Those who seek to divide Britain and Europe might do well to remember that the exchange of ideas and skills between the island and the continent

has been going on virtually since the dawn of civilisation. It is written in stone, as the celebration of the summer solstice at Stonehenge this week may remind us.

We were once physically attached to mainland Europe. Migrants walked across the fertile plains of Doggerland, now lost beneath the North Sea, and

after that disappeared, small boats crossed the Channel, bringing neolithic farmers from the Mediterranean to replace the earlier Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and establish the first fixed settlements.

From about 2400BC came the most significant prehistoric movement of people from Europe to Britain, that of the Beaker people. Having originally

migrated west across Europe from the Eurasian Steppes, they brought to

Britain new rites and practices, including burial with the deceased of the distinctive, patterned pottery “beakers” that gave them their name.

Their arrival, as copper and then bronze began to supplant the stone tools of Neolithic Britain, also signalled a dramatic change in the population of our island, as Beaker genes replaced those of the earlier inhabitants over a relatively short period. How this happened remains the subject of fierce debate among and between archaeologists and geneticists. In the absence of strong evidence of violent acts of conquest, it may be that the native Neolithic people simply died out as new pathogens arrived with the migrants – or perhaps they were simply edged out by the more sophisticated arrivals.

Yet the traffic was not all one way: Neolithic Britain very probably pioneered the building of monumental stone structures, including stone circles of all sizes, avenues of standing stones or menhirs, earth-banked henges and a vast array of different-sized burial chambers.

Images Group

Some of the earliest structures were the stone circles and chambered cairns and tombs of Orkney, near the Neolithic ritual settlement of the Ness of Brodgar. One interpretation is that the fashion for building stone circles like the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness may have originated in Orkney and spread out from there, although there is evidence that some circular structures in Cumbria may possibly predate those on Orkney.

What is not disputed is that there was a shared culture of stone monuments on the western seaboard of Europe, extending from Iberia to Brittany and including Britain and Ireland. Putting dates on stone structures is challenging: it is possible some continental structures may predate those in Britain and Ireland, pointing more towards a shared culture, rather than an export of ideas from Britain. Other Neolithic circles have been found as far east as the Italian Alps and Bulgaria, while some Mediterranean islands, such as Corsica and Sardinia, boast numerous tombs and other structures from the period.

What Britain’s Neolithic inhabitants most certainly did give to continental Europe was the Langdale Axe. These axes were quarried high in Cumbrian

fells and especially at the surviving Neolithic quarry site just below the summit of Pike o’ Stickle, high above Langdale. They were carried down to

sites around the perimeter of the Lake District for finishing and polishing.

Some finishing sites were on the coast, from where they were “exported” to Ireland, and many made a journey across the Pennines to Yorkshire or the south of England. Some went further still, with examples having turned up across Europe. Because the many axes that were found showed no sign of having been used, the contemporary view is that they were thought to possess a mystical and possibly ceremonial quality, having been sourced “close to the heavens”. They were, in effect, simply too good to use.

In her extraordinary book about Corsica, Granite Island, the historian and diarist Dorothy Carrington writes of the discovery in 1948 of Neolithic carved menhirs half-buried in an overgrown orchard. Although not all in their original positions, some of these now encircle an olive tree on the extensive Neolithic site of Filitosa, reflecting an enduring obsession with the very concept of the circle, but at the same time unlike any other stone circle, because the carvings on them depict faces.

In my own book, Ring of Stone Circles, I suggest that the building of circular structures seems to have roughly coincided with the beginnings of agricultural cultivation and the exchange of a nomadic lifestyle for a more settled one. I consider the physical properties of the circle: an eternal shape with no beginning and no end, and the notion of an afterlife or spirit world, as some people at least began to live longer lives.

Certainly we can draw parallels with the annual circular nature of life itself: the coming and going of the seasons and the need to predict these as agriculture evolved. In Britain in particular some stone circles, Stonehenge among them, do indeed incorporate both solar and lunar alignments, with the latter requiring a multi-generational understanding of the cycles of the moon. In other instances, it seems that we – in our desire for one consistent explanation – try hard to find such alignments when they may never have existed. In short, some stone circles may have been no more than meeting places, or “trading posts” where navigable rivers and overland routes met.

Although the Beaker arrival signalled the beginning of the end for Britain’s monumental megalithic structures, including the much-evolved Stonehenge, the circle tradition appears to have endured into the Iron Age in some parts of Europe. Hunn Gravfelt, in the Norwegian county of Østfold, is a site comprising nine stone circles and a number of burial mounds dating from the late first millennium BC. There are also two Iron Age circles at Lundeby, south of Oslo, each comprising 13 stones.

In my research into Neolithic Britain, and Cumbria in particular, I was trying

to find any conceivable traces of the long-forgotten culture that spawned these enduring circular monuments. The surviving circles (of which there are more than 1,000 in Britain), henges and dolmens are the most obvious and enduring legacy, but we can infer the existence of Neolithic routeways that were subsequently adopted by others, including the Romans. Of “art” there is little or no evidence of figurative works from Neolithic or Bronze Age times: the cave representations of animals at Cresswell, on the Derbyshire-Nottinghamshire border, are from much earlier, though carvings of deer were identified using laser technology at Kilmartin Glen, a rich Neolithic landscape in western Scotland, in 2021.

What have endured are the enigmatic cup and ring markings etched into rocks from Scotland to northern England and across Europe from Scandinavia to Greece. They echo designs found all around the world from the Americas to Australia, but remain mysterious. We have no idea whether they served a function, such as route-marking, or were abstract extrapolations from natural forms in the rock.

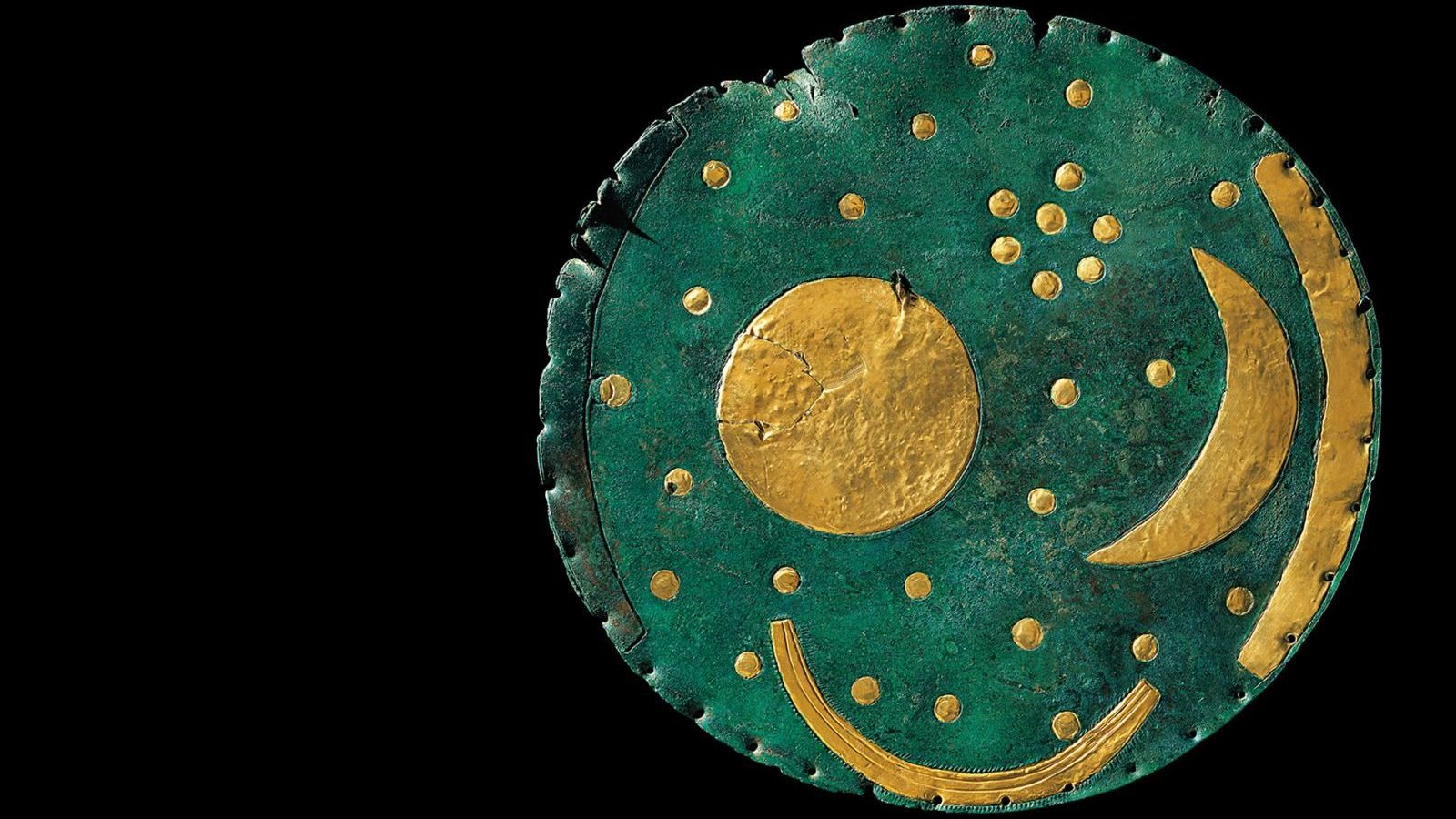

It is exceptionally difficult to explain the true purpose of the icons of Neolithic or Bronze Age Europe with any certainty: unlike those of ancient

Egypt, or indeed the late Bronze Age culture of Mycenaean Greece, the people who lived in most of prehistoric Europe had no written language, leaving us to rely on a combination of scientific deduction and speculation. What we can be sure about is the enduring appeal of both circles and monoliths – from the Olympic rings to crop circles; from Cleopatra’s Needle to the steel monoliths that began appearing all over the world in a 2020 internet craze.

Ring of Stone Circles: Exploring Neolithic Cumbria, by Stan Abbott, is published by Saraband, price £9.99