One of the best literary evocations of summer comes in Philip Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings, published in 1964. Travelling by train from Hull to London on a heat-stilled Saturday, he sits us with him in the carriage, “all windows down, all cushions hot”, rattling through “the tall heat that slept for miles inland”.

It’s a journey past “short-shadowed cattle”, “blinding windscreens” and “someone running up to bowl” and as the eponymous bridal parties board along the way there’s a relaxed contentment about the journey, the quiet stillness that a hot summer’s day can invoke even on a train clacking down the eastern half of England. On a journey speckled with newlyweds there is every reason for optimism.

Sixty years on, of course, Larkin would have been tut-tutting at the “tss-tss-tss” spilling from the earbuds of a fellow traveller, listening to insincere apologies for the lack of air-con and exhaling loudly when someone takes a phone call in the quiet carriage. Larkin would absolutely have booked the quiet carriage.

That is assuming his train left at all, of course, what with rails warping in the heat and long-term underinvestment in infrastructure and staff leading to cancellations across the network, not to mention the mortgage he’d need to buy a rail ticket from Hull to London in the first place. At least he might have been able to escape into a book.

What would have constituted a Philip Larkin summer read? He enjoyed the works of Thomas Hardy, Barbara Pym and, improbably, Beatrix Potter. During the 1940s he even managed to obtain a copy of the then-banned Lady Chatterley’s Lover by DH Lawrence (“mine eyes have seen the glory of the Coming of the Lord,” he wrote to his mother) and even owned a Lawrence t-shirt in which he would mow the lawn on sunny days.

For a long train journey on a hot day, I think Larkin would probably have packed one of the 70-odd mysteries written by Gladys Mitchell, an author of detective fiction he admired very much. Sunset Over Soho sounds appropriate for the long, clanking gaps between distraction by confetti-strewn platforms.

Were he alive today, I wonder what Larkin would make of this summer’s crop of new books. I doubt he would have made any concessions to flim-flam and frippery, which seems to be the expected way with summer reading. I’ve never understood why this might be. Is it because childhood excursions to the coast were usually accompanied by comic summer specials, those bumper editions of the Beano and Dandy?

Now we’re all grown up we’re expected to make a short hop from summer specials to something similarly undemanding. If summer holiday reading is about escaping, about having more time to read away from the constant sleeve-tugging of the working week and being able to do it in relaxed surroundings, then we should just read exactly what we want.

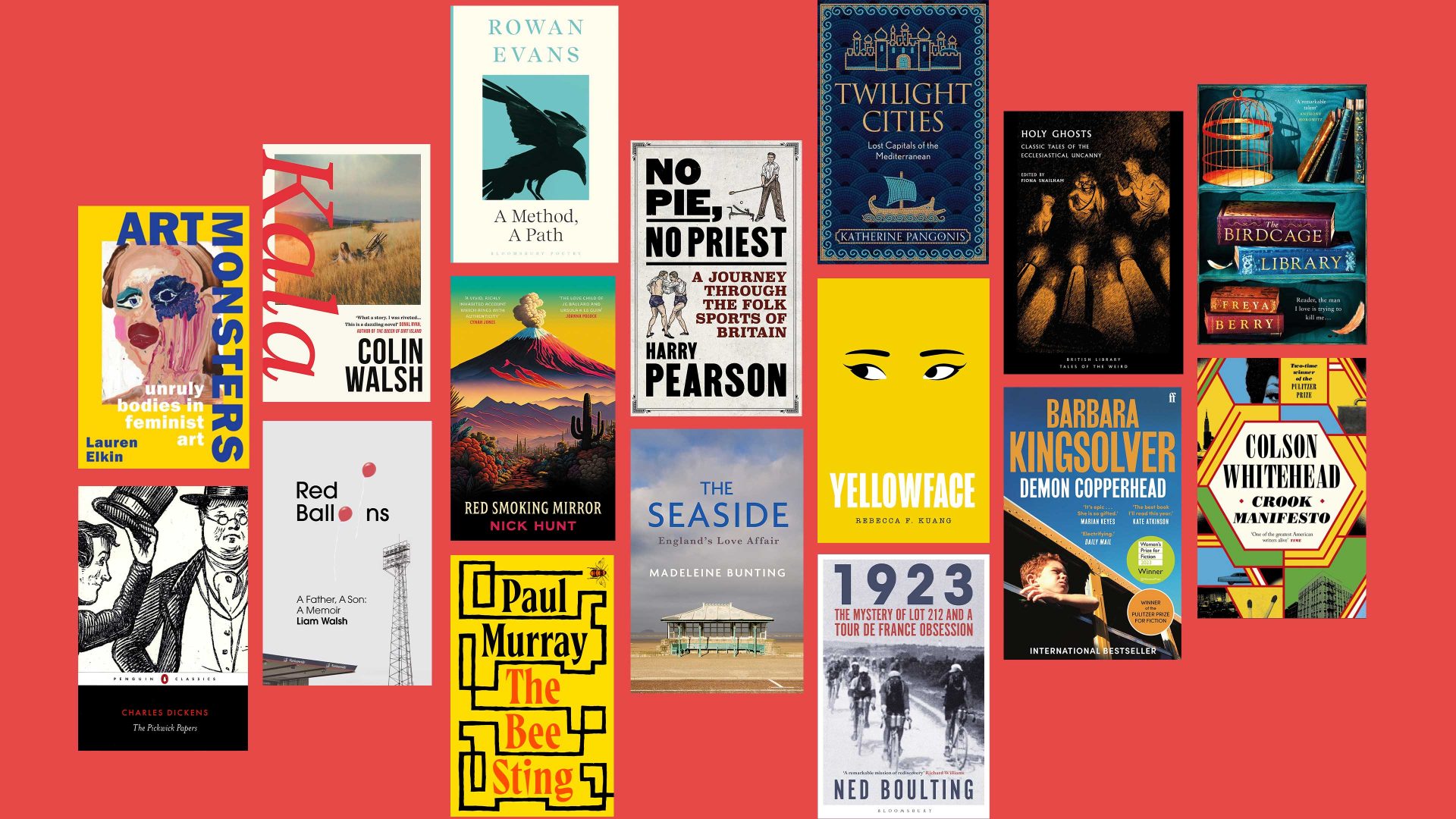

To help with this, here is a selection of titles that have caught my eye in recent weeks that might be good to fill summer days – once we’ve negotiated the Oppenheimer v Barbie conundrum at the electric music hall, of course.

One book stands out for me as particularly seasonally appropriate and is already one of my books of the year. Madeleine Bunting is the author of The Plot, a fabulous piece of micro-history and memoir about a small piece of land owned by her father on the edge of the North York Moors and Love of Country, an account of her near-lifelong relationship with the Western Isles of Scotland.

This year she has produced The Seaside: England’s Love Affair (Granta, £20), a journey clockwise around the English coast from Scarborough to Blackpool investigating the British, and particularly English, association with holidaying on the fringes of our island. In part this is a nostalgic odyssey in search of “donkey rides, Punch and Judy, the shortcomings of modest, family-run hotels, kiss-me-quick hats, lettered rock and candy floss”, but The Seaside also charts the deprivation experienced by a number of our coastal locations thanks to what Bunting identifies as “the wider national failures of a brutally inadequate welfare state, growing inequality, failing public services, and a crisis of affordable housing”.

If that doesn’t sound much like holiday fare, fear not, Bunting’s book, while justifiably angry at society’s ills, is also a magnificent piece of travel writing, combining just the right mix of history tracing our seaside resorts’ development from the 18th century, personal memoir and observational reportage.

If that’s the book I’ve swiped from the front display table of our mutual bookshop, held up to you, tapped its cover and said: “Mark my words, this is the one to save for your holidays,” there are plenty of others alongside it well worthy of your consideration.

Let’s move to the fiction section first. Nick Hunt is the author of three excellent travel narratives, including the highly original Where the Wild Winds Are, that followed the paths of Europe’s named winds and established Hunt as an excellent storyteller. Red Smoking Mirror (Swift, £14.99) is his first venture into fiction.

Novels that imagine alternative histories usually leave me cold but Hunt’s tale of South America in the early 16th century two decades after the first Europeans arrived (not Christopher Columbus but a fleet of Moorish traders from al-Andalus in a Europe where Christianity never conquered Muslim Spain) promises something quite different.

Narrated by a Jewish merchant named Eli Ben Abram, Hunt’s tale is set in 1521 Mexica, vulnerable beneath an ominously smoking volcano as a pandemic rages and news comes of a fleet of ships heading their way led by Benmassoud, an Islamic military leader with a fearsome reputation.

“Toward the end of things, one thinks about beginnings,” writes Hunt in this unusual, highly original debut novel that will hopefully not prove his only venture into fiction.

Another subgenre guaranteed to have me rolling my eyes is the novel set in the world of publishing, cliquey enough as it is without books that are one lame in-joke spread over 240 pages for the enjoyment of a few dozen people who wave to each other across lunch tables at Joe Allen’s.

One exception to this galling trend appears to be Rebecca F Kuang’s Yellowface (The Borough Press, £14.99) which is fielding plaudits from well outside the publishing bunker. It opens with two young novelists in Washington DC: Athena Liu, a wildly successful author with a freshly signed Netflix deal, and her friend Juniper Hayward, a novelist who has not met with quite the level of success she’d like.

At the end of a celebratory night, Athena chokes to death on a pandan pancake in her apartment, leaving her new manuscript about the Chinese workers sent to the Western Front during the first world war at the mercy of her friend, who steals it, makes some minor alterations and has it published as her own work.

The publishing industry does not emerge well out of Yellowface, which has much to say about the contemporary literary world and themes of cultural appropriation, but this is a rip-roaring read by an author who already has five novels to her name despite being only 27 years old. Expect Yellowface to appear near the top of many “books of the year” lists.

Now, while recommending a Russian novel might feel a little bit icky right now, trust me, this one is absolutely fine for several reasons. The Incredible Events in Women’s Cell Number 3 by Kira Yarmysh (trans. Archie Tait, Serpent’s Tail, £16.99) would be a notable enough novel under most circumstances. Set in a Moscow prison cell in the aftermath of an anti-corruption rally at which Anya has been arrested and placed in custody with five other women, the novel explores the changing relationships between the cellmates over the 10 days they are housed together.

What makes this book extra special is Yarmysh as Alexei Navalny’s long-serving press secretary. Having spent time in prison herself, not to mention being forced into exile since 2021, hers is an authoritative insider’s perspective on the perils of criticising the Putin regime. Russian literature has a long tradition of important dissenting voices and Yarmysh more than deserves her place among them.

Based on a true story, Victoria Kielland’s My Men (trans. Damian Searls, Pushkin Press, £14.99) is a deep dive into the world of Brynhild Størset, the Norwegian woman who, at the end of the 19th century, sailed for America as a teenager with a broken heart and became the young country’s first woman serial killer. She could easily have taken the salacious route in search of thrills, but Kielland handles the story with nuance and sensitivity to produce a novel that shocks and beguiles through a central character whose real-life inspiration is thought to have killed as many as 30 men.

Having thoroughly enjoyed Colson Whitehead’s last novel, Harlem Shuffle, a good, old-fashioned heist tale with a classically reluctant protagonist, his new book Crook Manifesto (Fleet, £20) catches up with Ray Carney, the Harlem furniture store owner trying hard to build a life on the straight and narrow despite his inadvertently nefarious past. This time, when his daughter asks him to buy her tickets to see the Jackson 5, Ray finds himself drawn into the orbit of a corrupt police officer with access to tickets at the elevated price of Ray’s involvement in a jewellery heist.

Double-Pulitzer winner Whitehead is one of the most prolific and versatile authors working today and this gripping, rollicking thriller still feels like he’s only getting started.

Some of the most exciting contemporary fiction of the last few years has come out of Ireland and, despite how it might look in the mainstream press, not all of it has been written by Sally Rooney. The one to watch this summer is definitely Kala by Colin Walsh (Atlantic, £16.99), already shortlisted for the Waterstones Debut Fiction Award having only been published last month.

The eponymous Kala is a young Irishwoman who disappeared in 2003 from her home village by the sea in the west of Ireland. Fifteen years later, human remains are found just as three of Kala’s gang of friends, long since moved away from the area, happen to return. Told in their three disparate viewpoints, Kala is a novel of secrets that is also a deep examination of what it means to belong; a literary thriller that promises a bright future for an author already being compared to Donna Tartt and Tana French.

Also from Ireland comes The Bee Sting by Paul Murray (Hamish Hamilton, £18.99), whose second novel Skippy Dies, published in 2010, was a huge international success. With only one book since then, Murray is not exactly churning them out, but this 650-page epic more than makes up for lost time. The Observer called him “Dublin’s answer to Jonathan Franzen” but Murray is more than that, a warmer writer and certainly a much funnier one than his US counterpart.

Switching between the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash that hit Ireland harder than most and the 1960s, The Bee Sting is a hilarious, profound family saga that turns on a single moment to produce wide-spreading ripples in time and space.

Finally, on the fiction table, regular readers might recall that I made Freya Berry’s debut The Dictator’s Wife my fiction book of last year. Hot on its heels comes The Birdcage Library (Headline, £16.99), very different in style and subject but still an outstanding novel from a writer with an exciting future.

It’s the early 1930s and Emily Blackwood is engaged to travel north and catalogue an enigmatic gentleman’s extensive collection of taxidermy ahead of an auction. This gothic-tinged mystery takes in a crumbling castle, a strange disappearance half a century earlier and a curious bundle of diary pages that turn up hidden in the plasterwork. Properly absorbing, this.

Let’s have a wander over to the non-fiction section. You might want to pick up a basket, to be honest, there are some belters here too.

A 500-page history book is a tough sell as a summer read, I’ll grant you. But if history is your thing I’m pretty sure you’ll emerge from Rachel Chrastil’s Bismarck’s War: The Franco-Prussian War and the Making of Modern Europe (Allen Lane, £30) all the better for the hours you spend with it.

Of all the many wars and skirmishes of the European 19th century, not many had the long-term impact of the Franco- Prussian war of 1870-71. Chrastil explores the background to the war, how it almost destroyed France while unifying Germany and confirming Bismarck as one of the most important figures in modern European history, as well as explaining why the war remains one of the most important events in the history of our continent – one whose repercussions are still felt today.

If you were captivated by this year’s Tour de France but are not necessarily seeking detailed accounts of bicycle mechanics and race tactics, Ned Boulting’s 1923 (Bloomsbury Sport, £18.99) might be the book for you. It’s a great example of what constitutes the best longform writing about sport – context. The finest sports books deal not just with who did what and when, but also the why, how, and what else was going on around the events on the field, court or track at the time.

1923 was an unexpected lockdown project. Boulting is a cycling writer and commentator who found himself confined to his home with little cycling to write about when, on a whim, he secured a reel of film in an online auction that turned out to be four minutes of a Tour newsreel from 1923. This prompted months of deep-dive detective work to find out what the footage showed and to place the film in the context of the times for a race passing through locations still devastated by war that enthralled a traumatised population.

This is a wonderful piece of writing that transcends sport to pass into something much more revealing about the 20th century, the legacy of a great sporting institution, the pandemic and, well, life itself.

Staying with sport, there is no finer chronicler of its context than Harry Pearson. The author of a string of books about football and cricket, notably in his native north-east, this summer heralds the publication of No Pie, No Priest: A Journey Through the Folk Sports of Britain (Simon & Schuster, £16.99), his exploration of some of the quirkier sporting endeavours to be found on these islands if one knows where to look. Taking in shinty in Scotland, the noble art of knur and spell in West Yorkshire, road bowling in Northern Ireland and the world championship of stoolball in Sussex among others, Pearson’s warmth, generosity and brilliant wit ensure his book never descends into a self-reverential gawd-aren’t-we-just-completely-bonkers odyssey or mocks those who take part. My only criticism is that it could have been longer.

Before we leave sport altogether, a quick word for Red Balloons: A Father, A Son, A Memoir by Liam Walsh (Halcyon Publishing, £13.99). In January 2020, Walsh’s 15-year-old son Patrick went to a Spurs game with his older brother and never came home, collapsing and dying in the street on his way home. Red Balloons is a heartbreaking exploration of family grief, but also a celebration of a short life and the valuable memories provided by a shared love of watching football. You might expect the message from a book like this to be how sport, in the great scheme of things, is trivial. Red Balloons will convince you that the opposite is true.

As I write, a heatwave is burning its way across southern Europe, sending temperatures soaring into the 40s while hinting at the sizzling future in store for our continent. If you are spending your summer holidays somewhere down there, well, good luck, but also you might wish to pack a copy of Twilight Cities: Lost Capitals of the Mediterranean by Katherine Pangonis (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25). It is a tour of the ancient Mediterranean, the sea named specifically by the ancients for its place at the centre of their world.

Exploring Tyre, Carthage, Syracuse, Ravenna and Antioch in vivid prose, Pangonis walks us through ancient streets and brings to life the people whose footsteps once echoed around the ancient walls, illustrating the fleeting nature of power and empire and the endurance of ancient stone. History writing at its best.

Lauren Elkin launched herself as an imaginative and authoritative voice of feminism with 2016’s Flaneuse. This summer her Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art (Chatto & Windus, £25) explores the many ways in which feminist artists have portrayed women’s bodies in their work, from the photography of Julia Margaret Cameron to Vanessa Bell’s portraits. Combining art history, philosophy, gender and incisive commentary, Art Monsters confirms Elkin as a crucial presence in modern feminist thinking.

Long-term readers might remember that when selecting my summer reads I like to look beyond titles new enough to retain that delicious inky tang on fresh paper. For one thing, most new books are hardbacks which, if you’re not using an e-reader, can be a pain in the lower back to carry around when you’re supposed to be relaxing.

When looking beyond the new I try to choose books from a few specific categories: a prize winner, a book of short stories and one of the classics, for example.

My prizewinning read this summer will be Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (Faber & Faber, £9.99), which won the Women’s Prize for Fiction this year. It is a modern retelling of Dickens’ David Copperfield transplanted to contemporary Appalachia among extreme poverty and the US opioid addiction crisis.

I have not heard anyone with a bad word to say about this book so am looking forward to it very much.

The British summer inevitably features the odd spectacular thunderstorm so I’ve selected my short story collection by anticipating darkening skies lit occasionally by lightning and soundtracked by thunder. Last month the British Library continued its Tales of the Weird series with Holy Ghosts: Classic Tales of the Ecclesiastical Uncanny edited by Fiona Snailham (British Library Publishing, £9.99), a collection of spooky tales set in religious locations. Holy Ghosts features 11 eerie stories from heavy hitters like MR James, Sheridan Le Fanu and Edith Wharton in an excellent selection drawn together with a nicely pitched introduction.

I toyed with David Copperfield as my classic, to read before tackling Demon Copperhead, but once I’d thought about Dickens I had my head turned by The Pickwick Papers (Penguin Classics, £9.99). It’s a book I used to read regularly, Dickens at his comic best. Spending part of my summer with the endlessly curious Mr Pickwick and friends sounds good to me.

Having pondered Larkin and his summer reading choices I should probably select a book of poetry with which to see out the summer too. I revisit The Whitsun Weddings regularly, but am more intrigued to delve into Rowan Evans’ debut collection A Method, A Path (Bloomsbury Poetry, £9.99), in which the poet reaches back to the earliest days of verse to explore the rhythms and metrics of old English in poems set in a range of locations from Somerset to East Anglia via Andalucía. Evans certainly sounds like a poet to watch.

Anyway, we have now looked at so many books they’re standing at the door of the bookshop jangling their keys and looking pointedly at the clock. Larkin has just hurried past the window putting on his hat on the way to the station for his return to Hull. Wherever you spend the rest of your reading summer, may it be an absorbing one in precisely the weather conditions you desire. I mean, after all, it’s been a bit of a year so far – you deserve it.