Almost 100 years to the day that Benito Mussolini’s fascists staged their “march on Rome” and seized power, is Italy heading for a second coming? It’s a flippant question for the 21st century, perhaps, but one that’s unavoidable, now that the favourite in this month’s Italian general elections is a “post-fascist” party whose roots extend back to allies of Il Duce.

The right-wing Fratelli d’Italia (FdL) “Brothers of Italy”, even has two descendants of Mussolini in its ranks, along with members and supporters who worship the fascist wartime leader. Party officials have been filmed giving the fascist salute, and the FdL emblem is the tricolour flame, the symbol of the Movimento Sociale Italiano, “Italian Social Movement”, a neo-fascist party set up after the war by a group of Mussolini’s supporters.

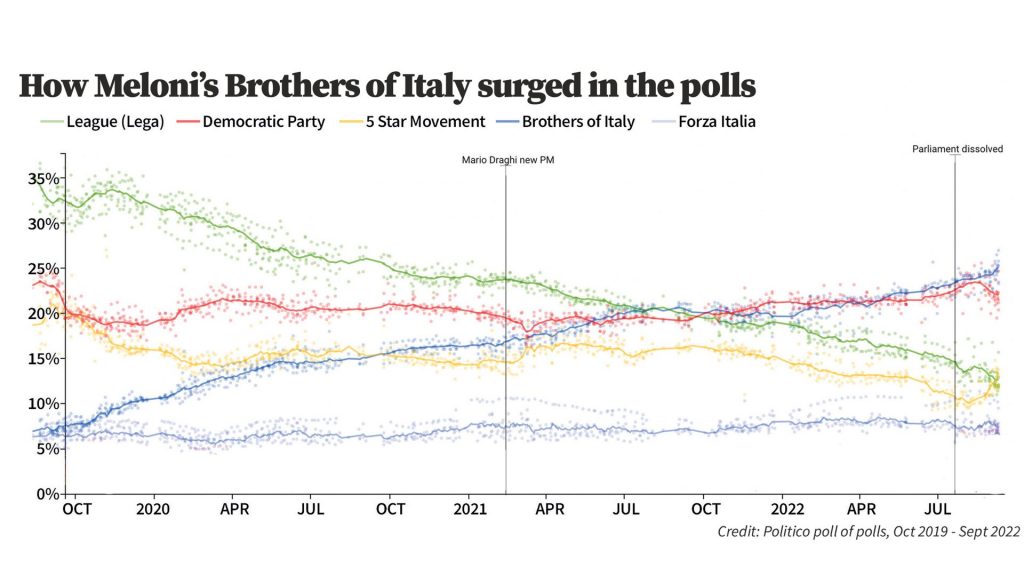

In many ways, the FdL is a pantomime villain of a party, made up of fruitcakes and loonies and at the 2018 election, it won a meagre 4% of the vote. Now, it’s in the political mainstream and its leader Giorgia Meloni is in contention to become Italy’s first woman prime minister, the first since Mussolini to run on an overtly far-right platform.

This has been coming for some time. Disgruntled voters have been trying out and discarding leaders for years in the search of someone who can put a stop to economic decline and social division. In 20 years there have been 11 short-lived governments. It always ends in tears.

The arrival of the hard right was brought forward by the resignation in July of prime minister Mario Draghi, whose tenure ended in a row with his coalition partners. Meloni, together with her allies – the right-wing firebrand Matteo Salvini and the wily former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi – was ready to strike.

Their popularity is worrying for European leaders. Right-wing populist governments tend to be disruptive and unpredictable. Only two weeks before the Italian election, the anti-immigrant, populist Sweden Democrats created shockwaves by coming second in Sweden’s general election. Their success was all the more shocking, as the country is widely regarded as being the archetypal European social democratic success story. Hungary and Poland succumbed long ago to populism, and the same political tendencies are rising in Spain and Portugal, and remain a threat still in France. The danger from illiberals remains.

The European left more broadly, is worried by what it sees. That sense of alarm was captured in comments made recently to Euractiv by Iratxe García, the leader of the Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament. García worried that an extreme right-wing government in Italy “would further undermine our EU founding values of equality, democracy and rule of law.” Not only that, “it would weaken the unity and solidarity we now so much need in the face of Putin’s aggression, due to their nationalist agenda,” she said.

Italy’s former prime minister, Enrico Letta, leader of the Democratic Party (PD) and the left-wing bloc, has said that, if the right gets into power, “I fear it would be over for Italy.” In that case, goodbye La Dolce Vita. While the left is divided and trailing in the polls, there’s above 45% support for the right-wing alliance of the FdL, Salvini’s League party and Forza Italia, Berlusconi’s party. It was Berlusconi who first brought a post-fascist party into government in the 1990s. Not only that, he bragged about it. “We let them in for the first time,” he said. “We legitimised them.”

To the outside observer, Meloni, who was barely known outside Italy until this year, has made sudden and remarkable progress, but her rise is actually the product of a long term plan and a lot of determined marketing. Even her appearance is part of the package. An overweight young junior minister in Berlusconi’s government, she slimmed down, softened her appearance, adapted a vest top and trouser combination, and discovered pastels – after all, who would be scared of someone in powder blue? Her brown hair is now golden and, for publicity pictures, photoshop is her friend,

Luciano Cheles is a professor at the University of Grenoble and author of The Political Portrait: Leadership, Image and Power. “In the far right, women are appreciated if they’re young and pretty – they are impressed by superficial beauty,” he told me. “So she has to improve her looks.” A former right wing MP, Il Duce’s niece, Alessandra Mussolini, had even posed naked for Playboy.

Four years ago, Donald Trump’s aide Steve Bannon, once darling of the US alt-right, was courting her as part of his aborted attempt to bring together populist parties across Europe. This week, comparing her to Margaret Thatcher, he gave her his endorsement. “I’ve said for years that Italy is the worldwide laboratory for the populist-nationalist revolution,” Bannon said. “The world needs to be watching, very attentively, Giorgia Meloni, and taking note.”

As she approaches power, Meloni has been trying to shed the baggage of her past, and that of her party. She has, she says, detoxified FdI by expelling all the “fascist nostalgists and racists,” but she has not changed any of the party’s symbols. Cheles, a historian of visual studies, has found a lot of what he considers to be clear fascist signalling, from objects and emblems to words and phrases, including the repeated use of the phrase, “History will prove me right.”

Few think Meloni is a fascist today, although she can be seen as a young teenager on French television praising Mussolini. But she clearly needs the support of Italy’s remaining fascist sympathisers, to add to the middle class voters she is wooing. Italy never quite purged or confronted its fascist past, after they hanged Mussolini and switched sides in the Second World War. The fascist strain remains. They are good activists, their obsession ensuring they dedicate their lives to the party.

Francesco Galietti, co-founder of political consultancy Sonar, sees Meloni as “a mystery wrapped in an enigma. No-one knows for sure what she is about. She has been on an evolutionary path for several years.” He knew Meloni from her days as a junior minister, when she was shy and insecure. He’s both impressed and perplexed by her transformation.

“She is a selective populist,” he said. “You can see she rails against LGBT rights and abortion and at the same time whenever Ukraine or China are on the agenda she is firmly on the side of the UK and the US. It’s kind of odd, because this kind of ‘sovereigntist’ is normally pivoting to Russia and China.”

She has positioned herself as centre-right, serves as president of the European Conservative and Reformist party in the European Parliament, and regularly name-checks Margaret Thatcher, the British Conservative party and Ronald Reagan. It’s a mark of her strategy’s success that observers have begun to accept her positioning, and the alarmist articles have largely been replaced by a more nuanced view of a woman claiming Italy had “handed fascism over to history for decades now”, and having geeky conversations about Lord of the Rings.

“It would be too easy to present Meloni as the heir to fascism,” Federico Niglia, associate professor of history at the University of Foreigners in Perugia, told me. “I wouldn’t overestimate the burden of the past. Never forget that neofascism is not conservative. Conservatism has another intellectual history.”

Ultra-sensitive to media portrayals, when the New York Times depicted her as extreme, she released a video in three languages to assure the foreign press that they had nothing to fear from her.

Unlike Salvini, once the rising star of the right and a volatile, angry politician, she has managed to publicly distance herself from the illiberal European autocrats she once admired, including Vladimir Putin. Meloni supports sending arms to Ukraine. But there’s still a worry that Italy might stray from Europe’s sanctions on Russia after a cold winter with high energy prices.

She has been convincing as an Atlanticist, while on Europe, although she taunts the European Union on the election trail, she may well be more bark, less bite. Italy is important in the bloc as a founder and net contributor, and is also currently dependent on Covid recovery funds.

“Why pick a huge fight with the European Commission when lots of money is at stake?” Daniele Albertazzi, professor of politics at the University of Surrey, asked, rhetorically, when we spoke. “Besides, a government can have 60 percent support but it will disappear in a month if they do anything stupid that alarms markets.”

As he prepared to leave office, Draghi urged Italy to stick to its pro-European, pro-Western foreign policy and sober economic plans, and Meloni looks like she has taken note. She said that she might follow the line of “Draghi, but better”, and may even appoint ministers who were close to him. Draghi is said to be “nice to her” and is liaising with Meloni.

Her manifesto is the usual mix of overambitious spending, regressive tax cuts, pension increases and cuts to handouts, which may be little more than signalling. It recalls some of the right-wing conservative instincts of Liz Truss, with whom Meloni has been portrayed on social media as one of the new “right wing girl bosses”.

Even so, Meloni has made missteps on the way, such as releasing a video of a Ukrainian refugee being raped by a migrant in a bid to inflame anti-immigrant sentiment. Meloni and Salvini have spoken of pushing back or even sinking boats carrying refugees to Italy’s ports. They are also proponents of the Great Replacement theory, the idea that white, European populations are being supplanted by immigrants, many of them non-Christian. It’s clear who their scapegoats will be. Asylum seekers – or indeed any group, including Roma people – could find themselves under a new, intense scrutiny. Unpleasant deals on how to deal with immigrants could be signed with countries such as Libya, where the EU already has an agreement.

And this is where a new right-wing Italian government could find its illiberal safety valve. While showing a moderate face on the international stage, they’re likely to go hard on social issues domestically, where nobody can interfere.

LGBTQ rights is a particular target issue. Meloni is strongly “anti-woke”. In a speech in Spain to a crowd from the far-right Vox party, she became hypnotically shrill and heated as she listed some of her cultural beliefs: “Yes to the natural family, no to LGBT lobbies; no to Islamist violence: yes to sexual identity, no to gender ideology.” She has even railed at a character with “two mummies” in the new series of that Boris Johnson favourite, Peppa Pig.

But her encounter with an activist with a pride flag who jumped on stage at a rally in Cagliari is emblematic of her softly-softly strategy. Pushing away the security guards, she welcomed 24-year-old Marco Marras to the stage, asked the crowd to give him a round of applause, and allowed him to speak on gay marriage. He was delighted. But, crucially, she didn’t budge from her initial opposition to gay marriage or gay adoption. You have civil unions, she said, and adopted children should have a mother and a father.

“I respect and try to understand your point of view,” she added later. “I hope that sooner or later, you will be able to do the same.

She is firmly against abortion, a position that has put her in the firing line of many celebrities, including Chiara Ferragni, the social media influencer and designer. She regularly expresses gratitude that her mother, who raised her alone, did not choose a termination. She has promised not to change the law on this – she would not dare. Abortion has a lot of support in Italy. But she could enforce the law in full, including the little-used provisions to offer women alternatives to abortion, which in practice means encouraging women to consider their situation until it is too late. Disingenuously, she has spoken of giving women the “right to not have abortions.”

A look at the Abruzzo region, the first part of Italy to come under FdI control, is instructive. As well as making it harder for migrants to access social housing and refusing them food vouchers during the pandemic, the authorities have made efforts to deter and shame women who are seeking terminations. This included ignoring laws allowing women to take abortion pills at home and proposing the burial of foetuses in cemeteries.

Meloni, who has given talks to the US Christian right, considers herself a family values candidate, which is somewhat at odds with the fact that she is the daughter of a single parent after her father left and an unmarried parent herself. The same goes for Salvini, a divorced Roman Catholic who has a child outside marriage. But this is how the populists tend to roll.

If she judges it right, Meloni could well get away with her bizarre balancing act. But it is not certain how far her policies can reshape Italy. “I don’t think Meloni will ever have the impact of a Bolsanaro or Orban or even Erdogan,” Galietti said. In his view, while the “Polish outcome is not unthinkable” regarding efforts to declare Italian law above EU laws, Italy is a milder country than Poland and may not stand for it.

If she tries to make big changes to the anfi-fascist constitution, or change the presidency – currently a strong foil to errant governments – to an elected system that disenfranchises MPs, analysts say she may not last long.

Meloni will be confronted by an inbox from hell, including an economy that is struggling with the fallout of Covid. On top of this are reforming EU recovery funding, the energy crisis, and a disaffected electorate.

But the most difficult hurdle might come right at the start. Italian political honeymoons are short, and Meloni’s alliance partner, Salvini, is an expert at destroying them. He twice brought down the government he was in – most recently the Draghi unity government, when he took advantage of a row to trigger a confidence vote.

Salvini is on a steep dive from his 30% popularity of only a few years ago. His career is all about humiliation now and he might struggle to scrape even 10% this time, as his voters have switched to the more competent-looking Meloni. He would not hesitate to keep her out of the top job, in a last ditch effort to salvage his career.

“They can smile at each other and the camera,” said Albertazzi, the politics professor from Surrey University. “But Meloni is poison for Salvini.”

Berlusconi is also unreliable. He joined Salvini in bringing Draghi down. He is lucky to still be relevant, but he could still cause mischief for Meloni, who used to work for him, but left his government as it collapsed amid corruption allegations.Squabbling has brought down many an Italian government, and is holding back the left wing now. The right hasn’t governed for over a decade, so is more eager to stick to its alliance for longer. But it won’t hold forever. Italy could fall out of love with Meloni. And as the Süddeutsche Zeitung put it recently, the career of the populist politician can be “as fleeting as a fart.”