Everything about the work of Iranian-born Shirin Neshat is political. It is also poetic, and always personal.

She is known for the remorseless way she lays bare the iniquities of her homeland from which she has long exiled herself with perhaps her photographic series Women of Allah the most powerful of her work. Striking images of steady eyed women in chadors sit or stand expressionlessly, handwritten verses from Iranian feminist poets superimposed on their image with a gun, pointing at the camera or close to hand ready to be used. They speak of defiance and martyrdom, both beautiful and damning.

But now, at the Photo London fair which opens on September 9, the Iranian-American photographer and film-maker is, for the first time in her career turning her lens on to the USA, her adopted country, with Land of Dreams.

It is a complex combination of stark black and white photographs of more than 100 people and two films shown on split screens, that aims to expose the dangers of an oppressive society. It is set in the United States of Donald Trump but it could be the Iran of the mullahs. Eerily metaphysical and uncompromisingly realistic, it could be an allegory of repressive societies everywhere.

Why now? After all, she has lived in the US since 1996 having first left Iran in 1975 to study at Berkeley University, California, and never felt it possible to live in a country dominated by the ayatollahs who seized power in the revolution of 1979. Inevitably, her work has always focussed on Iran and the middle east because, as she says: “In a way it was to feed my anxieties and obsessions about a lost past.”

We talked on Zoom from her home in upper state New York, too early for her to have painted on the familiar slash of mascara she wears under her eyes, on a screen that jumped and froze but could not blur the passion and clarity of her vision.

“I did not feel I had the licence or the right to make work that examined American culture but, you know, my life evolved a few years ago when I realised, okay, this period of looking back at a culture that I no longer connect with must come to an end. It was time to say goodbye to this chapter. Having lived in America for so long as an immigrant I felt I had some perspectives to this country and what I like and dislike. It’s not like I was a tourist.”

This change of focus coincided with the Trump years and the need to channel her personal angst into a reaction to the political shift that came with the former president against many minority groups. It helps explain why many of the people in the photographs are like her – immigrants or dispossessed such as the Hispanic, Native and African Americans, many of whom were drawn to the American dream of freedom and opportunity. She can identify with them as a ‘nomad and an alien’ for, as she says: “I can’t remember where I was when I looked like everyone else, spoke the same language.”

She and her husband and collaborator Shoja Azari chose New Mexico as the location for the work because its spectacular desert landscape of dusty valleys and sharp peaks reminded her of Iran while still being very American.

“We wanted to have this possibility where at some point the viewer wasn’t sure whether we were in Iran or in America,” explains Neshat, who admits to the nuances of the project by listening to Persian music while they were driving in an American urban landscape.

“Oddly enough I found there were a lot of parallels between Iran and US and that was really like an opening of a new chapter for me. With Land of Dreams, I found that other doors were opening, other subjects and ideas that I absolutely want to focus on in this country but always, always, always from a personal lens.”

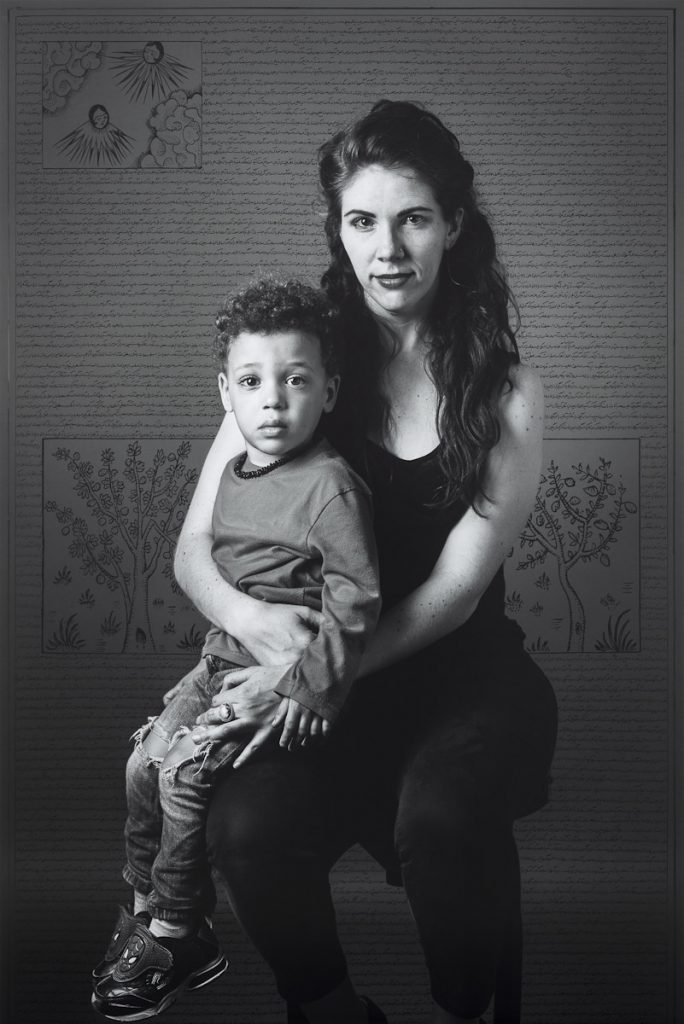

The photographs, black and white, often against a neutral background, depict her subjects in similar poses with eyes fixed on the camera, hands always in the same position. There is a weary defiance about them all.

She photographed more than 200 people, asked them about their lives and backgrounds, talked about their dreams and in some cases recorded the interviews in calligraphy, or for those with more elaborate dreams, added drawings such as birds, cows, and lizard-like creatures which she copied from an ancient book kept in a library in Tehran.

The book appears in one of the two films which make up Land of Dreams, in which a young Iranian art student named Simin is filmed travelling around New Mexico photographing local residents in their homes and tentatively asking her subjects about their most recent dreams.

She meets a woman who dreamt of her home being destroyed by “dirty ragged children” who smashed her elephant figurines, an anguished former soldier still haunted by witnessing a nuclear explosion – “I hear people screaming. The sun is going to fall, the sun is going to fall” – and a woman who has a nightmare that her village has been destroyed.

The parallel film, The Colony, finds the protagonist working in a vast, utilitarian hall lined with desks, each with a scientist who is steadily researching people’s dreams, including those Simin has already met. It is an Orwellian state in which the mind is subject to mass surveillance.

Neshat explains: “Simin plays an agent whose job was to collect people’s dreams but she becomes emotionally invested in her subjects and enters their dreams. Some of their nightmares remind her of her own nightmares, her own dilemmas and anxieties.”

In her research, Simin breaks the rules of the Colony by tearing out a page from the same Persian book which inspired the illustrations which accompanied the photographs and which she hopes will help her interpret dreams.

She is caught and questioned by a bearded inquisitor, who, coincidentally or not, looks like a menacing mullah, who warns her: “When and if the dream catcher enters the dreamer’s dream loss of identity will take place. No punishment is necessary as the dream catcher shall go mad.”

She is expelled from the facility. We see her walking through a deserted, ramshackle warehouse, a symbol of the violence, war, and devastation which has become a nightmare for Simin, who has herself been made homeless and suffered military force.

Neshat says: “What was interesting for me was that while this woman was an agent for the Iranian colony she was, on a personal level, coping with a very authoritarian and oppressive, controlling environment.”

The two videos together are both disturbing and poignant, especially for Neshat who once confessed: “In my dreams I always see my mother pushing me away but I came to realise that this is not my mother but my motherland rejecting me. I am not welcome in any of the cultural places in Iran.”

Which in part explains that there is another P in her lexicon at play here along with the personal, the poetic and the political. The paradoxical.

Yes, the cameras have been turned on New Mexico but the work is just as much, maybe more about Iran for Neshat has not quite escaped the ‘realm of nostalgia’ or the pull of her homeland as she once put it.

She says: “It is a very loose reference to what it is like to live in Iran, constantly dealing with an extremely authoritarian government in which everything is heavily controlled.

It is obviously exaggerated and absurd but the judge in the film is like a mullah, a clergyman of higher power, the leader, like Trump, someone who represents tyranny and controls peoples lives. It’s a symbolic character, not a realistic character.”

Nonetheless, though she says the subject is not directly about Iran, she does admit that her point of view will always be from an Iranian perspective. “We have this great expression – you can take an Iranian out of Iran but can never take Iran out of an Iranian – but I still feel this is the most honest way of making work about America while being very faithful to the experience of an Iranian-American immigrant. That is something that is important to me.”

But are the themes of autocratic pressure, injustice and repression merely contained to Iran and her adopted country? Is it too simplistic to present this as Trump versus ayatollah Khameini? Iran opposed to the USA?

“I think people like Khameini have brainwashed certain people in Iran and Trump has managed to do that to a large number of people in America with, you know, his conspiracy theories.

“Trump does it in a very ideological way right v left, Republicans versus Democrats, and the anxiety that he creates among the people is very similar to the way Khameini does it in the name of God. He creates anxiety against America, against Israel, always creating this image of an enemy, promoting fear, rallying the people around.”

For Neshat, the ‘absurdity of politics and fanaticism and rhetoric’ is a universal problem.

“It could be the Soviet Union, it could be South Africa, Brazil, any form of community dealing with oppressive, corrupt governments. When I’m creating an atmosphere like The Colony I am not really talking only about Iran, I am talking about the whole atmosphere of authoritarian environment.”

Yet it seems she is still frustrated by her self-imposed exile and angry at the injustices she sees taking place in her country. Above all, she has an almost visceral longing for her homeland.

“You have to understand that I am from a generation that is very sore and damaged by the revolution of 1979 and the separation from the country, from the family, so the idea of this part of Iranian history showing up in my work is almost natural.

“This is part of my history, my anger and rage at a state which has been so controlling of my destiny.”

Photo London, September, 9–12. Somerset House, Strand, London; Photo London Digital, September, 9–28. photolondon.org

A full-length feature film, Land of Dreams, based on the original and starring Matt Dillon and Isabella Rossellini will be shown at the Venice film Festival until September 11.