Once again, a Labour prime minister faces an epic economic crisis as Donald Trump’s tariffs deepen an already dark context. Spending is scarily tight, taxes may rise, and fiscal rules could be broken. Growth is sluggish.

No one knows what Trump will do next, not even Trump. The future is hazy.

Fortunately for Keir Starmer, there is a guide for him from the recent past when two previous Labour prime ministers faced impossibly demanding crises, with illuminating lessons about what to do and what not to do. Starmer needs to learn them as a matter of urgency.

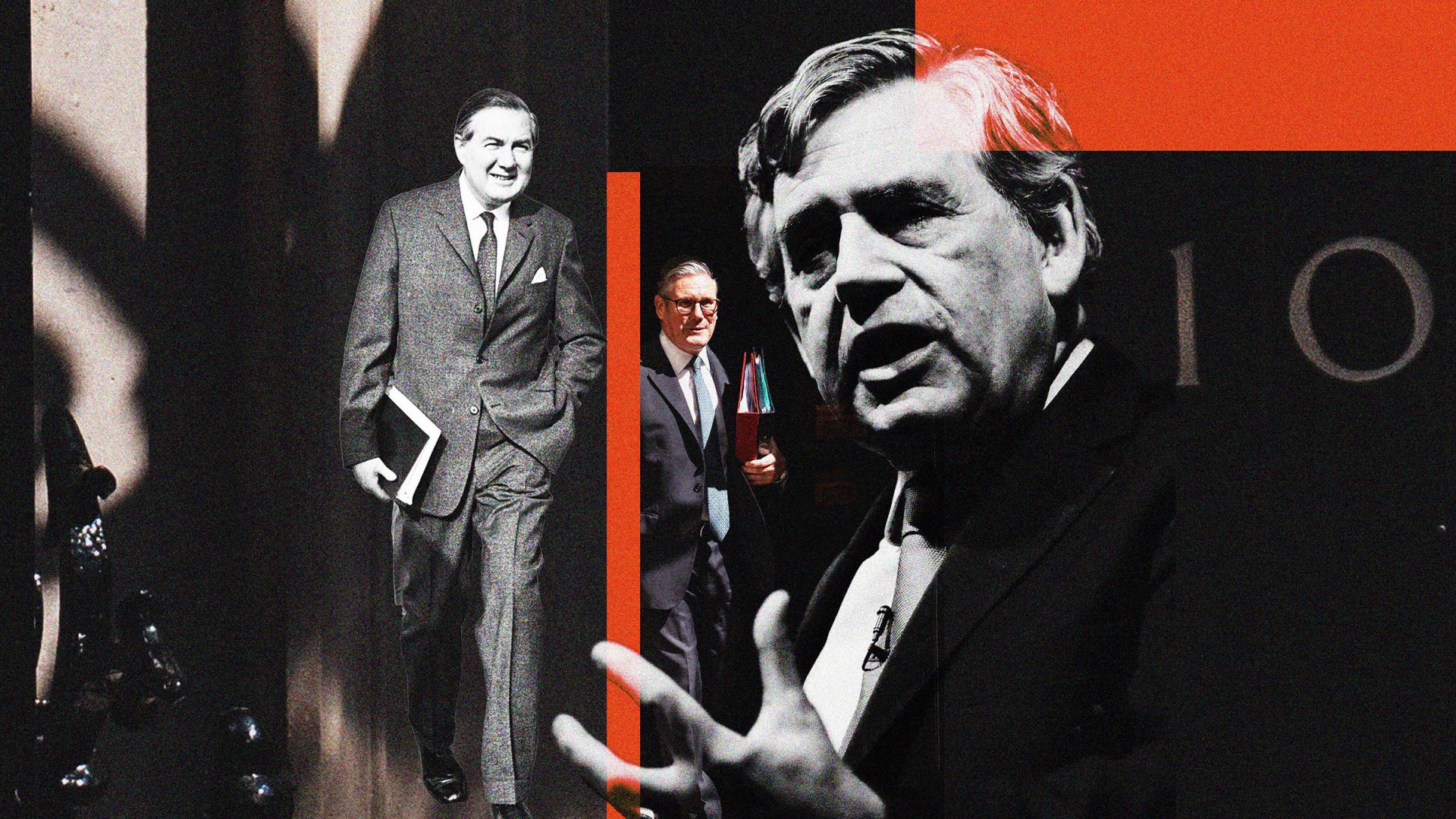

In 1976, Britain appeared to be on the verge of bankruptcy when the prime minister, Jim Callaghan, and his chancellor, Denis Healey, negotiated a loan from the International Monetary Fund. More than three decades later Gordon Brown was prime minister and Alistair Darling his chancellor during the global financial crash in 2008. The current situation may not seem as dramatic as those two, but the challenges facing Starmer are on a similar scale.

Should he borrow more or will that make the situation worse? Should he cut public spending or increase it in an attempt to boost the economy? How to win the political battle at a time of fragility and disillusionment?

Callaghan sought to address these questions in 1976, at a time when he led a formidable cabinet split three ways over what to do. He and Healey were in no doubt that they needed to negotiate a loan with the IMF and agree to slash public spending. Labour’s philosopher king, Anthony Crosland, disagreed with the scale of cuts. Developing his Alternative Economic Strategy, which included import controls, Tony Benn opposed the cuts altogether. Both had strong support in the cabinet and beyond.

The prime minister and chancellor prevailed. They got their loan, and cuts were imposed. At around this time, Callaghan famously declared that it was no longer possible for a government “to spend its way out of recession”. The speech was taken to mark the end of postwar Keynesian economic policy.

There were many consequences from this dramatic sequence. Instead of gaining credit for stabilising a wild economic situation, Labour was associated with a panic-stricken move. A government going “cap in hand to the IMF” became a Tory motif for decades.

By appearing to concede that public spending was no route to growth, Callaghan gave acres of space to his highly ideological opponent, Margaret Thatcher. In the mid to late 1970s, she was seeking to popularise her commitment to monetarism. Thatcher preached that “my father never spent more than he earned in his grocer’s shop… and a country cannot spend more than it earns”.

Her homily was nonsense, but accessible nonsense. Callaghan had cleared the way with his insistence that a government could not spend to revive the economy.

Later in his brilliant memoir, Healey revealed that the dire Treasury forecasts in the mid-1970s were wrong. The economy was not in as bad a way as was assumed. There had been no need for the government to negotiate with the IMF in the way it had felt impelled to do.

There are two big lessons for Starmer arising from a sequence that doomed Labour to what seemed like eternal opposition. The first is about the pivotal relationship between prime minister and chancellor.

Callaghan was far more steeped in economic policy than Starmer is. He had been chancellor but lost his job when he was forced to devalue the pound in 1967. But Callaghan took a similar approach with Healey as Starmer has done with Rachel Reeves. He trusted Healey’s judgement and saw it as his duty to back his chancellor, with few questions asked of him.

The relationship was rightly seen as rock solid. But Callaghan was too supportive. He should have scrutinised the Treasury claims more sceptically than he did. As is often the case, the Treasury was wrong. In some respects, the cabinet dissenters were right.

Unlike Callaghan, Starmer faces no cabinet rebels at the moment. His government is young. Ministers are terrified they might be sacked if they utter a word out of place. That means only he can scrutinise his chancellor.

There are no cabinet heavyweights to do so. Reeves will not always be right. The Treasury will not always be right. So far, Starmer has given Reeves at least as much space to do what she wants as Callaghan gave Healey. I am told that in their private discussions he did not question any aspect of Reeves’s July statement, which included the politically disastrous cut in winter fuel payments, nor did he greatly scrutinise the autumn budget.

Prime ministerial subservience to the power of the Treasury must change. This does not mean ceasing to support his chancellor. It does mean constantly questioning the assumptions behind economic policy and the policies that follow. Even David Cameron challenged George Osborne sometimes, in spite of their close friendship.

Starmer has no feel for economic policy. He urgently needs a substantial adviser, or ideally a unit of economic advisers. He needs to be more involved in the search for such committed expertise. So far he has left the attempt at an appointment to Liz Lloyd, the latest figure from the Blair era to become central to Starmer’s No. 10 operation.

The second lesson is about the battle of ideas. At a time of change and turmoil, the ideological premise on which a government acts matters greatly.

In the late 1970s, Thatcher had the stage to herself. Having conceded ground, Callaghan ceased to battle Thatcher in terms of ideas. He was baffled as to why she spent so much time in the US debating the role of the state with right wing Republicans and with those similarly inclined in the UK.

But this gave her the confidence to argue that the state was the obstacle to people’s lives and not a liberating agent. In spite of the best efforts of Neil Kinnock and Roy Hattersley in the 1980s to show how the state could free people rather than stifle them, Thatcher continued to win elections.

Starmer leads in almost the opposite context. In the recent emergency Commons debate, there was support across the political spectrum for the government to “take control” of British Steel. Nigel Farage had been the first leader to propose public ownership. Perhaps he was being opportunistic. What is revealing is that he regarded nationalisation as a vote-winner.

We are in the era of a more active state. But Starmer needs to own the concept and explain around the clock why the idea of an active state suits the priorities of his government.

Like Callaghan, Starmer seems irritated by ideas. His time as Director of Public Prosecutions moulded him into more of a technocratic administrator. He is in a political battle now and needs to seize the moment in a way that Callaghan did not in 1976.

The contest with Farage and Reform is easily winnable. But if Starmer loses the battle of ideas or refuses to engage with it he is doomed, as Callaghan was.

In the autumn of 2007 when Northern Rock was heading towards bankruptcy, there was no consensus around the issue of public ownership. Gordon Brown was against such a move at first, fearing headlines about Labour going “back to the 1970s”. When he had no choice but to take the bank into “temporary public ownership”, Cameron and Osborne held a joint news conference accusing him of exactly what he had feared.

Brown became bolder in the global crash a year later. He borrowed to save the banks, and borrowed even more to pay for a fiscal stimulus to prevent a recession becoming a depression. He succeeded, but never found a way of winning the ideological argument.

It was Cameron and Osborne who were stuck in the past, viewing the crisis through the distorting prism of the 1980s and proposing Thatcherite solutions such as real-terms spending cuts. But they won the argument. If there was a deficit, deep cuts were the only solution.

Brown could not find a way of explaining why Keynesianism had already prevented a depression and could help to reduce the deficit. He was up against the Conservative leadership, the Treasury, parts of his own party, and of course the mighty media.

What would be an equivalent act of boldness for Starmer? As the US turns away, he needs to move much closer to Europe. In an era of muscular economies battling it out, the US, China, the EU, British exceptionalism looks more absurd than it did during the Brexit referendum. I understand why in the early phase of a crisis he seeks a “cakeist” solution, getting close to both the US and Europe. But soon there will be a choice: the UK being a vassal state of the US, or an active player in Europe, not only in relation to defence but also trade and economic growth.

Europe should be his choice. He needs to win the argument that such a course is the right thing to do. A lesson from 2008 is that boldness is necessary, but nowhere near enough.

Steve Richards is host of the Rock N Roll Politics podcast. He presents Rock N Roll Politics live at Kings Place on May 8 and July 17