Every generation needs its heroes. Military leaders, explorers, politicians. Mostly men and men of action at that. A few poets and writers are allowed to perch on a plinth. The occasional sporting hero. In fact, David Beckham was suggested as an appropriate candidate for the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square.

From ancient Egypt, the Mayans, Greeks and Romans, statues, monuments, stelae and triumphal arches have been raised for the populace to admire. The Victorians could hardly see a street corner or some public edifice without sticking up a memorial to a national hero or local worthy.

There they stood for decades, invariably unchallenged, until now when there is hardly a statue in the western world that is not under scrutiny. Pull down and destroy those with a shameful past? Hide away in a museum basement? Leave upright – with a note of explanation tacked to its plinth?

Boris Johnson insisted that removing statues of controversial figures was to lie about our history after the statue of Winston Churchill on Parliament Square was daubed by Black Lives Matters protesters but historian David Olusoga, on the other hand, argues that it is “palpable nonsense” to say that their removal somehow impoverishes history. Indeed, failure to get rid of them is a validation of people who did “terrible things”.

Sometimes it’s an easy decision. No one would defend the obliteration of all traces to do with Jimmy Savile. But when activists vandalised the statue Prospero and Ariel by paedophile and dog lover Eric Gill which stands outside Broadcasting House, the BBC did not agree it should be removed, with some art critics arguing that Gill’s artistic genius trumps his failings as a human.

That’s where the problem lies. Standards, morality, what is wrong and what is right, have changed so much over the centuries – and will continue to evolve – that the only person who could have a statue without fear of naming and shaming 100 years from today is the late Barry Cryer.

So what to make of it all? In Testament, a small, but congested exhibition at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art in south London, several contemporary artists are having a go.

According to the booklet that accompanies the exhibition – and helpfully tracks the works around the walls – the artists were invited to consider what is at stake in tearing down and erecting monuments. “Are they [monuments] defunct, illusory statements of permanence, continuity, and manifestations of power? Whose narratives do they preserve, and whose do they suppress? Can they still play a vital role in mediating communal grief and providing a locus for memory? Is there space for them to be re-envisioned?”

Several important names – such as Phyllida Barlow, Ryan Gander (recently made a Royal Academician), Roger Hiorns, and Turner Prize winners Jeremy Deller, Laure Prouvost, Mark Wallinger and Oscar Murillo – have contributed to the debate using sketches, installations, sculptures, paintings and films.

Do they meet the criteria set out in the exhibition guide and meet the challenge directly? Not really. But the subjects they choose and the style they use to express them are often implicitly answered in themselves.

First off; there are no statues to individuals. No personality cult here. Instead, causes and concerns are featured such as migration, racial awareness and the environment. One or two address man’s inhumanity to man and political corruption. Surprisingly, there are no references to the predicaments of the LGBT community which so preoccupies much of contemporary cultural debate.

Jay Tan’s suggestion is a giant cake. In Sojourners Settlers Sponge she celebrates the Chinese immigrants who settled in east London at the turn of the 20th century with a maquette of a cake extravagantly decked with ribbons, fake flowers, bangles and sweet wrappers. She wants to see a full-sized version in the middle of Limehouse where the first Chinatown was born.

Well, it could be fun, though any number of weight-watching protest groups will rally against such an unhealthy symbol.

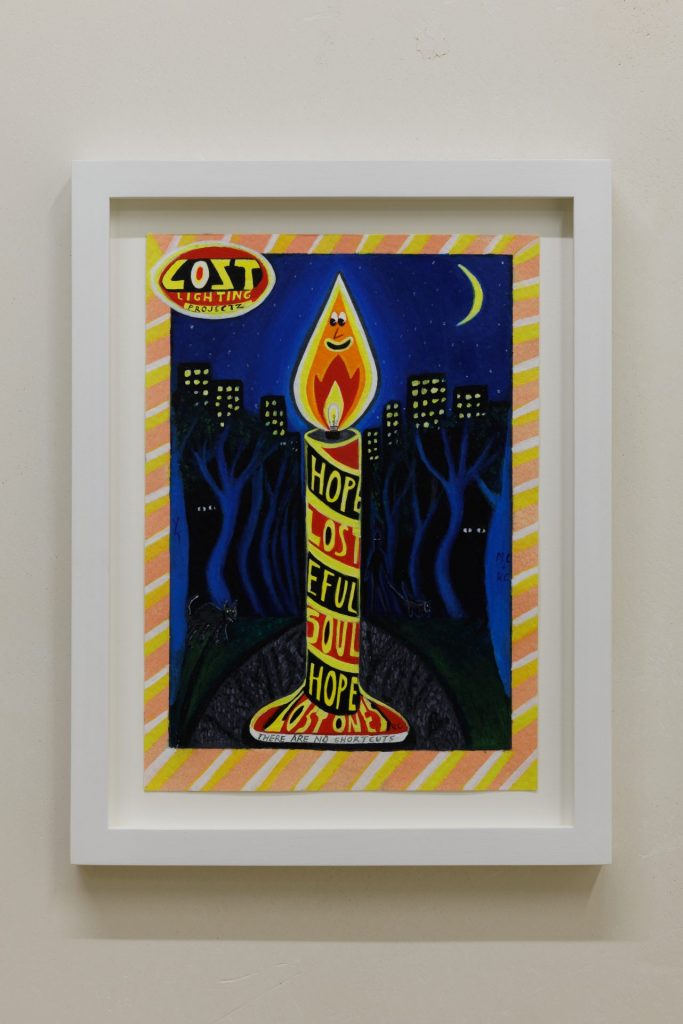

On the other hand, Rabiya Choudhry combines fun with practicality in The Lost Ones, a 14ft candle gaudily decorated with candy-coloured stripes and a beaming candle atop. She explains that it is a testament to all the people who have lost loved ones or feel lost in the world but also for women like herself who feel unsafe walking through streets at night. The lamps will guide them home.

The failings of capitalism are targeted by Tenant of Culture, aka Dutch artist Hendrickje Schimmel, who highlights the waste and poor working conditions that blight much of our consumer society. His Untitled (monument for Oxford Circus) is a proposal for a patchwork, 30 metres high by ten wide, of used trainers which he envisages being hung from a building in Oxford Circus where they will take 200 years to decompose as a mouldy, smelly, eyesore.

Rather than one symbol to aggrandise an individual Oscar Murillo has assembled plastic garden chairs, and loaded them up with lumps of bread made of corn and clay to create Collective conscience. The chairs evoke community and family gatherings, a spirit that he argues has been lost along with their working classes.

With typical look-at-me bravura Monster Chetwynd has come up with A Monument to the Unstuffy and Anti-Bureaucratic, a vast comic-cut monster with gaping teeth made of latex, foam and paper. It’s meant to be a monument to “authenticity… Radical laughter and nonsense and spontaneity.” It seemed to have worked in that respect – two children happily played in the creature’s mouth.

Ghislaine Leung has made an inflatable pub. It’s amusing but what else? Does it meet the dictionary definition of the word testament which gives the exhibition its title: Something that serves as a sign or evidence of a specified fact, event, or quality? It was created in 2021 so maybe it is a monument to all the days we couldn’t go to locked-down pubs, but does it challenge the relevance of statues as posited in the exhibition’s statement of intent?

Like Chetwynd, probably not.

What does challenge our perception and what it could or should represent is a brutal work by Phyllida Barlow – Untitled: hostage; 2022. It doesn’t seem much more than two chunks of wood supporting what looks like an upturned plastic bag.

You have to read the transcript alongside. It recalls a conversation taking place between a film-maker, Barlow and an Iranian student while they watch an horrific account of a woman being stoned for adultery in Iran. The victim is shrouded, wrapped and tied up and pushed into a hole when the crowd is commanded to stone her. By the end it is almost impossible to identify her body from that heap of mangled, bloodied rags.

Look again at the sculpture. The two pieces of wood are blood-stained stumps of legs. The plastic bag becomes a shroud to hide her battered head. A football takes the place of her head, adding a grotesque horror to the scene.

It is hard to imagine this set high on a plinth as a testament to such evil. Perhaps it should be.

While many of the offerings on display take the form of a physical entity – like the statues so loved by the Victorians – as might be expected the stone and bronze of tradition is often replaced by the video and installation of the 21st century.

Adham Faramawy has made an engaging video, A proposal for a parakeet’s garden, using the birds as symbols of migrants, often displaced by colonial forces, arriving in a country where they are not universally welcome – just like the influx of the birds in recent years which many claim is affecting the local avine population. “Wherever they fly, let them come,” runs the commentary.

Just as appealing visually, just as serious, is Scott King’s Total Floralisation (zone: 023), which argues that covering streets in flowers and plants not only helps the environment but makes hitherto rundown streets places of beauty which people would actually want to visit. But more, such efflorescence would help fight poverty as visitors are attracted to such an attractive spot, shops would flourish once again and cafes prosper.

These are understated works, pleasing to the eye and quietly forceful, which cannot be said for Dominic Watson’s strikingly vulgar work England, Their England. Made of papier maché, with added water pumps and wine, it is inspired by the satirical suggestion that each prime minister has to undergo colonic irrigation when he leaves office to purge himself of the misdemeanours committed when in power. He portrays the enema being enthusiastically expelled by the Flusher and willingly lapped up by an eager John Bull character, the Flushee.

It’s crudely funny – disgusting, in fact – but Watson is angry: “Democracy at this moment in time presents itself to us in the form of an Eton education and well-cut accent, but that’s not how it feels. It stinks. It’s rancid, it’s insidious. I want the monument to subvert that and evoke a sense of disgust.”

(He had in mind an earlier old Etonian prime minister but it’s hard to assume he would not include the present incumbent as worthy of that assessment.)

Should he want to plonk his work on a plinth, there is one to hand in the exhibition. Olu Ogunnaike has made a maquette, I’d rather stand, which is a copy of Trafalgar Square’s empty fourth plinth made of unused, rubbishy, bits of wood veneer collected from dusty factory floors and reworked to cover “one of the few monuments that are seemingly dedicated to nothing”.

Given that the other three plinths are occupied by such titans of British history as the notoriously dissolute King George IV and two Victorian generals, one who fought in the disastrous Afghan War and another who laid waste great tracts of India, this could be just the spot to dedicate to Flusher and his obliging Flushee.

Testament is showing at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art until April 3.

Richard Holledge has worked for the Telegraph, Times and Independent (among others), and writes about the visual arts for the Wall Street Journal, Gulf News, FT and New European.