It looks like, in the USA at least, inflation has peaked, with year-on-year Consumer Price Inflation falling back to 7.7% in October. The Federal Reserve has more than doubled interest rates since July, to 4%, with a series of aggressive hikes aimed at taking the steam out of the economy.

Globally, a similar picture is emerging. While the headlines are dominated by consumer price rises, global producer price indexes have been falling since the summer – including here.

The average cost of shipping a 40ft container – which rocketed in 2021 as the world recovered from Covid-19 lockdowns – has been falling for most of 2022 and, on crucial routes like Shanghai to Los Angeles, is down 89% since last November. Another classic “canary in the coal mine” chart, the United Nations index of world food prices, is now back to where it was at the start of the year. Vegetable oil prices, which spiked massively as Russia invaded Ukraine, are now below where they were before the war started. In the UK, however, the peak looks likely to come later – in this month or next. But as the heat comes off the UK’s cost of living surge, we are going to be surveying the wreckage for years to come.

In the first place, inflation figures only measure the rate of increase. The fact that inflation’s lower doesn’t stop stuff being dearer than it was before. The Office for National Statistics, which measures the cost of basic foodstuffs over time, says a four-pint bottle of milk, which cost £1.17 in September 2021, now costs £1.52; tea, frozen vegetables and frozen chips are all about one third dearer than a year ago. And with real wages falling fast, the average disposable income of a UK household in 2024 is going to be 7.1% lower than it was in 2019.

So what can we do? And why has the UK been among the worst hit by global inflation?

The debate among economists revolves around three basic questions: how much of this was caused by the springback of growth post-Covid; how much by the restructuring of global markets in response to the Covid supply shock; and how much by Russian price manipulation, as part of its hybrid warfare strategy? What’s absolutely clear is that almost none of it was caused by excessive wage demands.

As the post-Covid surge subsides, and the panic buying of gas, oil and grain in response to Russian aggression eases off, we are left with the possibility that core inflation might be permanently higher due to the way trade rivalries have intensified, as major countries saw how vulnerable they were in the scramble for PPE, ventilators and the like.

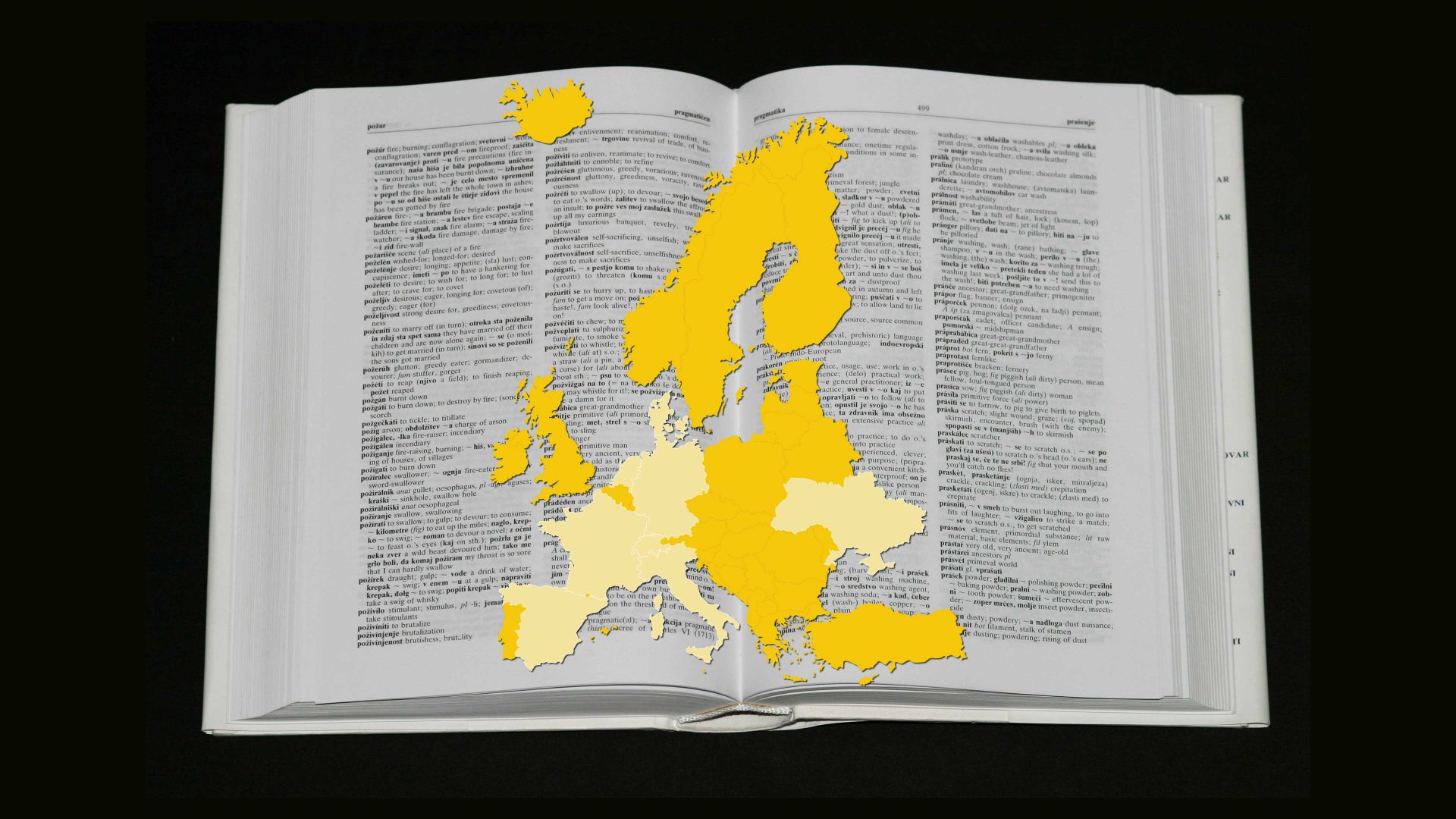

Both China and the USA have launched self-reliance policies in key technology areas, like semiconductors. Trade barriers, including export bans, are proliferating as geopolitical tensions rise. Meanwhile, corporations that were once happy to see production processes distributed across several continents are now consolidating their operations regionally.

Just as globalisation provided access to cheap labour and cheap commodities, the era of deglobalisation does the opposite – with the added complication that capital itself is no longer cheap, because of the interest rate hikes central banks have made in response.

And the UK – for the obvious reason of having chopped off its own free trade agreement with the nearest regional bloc – looks highly vulnerable. Even with weak wage bargaining power, we ended up with the highest and latest peak among developed countries, and then – for good measure – the Truss government inflicted a needless 18-month recession by losing market confidence. So it may be time for the UK to abandon its 2% inflation target, raising it to 3 or even 4%.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, CPI will collapse over the next 12 months, hitting its 2% target in early 2024 and entering a two-year period of deflation after that. As the former IMF chief economist Oliver Blanchard points out: once it falls to 3%, are people really going to clamour to keep interest rates tight just achieve the last mile, and overshoot the target into deflationary territory?

Indeed, a recent study by economists at the International Labour Organisation, who surveyed Google searches for the word “inflation” across 37 countries, showed that below 4% most people don’t pay attention to the CPI index – so fears that anything above 2% sparks an inflation spiral may be unfounded.

The double-digit inflation we’re living through is, for certain, bad news: for workers, who are taking a once-in-a-lifetime hit to real wages, and for the public sector, where councils, hospitals and schools are being forced into emergency service cuts by rising prices.

But if sticking to 2% – and the high interest rate policies it demands – deepens and lengthens the UK’s recession, that is the result of a political decision. Central banks converged on the 2% norm in the 1990s, in the belief that it gave them wriggle room to cut rates in a recession. Since 2008 we’ve known that was wrong. Now – faced with the first episode of stagflation since the 1970s – it’s time to rethink.

A new inflation target, set initially at 3% with a “no big deal if it goes to 4%” clause, would remove the Bank of England’s power to instruct governments to inflict recession, and give the economy headroom to grow. It would feel like the end of an era but that’s only acknowledging the truth: the era of cheap capital, labour and goods is probably over.