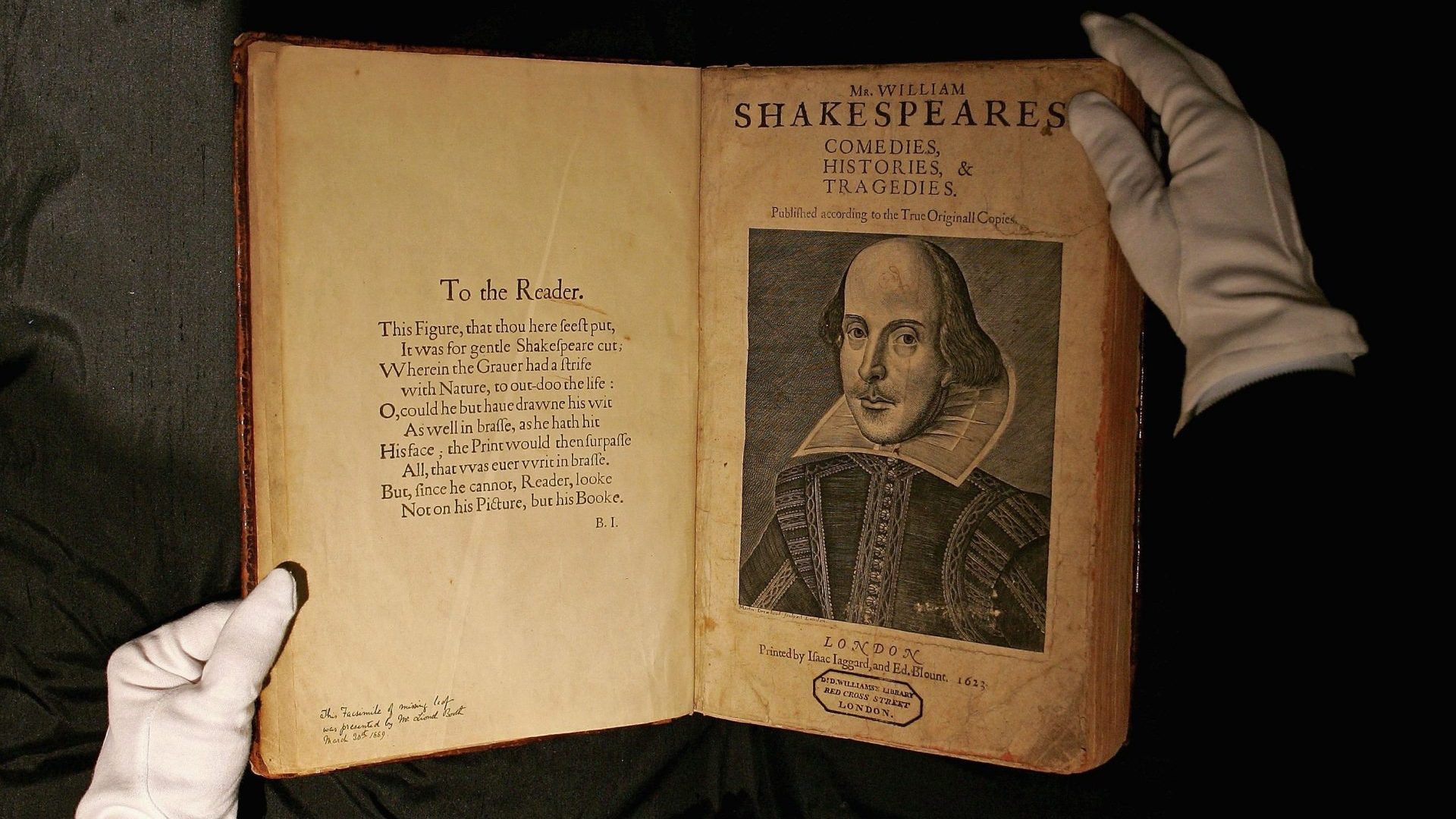

That first printing of Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies – published seven years after the playwright’s death – has been granted an exalted place in the history of literature and drama. The First Folio contains the texts of 36 Shakespeare plays across 908 large-size pages in an edition of around 750 copies, of which 235 are known to survive.

Like some kind of secular, limited edition holy grail, First Folios rarely come on to the market. When they do they command eyewatering prices, most recently in October 2020 when an edition sold at Christie’s in New York for $10m, around £7.6m.

The First Folio fetches such prices because it is effectively the foundation manuscript of the Shakespearean legend and, by extension, modern English literature. Some individual plays had been printed before but in cheap, unreliable, effectively pirated editions. It was only in the First Folio that Shakespeare’s works were collected together in versions as close as possible to what their creator intended.

Not only that, without their inclusion in the First Folio there is every chance we would have lost a whopping 18 of Shakespeare’s plays including Macbeth, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar and The Tempest.

The collected edition of Shakespeare’s works was the brainchild of John Heminges and Henry Condell, actors in the King’s Men company of which Shakespeare was also a member, possibly inspired by Ben Jonson’s publication of his own works in folio form in 1616. Jonson would write an eloquent poetic dedication to open the First Folio.

Viewed four centuries on from its first appearance in the shadow of a cathedral at the heart of London, the story of the First Folio feels on the face of it like a very English one, yet the book’s production and dissemination owe a great deal to Europe and European culture.

A month before Dering became the first documented owner of a copy, the book had been entered into the Stationers’ Register on November 8 by Blount and Isaac Jaggard, the younger half of the father-and-son duo who co-produced the books with Blount.

While this is usually taken as the official birth date of the First Folio, it was not the first recorded mention. Heminges, Condell, Blount and the Jaggards had been working on the folio for some time.

Given the sheer number of plays required to be sourced and edited before being typeset this is hardly surprising, there must have been new manuscripts turning up all the time, probably just when the self-appointed scholars thought they had finished at last.

This might explain why the book had been announced as a published work a year earlier in 1622, when it appeared in the English language supplement to that year’s catalogue for the Frankfurt Book Fair.

A single-line announcement, the First Folio would have been easy to miss, listed beneath a wordy description of a two-volume set of questions and answers discussing the Book of Genesis and above a pamphlet reproducing a sermon given at Huntingdon on how sickness of the body begins with sickness of the soul. But it was there.

“Playes, written by Mr William Shakespeare, all in one volume, printed by Isaack Jaggard, in fol.”, it said, the first collection of Shakespeare’s plays being announced not in London, but at a book fair in Hesse.

It would of course be an exaggeration to say the First Folio’s roots are entirely European, but even this continental aspect of its origins is not particularly surprising as, at the turn of the 17th century, Britain enjoyed significantly closer ties to Europe than it did even in the years leading up to Brexit.

The same is true of its leading playwright. We know very little of Shakespeare’s life outside the plays and sonnets and there are several years in which nobody knows where he was, but as a jobbing actor and playwright it is likely that in his younger days in particular, Shakespeare would have made a significant portion of his living as part of a troupe touring the continent.

English touring companies were extremely popular in Europe around the turn of the 17th century, their well-trodden itineraries taking them all over, from Bohemia to Scandinavia. Indeed, Poland’s first purpose-built theatre opened at Danzig in 1600 specifically to accommodate English productions. Shakespearean scholars have suggested that the Bard’s apparently detailed knowledge of Kronberg Castle at Helsingør, as described in Hamlet, could well have been the result of a visit he had made himself.

The strongest direct connection between the First Folio and Europe is Edward Blount. As well as his role in the book’s genesis, this son of a journeyman tailor had a profound influence on European literature thanks to his remarkable ability to recognise and publish potential classics, many of which endure today.

Orphaned at a young age, his father’s trade and legacy allowed Blount to be educated at the Merchant Taylors’ school where, crucially, he learned to read in Latin and Italian. In his mid-teens in 1578 he was apprenticed to the Stationers’ Company under the tutelage of leading Tudor book publisher William Ponsonby, where he stayed until in the 1590s he was able to open his own bookshop and publishing house in St Paul’s Yard.

Once established, Blount’s entire career was spent with one eye on literary developments across the English Channel. Indeed, his first published volume was The Profit of Imprisonment, a 1594 translation of a popular French poem that was followed three years later by Charles Tessier’s Le premier livre de chansons, a collection of French and Italian songs, and then in 1598 by John Florio’s A Worlde of Wordes, the first commercially available Italian-English dictionary.

This Europhilic outlook defined Blount’s publishing life. In 1603 he produced the first English translation of Montaigne’s essays and, a decade later, the first English edition of Don Quixote. In 1623, as well as the First Folio, Blount published an English edition of The Rogue: or the Life of Guzman de Alfarache by the Spanish writer Mateo Alemán which, like the Shakespeare Folio, opened with a celebratory verse by Ben Jonson.

As well as commissioning translations, Blount was also a key importer of books from Europe – in 1624 he arranged the purchase of volumes published in Paris, Lisbon, Burgos and Barcelona for one customer alone.

As for the first Folio’s most overtly European contribution, it was possibly Blount himself who commissioned the engraved portrait of Shakespeare that fills almost a whole page opposite Jonson’s dedicatory verse, the work of the Flemish engraver Martin Droeshout. It is not a particularly good engraving, most likely derived from a now-lost contemporary portrait as Droeshout was barely 15 when Shakespeare died and likely never even met him, but with its bald head, thin moustache and faintly wry expression, his image has become the best-known representation of the Bard, adorning everything from biscuit tins to tote bags. But, just as the book had been first announced in Frankfurt, this most English of engravings was made by a man from Flanders.

Unsurprisingly given Blount’s role in the fluid exchange of literature between England and the rest of Europe, the First Folio made its way across the Channel. The first recorded evidence of an exported copy was confirmed as recently as 2009 when infra-red photography revealed that one of the 82 First Folios held by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington was inscribed in 1647 by its then owner, the remarkable Dutch poet, composer and diplomat Constantijn Huygens.

A friend of Rembrandt’s who enjoyed regular correspondence with Spinoza and Descartes, Huygens was a voracious and polymathic scholar whose library had a strongly Anglophilic slant. As well as a First Folio, his shelves bent under the weight of works by John Donne, Geoffrey Chaucer, Ben Jonson, Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser as well as a collection of English poems by various authors.

Huygens’ Anglophilia was enhanced by several visits to England as part of his diplomatic duties in the early 1620s, during which he met Donne and Jonson, was knighted by James I and possibly even saw one or more of Shakespeare’s plays performed in London. Hence, when he learned of the existence of this new collection of Shakespeare’s works, Huygens knew immediately that it was an essential addition to his European library.

It’s 400 years now since a Kentish nobleman handed his poor servant a hefty pile of books to carry including 1,800 large format pages of Shakespeare’s plays in two calfskin-bound editions, in which time the First Folio has become the most sacred artefact in English literature.

Yet within those pages, from the lived experience of the playwright himself to the artist who engraved his image to the book’s visionary publisher, there is infused a hefty helping of Europe, exemplifying its important position in the open exchange of culture and ideas between England and the continent that was typical of the era.

Indeed, the First Folio is the direct product of, as Huygens himself noted in his 1622 poem The Exiled Shepherd, the continuing cultural legacy of “the chalk-white strand of Britain… To which shores our Flemish lowlands were connected long ago”.