Parliamentarians are not like the rest of us. You have to be something of a strange breed to want to be an MP in the first place – the job is a seven-day-a-week one, gladhanding locals for votes one minute, managing constituency issues another (with an office of in-effect under-qualified social workers doing casework), and then spending long hours traipsing through voting lobbies to keep the wheels of government turning.

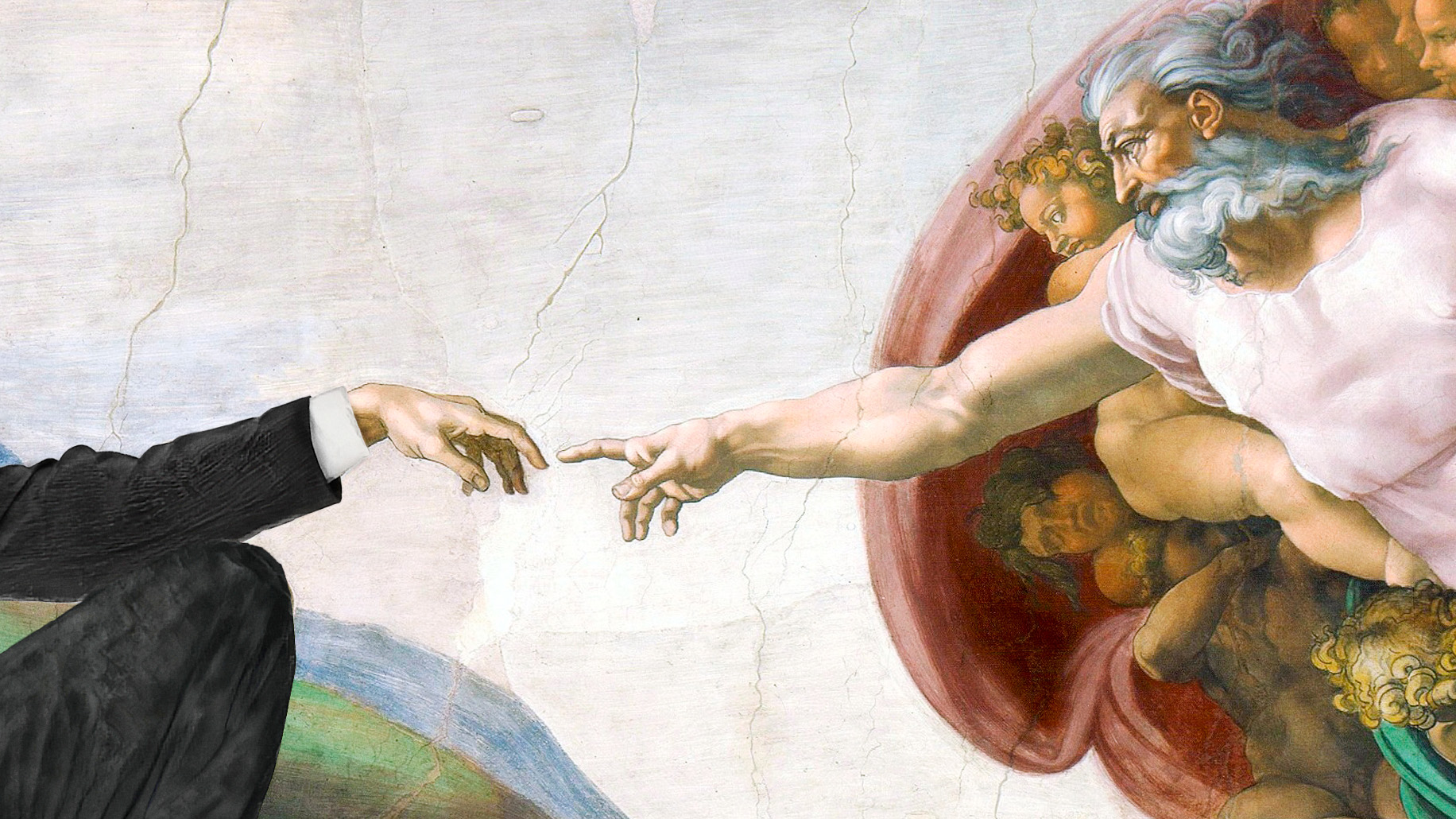

All of that is in the often vain hope of one day becoming a minister senior enough to actually be able to influence policy in the direction you would like it to be steered. Given the long odds against and the years of work with no guarantee of success, it’s perhaps not a surprise that one of the big ways in which politicians differ from the rest of us is faith.

The UK is an increasingly secular country – there is no longer a Christian majority in the UK, though it remains by far the largest religious denomination (those with no faith come second, Muslims are a distant third).

But British politics is dominated by those of unusual faith – Tony Blair was a committed Christian who was famously advised by someone familiar to TNE readers that “We don’t do God”, and while it was less noted at the time, David Cameron described himself as an “evangelical” Christian. Theresa May is a regular churchgoer – unlike 95% of the English population – and Rishi Sunak has also spoken of being motivated by his devout Hindu faith.

From our prime ministers down, religion appears to play a bigger part in the lives of our politicians than it does for most of the public, which affects the nature of public debates in ways large and small. In a country where around 37% of people identify as having no religion, just 150 MPs (23% of the total) took their oaths of office without a bible or other religious text.

Religion is baked into the very nature of proceedings in the chamber, perhaps unsurprisingly, given that the UK is still officially a nation unified with one of its churches. The start of each day in the Commons begins with Anglican prayers – but thanks to the anachronistic nature of Commons rules, MPs of others faiths (or none) are required to attend those prayers if they wish to reserve a seat for the day, a quirk that has thus far resisted all modernisation drives.

The intermingling of religion and public life is even more apparent in the Lords, where the bishops of the Church of England have an allocation of 26 seats and their own special designation as Lords Spiritual, as opposed to “regular” peers, who are the Lords Temporal. In a pluralistic country in which a majority of the people do not identify as religious – let alone as regular churchgoers – this level of influence begins to feel not so much anachronistic as outmoded.

But it’s on substantive matters of debate that faith has the most obvious influence – quite a few matters in the Commons are reserved as “matters of conscience” and are by tradition not whipped, meaning that even if a government is trying to pass a particular policy, it will not punish The dangers of doing God ministers or MPs who vote in a different direction.

This isn’t intrinsically a problem, though it does merit a pause – MPs are not given this discretion if they are being asked to vote on legislation to make the benefits system more punitive, or to renew the nuclear deterrent, or any number of other decisions that would trouble many consciences in one direction or another. Instead, these “votes of conscience” are generally reserved for two issues – abortion and issues around LGBT rights. Why are these issues alone given a moral carveout when so many others are not? Is there really a working justification for this limited exception?

There is a subtler influence at play with religion’s role in British politics, too – such as on the issue of assisted dying. The British public overwhelmingly supports changing the law to make it legal for doctors to assist in the suicide of people with terminal illnesses, should they wish for it and require that help.

It is one of few issues that cross party lines: 74% of Conservative voters support this change, and 76% of Labour voters agree. On the more contentious issue of assisted suicide for incurable but non-terminal conditions, public opinion is more divided, but still leans in favour of a change in the law.

However, MPs feel very differently from their constituents on this issue, and have persistently resisted change – only 35% back doctor-assisted suicides for people with terminal illnesses, and successive governments have largely avoided bringing the measure to the chamber. Campaigners have expressed frustration that it is religion – and the desire to avoid clashes along faith lines – that has fed into this caution.

Faith also provides a useful network for the politically ambitious – and while UK religions often avoid the ostentatious lobbying of their US counterparts, they have proven effective at helping to propel those with faith into the Commons. Christian groups run internships (often including funding salaries) into the offices of Christian MPs, building a network of researchers, some of whom then go on to climb the ranks.

Senior ministers in influential roles have affiliations to often interesting subsets of Christianity: Michelle Donelan, who as the secretary of state for the new government department overseeing science and innovation is now the minister in charge of the UK’s burgeoning biosciences industry, for example.

Donelan’s husband was once connected to the Plymouth Brethren, a smallish Christian group that usually discourages marrying “out” of the faith, leading some to privately wonder if that group will hold any sway on her future decision-making, especially as companies connected to the group appeared to benefit from government PPE contracts – though there are no specific allegations of wrongdoing against Donelan herself.

Faith is clearly a personal matter and something that can be a great source of public good – if it drives people to work genuinely to improve the country and its services, without seeking to impose its own values on others, it can clearly be welcomed by even the most hardened of atheists.

But everything is worth examination, and so too we should think about the role of faith in a nation that is becoming not just more multicultural, but also more secular – if the UK is not a Christian country, for how long can its institutions formally incorporate that faith?

For the sake of public policy, fairness, and open access to the institutions of power, we do need to talk about God – and how far He should have the final say in our temporal governance.