Labour says its planning reforms are “at the centre” of its vision for reinvigorating the UK’s sluggish economy. While most coverage focuses on the party’s plans around boosting housebuilding, Rachel Reeves has pledged to make planning one of its “three pillars” for the economy, and hopes it can finally boost UK productivity and economic growth.

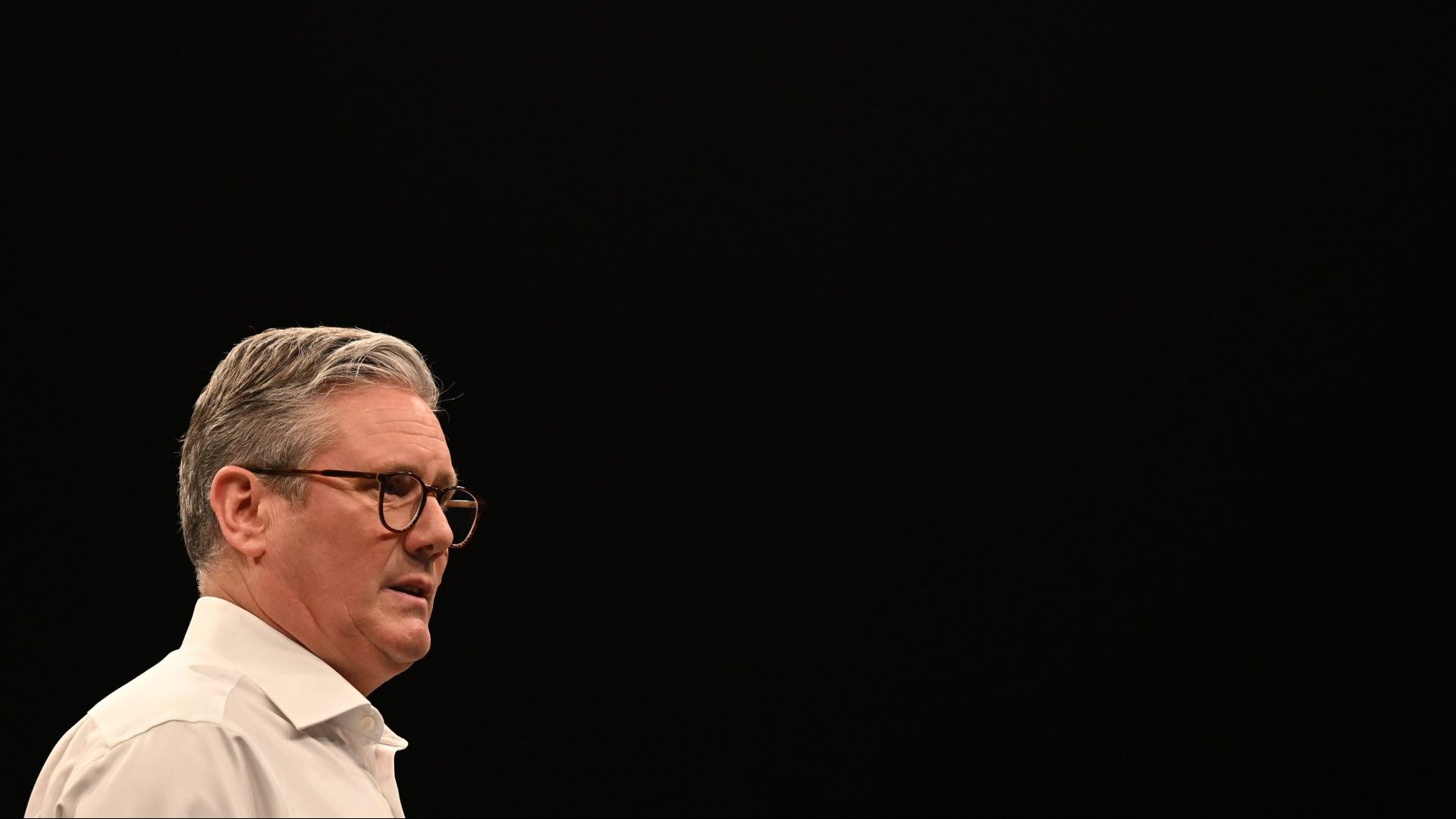

Keir Starmer has said overhauling planning was at the core of his plans to “bulldoze through barriers to British success”. Less than 500 yards from the borders of his own constituency, however, is a planning row that highlights just how entrenched some of those barriers are – and how Starmer may have to fight his own party tooth and nail to remove them.

The row is centred on one of the most well-heeled and leafy of north London’s neighbourhoods, Tufnell Park, sitting on the border of Islington and Camden, surrounded by small parks and fancy pubs.

Longstanding political nerds may also remember it as the long-time home of shadow environment secretary Ed Miliband, and thus of the infamous kitchengate row (neighbourhood sources reveal the Milibands’ second kitchen is no more).

On one side of the row are a group of local residents, backed by the local Yerbury primary school and Islington Council. On the other is Ocado, who wants to open a distribution centre in the area, which would back onto the school playground.

The Islington North constituency party (Jeremy Corbyn’s home seat) is backing the campaign against the distribution centre, and last week Islington council leader Kaya Comer-Schwarz was the guest of honour at an online “NOcado” campaign event.

On the face of it, the campaign’s concerns seem reasonable, and far from NIMBY territory – the idea of a warehouse and its accompanying delivery lorries next to a school playground is not a comfortable one. Traffic past the school entrance and exit could be an issue, air quality would surely be a concern, and it seems odd to develop industrial land in a residential area.

The objections of the council and NOcado campaign centre on asking why Ocado has not tried to apply for planning permission for the site, instead trying an expedited process that they accuse of trying to bypass democratic safeguards.

It is only when you look at the site in person (or at least on Google Maps) that you start to see why Ocado thought this might be a good spot for a warehouse. It is right next to an operational royal mail distribution office – which already has vans coming and going – which is itself on an industrial estate next to railway lines.

That site includes a repair base for Islington Council – which is helping the campaign block Ocado’s plans – as well as a Jewson’s trade supply shop, a Transport for London depot, and a car repair shop. All of these are supplied by their own road that doesn’t pass the school. A quiet and unspoilt site this very much is not.

More baffling than all of this, though, is that the existing building on the site that Ocado wants to use as a warehouse is… a warehouse.

Though it had been disused for several years at the time Ocado took on the lease for the site, it had been a BT depot – leaving it somewhat baffling as to why Ocado is being asked to obtain planning permission to use an existing warehouse for its intended process.

The Ocado site is quite a large one on the far side of an industrial estate, butted on the other side by a busy railway line – it is hard to see how such a site could be used for housing or some other purpose.

As odd as it sounds, industrial land is needed even in central London – packages have to be delivered from somewhere, vehicles need repairing, business must go on. Most such land has some form or other of protection against change of use, as the second industrial land is used for any other purpose, it is lost forever – the vacancy rate on industrial sites much lower than office space. It is in high demand.

The question is what residents and the council want to be done with the existing warehouse site. Locals and the school could be forgiven for hoping it just stays derelict – no-one within 100m of the Ocado site is likely to be looking for a job in a distribution centre or as a driver there any time soon, even if their neighbours a few hundred metres further away might be.

The council, though, surely would prefer to see the land being used usefully. And while Ocado has been accused of skullduggery around the confusing question of not seeking planning permission, it is a public-facing company with deeper pockets than others that might use the site.

Among other commitments, the company had pledged to operate only electric delivery vehicles from the area, and to build a living wildlife wall between the edge of the warehouse car park and the wall of the school playground.

This row is not a new one and it does not look set to be resolved any time soon: by June, Ocado will have paid the rent on a central London site for four years without being able to engage in any activity on that site at all. Could there be any better example of the planning system killing productivity than paying for a warehouse for four years while being banned from using it as a warehouse?

Ocado might be forgiven for wanting to give up on the whole thing and walk away at this point – except they can’t. The company will have agreed a lengthy lease on the site at the time it took it on, so to walk away it has to convince someone else to take on that lease.

Given that no sane company would take on a warehouse it wasn’t allowed to use, Ocado is forced to fight round after round against Islington’s council, its local party, and the directly affected residents’ campaign group – for a site it might not even still want to open.

This is a story that is repeated right across the country: the only thing special about this example is its location, right on Keir Starmer’s doorstep.

Labour headquarters is talking a good game on planning and its constrictor-like grasp on British productivity. Talk, though, is cheap – and it’s clear that the new line from HQ hasn’t got all that far in the party. Will Labour’s plans to change the planning system get caught up in the same administrative hell as every other project?