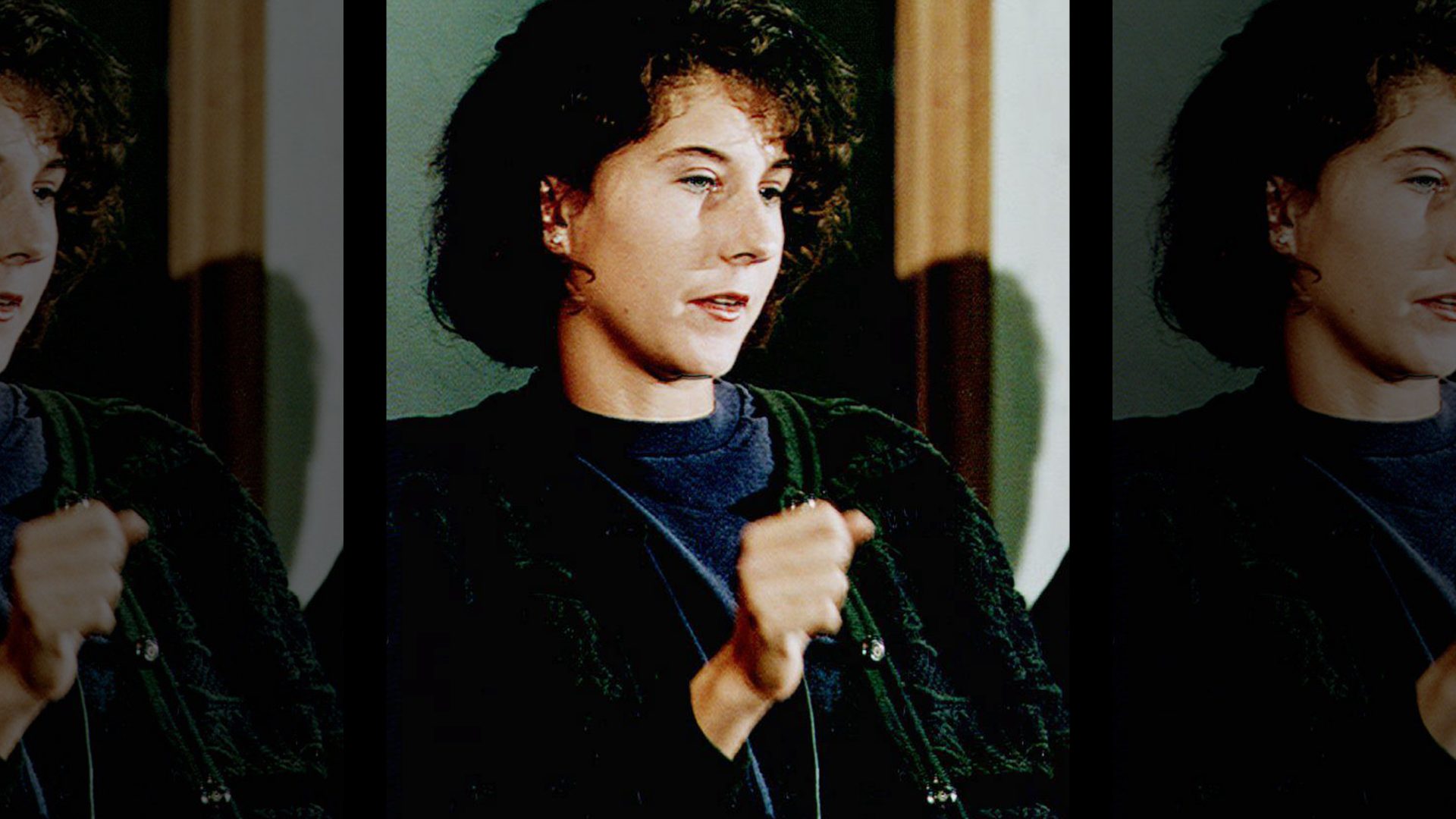

In 1993, Monica Seles had the world at her feet. The 19-year-old had spent 108 of the previous 112 weeks as the women’s No 1 ranked tennis player. She’d won seven of the previous nine Grand Slam tournaments, finishing runner-up in an eighth (she didn’t compete in the other one). In short, she had been imperious. Then in an instant, all that changed.

On April 30, she was playing Magdalena Maleeva in the Citizen Cup in Hamburg, a routine warm-up event ahead of the clay-court season. As the umpire called time on a drinks break, Seles felt a sharp pain in her back. She screamed, stood up and, grimacing, reached over her shoulder, then staggered backwards and collapsed into the arms of a tournament official.

She had been stabbed. Her assailant, Günter Parche, a 38-year-old unemployed East German, was obsessed with her keenest rival, Steffi Graf. He leaned from the stands and knifed her once between the shoulder blades with a nine-inch serrated boning knife. Before he could stab Seles a second time, he was wrestled to the ground.

“The ripple effects were huge,” said Christopher Clarey, who has covered tennis for the New York Times since the 1990s. “Security immediately became a much bigger deal at tournaments. Players had security posted behind their chairs, as they still do to this day. It gave everyone in the game, especially in the women’s game, a sense of insecurity.”

Had the wound been a centimetre to the right, Seles would have been paralysed. Instead, miraculously, because she leant forward at the exact moment Parche lunged at her, the blade only penetrated one and a quarter inches deep, just missing her spinal cord, lungs, and other vital organs.

Although the physical damage healed in a few months, the mental wounds lasted considerably longer. “I was plunged into a fog of darkness and depression that I couldn’t see my way out of,” Seles wrote in her autobiography.

Plagued by nightmares and flashbacks, she entered a period of self-imposed seclusion, only returning to competitive tennis 28 months later, by which time she had missed 10 Grand Slam tournaments. Understandably, she was not the dominant player she had been. As Martina Navratilova lamented, the attack had “changed the course of tennis history”.

Perhaps because of the passage of time, perhaps because Seles was never able to fulfil her potential, her impact on the game is easily forgotten. “It was kind of a revelation to watch her play,” says Steve Flink, the former editor of World Tennis Magazine, who was inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame in 2017. “She was almost transcendent because we’d never seen anything like this. For one thing she was left-handed, and for another she used two-handed strokes on both sides, not just the backhand. It meant she got incredible angles with her shots, as well as depth. It was an unbeatable combination.”

This technique, although rarely directly replicated, helped to usher in the era of power players in the women’s game. It was the reason why Serena Williams – who along with her sister, Venus, took it to another level – named Seles as her favourite player.

This game-changing, on-court style was matched with an unshakeable confidence and ruthlessness. “I’ve covered many sports in my career,” said Clarey, “and Monica is one of the greatest in-the-moment competitors that I’ve seen, without a doubt. I’d put her up there with Michael Jordan. She had relentless mental strength and a point-by-point, moment-by-moment focus. She’d reboot the computer each time and play the next point with the same ferocity.”

Yet this was not accompanied by either nastiness or arrogance. Off-court, Seles had a bubbly, effervescent personality and was prone to regular fits of giggles. (Sportswriter Bruce Jenkins compared her to a “giddy teenager at her first wedding reception on her third glass of champagne”.) However, the supposedly “unladylike” grunt that accompanied her intense on-court effort became a cause célèbre, particularly in the prim environs of the All-England Tennis Club. The Sun labelled them “disgusting” and set up a “gruntometer”, measuring her shrieks at 82 decibels, “as loud as a diesel train”.

Wimbledon, where the low bounce of the grass courts was unsuited to Seles’s game, was the one Grand Slam title she did not win. Only once did she progress beyond the quarter-finals, in 1992 when she lost in straight sets to Graf in the final. In 2022, when Centre Court celebrated its centenary with a parade of former champions, Seles was absent. As such, in Britain, with its myopic focus on the events at SW19, she strikes a forgotten figure.

But, given her dominance, that shouldn’t be the case. Between January 1991 and April 1993, Seles reached the final of 33 of the 34 tournaments she entered, winning 22. Along the way, she compiled a win-loss record of 159-12 (a 92.9% win ratio), which included a 55-1 win-loss record (98%) in Grand Slam tournaments.

“If it hadn’t been for the tragedy, she would have won many more majors,” says Flink. “We’ll never know how many, but she was on her way to some astonishing numbers at the majors. She had a big four or five years ahead of her, had that not occurred.”

The only person with a comparable record was Graf, who won six Grand Slams before she turned 20, and another two before she turned 21. If anything, this only reinforces the impressive nature of Seles’s early success. She won her titles during a period when Graf was at her peak.

This was Parche’s motivation; he wanted his compatriot Steffi Graf to regain the No 1 slot, and he saw Seles as the key impediment. With Seles out of contention, Graf quickly regained the top spot, where she stayed for 87 weeks. She won the four Grand Slam tournaments immediately after Seles was stabbed and another two during the period of the player’s enforced absence. Parche had got what he wanted.

Seles also lost out financially. Endorsement deals she was about to sign were cancelled. She unsuccessfully sued the German Tennis Federation for lack of security and lost income. Her recovery was further hindered by the court case. Despite Parche admitting that the attack was premeditated, an attempted murder charge was dismissed, and he was only charged with grievous bodily harm. He was not jailed, instead receiving only a two-year suspended sentence. Nineteen months later, an appeal judge upheld the verdict, citing Seles’s unwillingness to testify as partial justification. Seles refused to play in Germany again.

Diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, Seles slumped into a deep depression, compounded by her father Karolj’s cancer diagnosis (he died in 1998). She began bingeing on chocolate pretzels, crisps, Pop-Tarts and ice cream. She struggled with her weight, and the impact it had on her movement and timing, throughout the rest of her career.

More than that, the attack had robbed Seles of her safe space. “Tennis never did anything bad to me,” she reflected later. “The tennis court was my place. Anything that was happening in my private life, I could forget about it and think of the ball. I felt the safest there. All my worries were gone. I didn’t have to think about anything when I was there. Suddenly, that was taken away.

“I was for so long in such a dark place. So unhappy. I thought there was no way up, I didn’t know how to go up. I felt I was in a deep hole and getting deeper. My dad told me: ‘Maybe you need professional help.’ I had a very hard time talking about it. I couldn’t keep from crying. But I felt I was doing the right thing because I was going deeper and deeper, down and down.

“I didn’t know how to get out. I didn’t think there was a way out. If I hadn’t done that, gone to a psychologist, it would have been bye-bye, Monica.”

Parche, who died last year, not only robbed Seles of her best years, and possibly the chance to become the greatest player of all time, but he also robbed the game of what would have been one of the sport’s greatest rivalries, between Seles and Graf. Their 1992 French Open final was a game for the ages, Seles eventually winning 6-2, 3-6, 10-8 after a gruelling 91-minute final set. Barely a month later, Graf romped to a relatively easy two-set win in the Wimbledon final. Then, at the start of the following year, Seles came from a set down to beat Graf in the Australian Open final.

“That has unfortunately been one of the big holes in the women’s game in the last 20 to 25 years,” says Clarey. “There really hasn’t been a transcendent rivalry. That’s really hurt the women’s game in terms of its broader appeal; the men’s game has had much more of that.”

In a testament to her mental fortitude, Seles reached the final of the first Grand Slam tournament she contested after her comeback, the US Open in September 1995, which she lost to Graf. She then won the second, the Australian Open in January 1996, against Anke Huber, before also losing the 1996 US Open Final, again to Graf.

“I think others would not have come back at all, certainly not to the top five, top 10 levels,” says Flink. “But the same ferocity was not there, she was as professional as she’d always been, but there was just something missing.”

Seles retired in 2008, although she had not played a tour match for five years, following a foot injury in the spring of 2003. In effect, therefore, her career ended when she was 29, but it was always overshadowed by that one moment a decade earlier.

“I can’t say whatever was meant to be, was meant to be,” Seles told the Chicago Tribune in 2004. “When I look back, I’m sure my career, in terms of achievement, would’ve been different if I hadn’t been stabbed, and I’ll always wonder why I’m the only one in history who that ever happened to.”