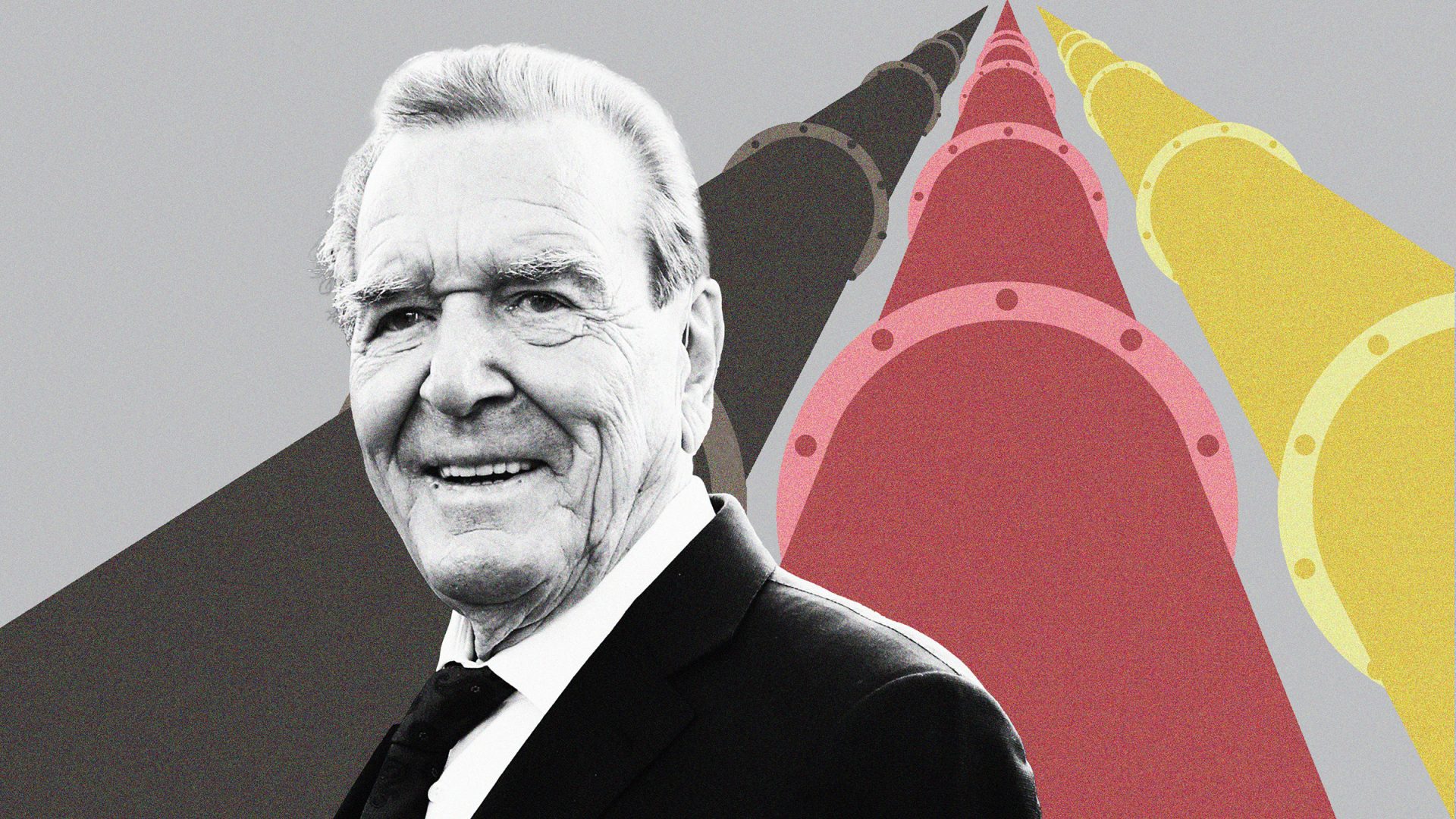

Respect the elders, the saying goes – as old age usually brings wisdom and moral guidance. The bible even commands it: “Honour the presence of an old man” (Leviticus 19:32). But what if the old man in question is Gerhard Schröder?

The 81-year-old former chancellor was due to appear before a parliamentary inquiry in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern over his role in the Nord Stream 2 saga. But it doesn’t look as if he will be grilled – respectfully – any time soon.

Schröder has already cancelled his testimony twice, citing burnout.

Let’s rewind a bit. Nord Stream 2 – the twin pipeline to Nordstream 1, between Germany’s Baltic Sea coast and Russia – was the £8.5bn project heavily criticised by Poland, the Baltics, Ukraine and the US (to name only a few). German, Austrian, French and Dutch-British companies cooperated to build it, but ownership was 100% Russky, via Gazprom. Due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine it never went into operation, and several mysterious explosions have since blown up one of the lines. It lies shattered at the bottom of the sea, a fancy playground for cod.

There’s more to it, though, which makes you think of a Banana- rather than a Bundesrepublik. Before 2022, the US had already slapped sanctions on companies involved, warning that Nordstream 2 would give the Kremlin dangerous leverage. Berlin didn’t listen. And in the north-east, the SPD-CDU government of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern – a beautiful but perennially broke bit of the country – was keen on a slice of the action.

So, in a stroke of genius, a philanthropic climate foundation was set up. Yes, really. The “Stiftung Klima- und Umweltschutz” was established in early 2021, when the pipeline was nearly complete, to help finish it. The trick was this: companies could work with the (commercial arm of the) foundation, conveniently outside the reach of US sanctions, not with Nord Stream 2 AG, aka Gazprom.

The Klimastiftung was bankrolled almost entirely by Nord Stream, with the state chucking in just a few coins of the roughly £17m capital to make it look official.

Now, the state parliament is trying to find out who came up with this clever little workaround and whether Russia influenced political decisions.

Enter Schröder. Or rather – not. The ex-chancellor is still chair of Nord Stream 2’s board, despite the pipeline being as useful as a chocolate teapot. He was invited to testify before the committee twice. Both times he bailed for mental health reasons.

In a recent letter to the committee, he said it was by no means certain recovery could “be achieved this year”. Until then, he should avoid stressful situations, “especially those that last for more than an hour and during which not everyone involved can take my health situation into consideration”.

Coincidentally, he seemed perfectly cheerful just last week when attending a parliamentary session in Hanover to watch the election of the new Ministerpräsident of Lower Saxony. While further north, in Schwerin, MPs are waiting in vain for the former chancellor’s appearance.

Well, Schröder has long been known for his subtle middle-finger attitude, which is why his letter also states that he, Schröder, was right all along. To be competitive, he wrote, Germany’s industry needs cheap energy, and as renewables are still not reliably available 24/7 and nuclear is off the table, “I am in favour of natural gas and a pipeline is more environmentally friendly than a tanker powered by heavy fuel oil that brings us LNG gas,” he writes.

Mecklenburg’s Green Party MPs are now demanding a medical certificate from a public health officer. As if someone who has no scruples and calls Vladimir Putin a friend would have trouble coming up with any attestation needed…

But that isn’t saying Schröder has no burnout. According to Bild, his bank – the Sparkasse Hannover – has blocked transfers suspected of being Russian, fearing US sanctions. Since mid-2024, he has allegedly missed out on around half a million euros. Nord Stream 2 had been paying him €200,000 every six months – for what, exactly, is anyone’s guess – but now the money is sent back to Gazprombank in Luxembourg.

Interestingly, last June, Hanover’s Green Party mayor joined the Sparkasse board. He had wanted to strip Schröder of his honorary citizenship, but Gerhard beat him to it and handed it back himself.

So here he is: snubbed at home, his Berlin office taken from him, unpaid by Moscow, with even the local savings bank giving him the cold shoulder. If that doesn’t cause burnout, what does?