A city, like a person, has its beating heart, the ever-changing sensory lived experience of its citizens. It has its public face, how it greets the world. Cities, like people, are also encumbered by others’ projections. Some are easily shrugged off. The most resonant are absorbed, enter the city’s pulse, grow into its face. I think of Berlin: Sally Bowles and Isherwood. I think of Dublin: Sally Rooney’s Trinity lovers.

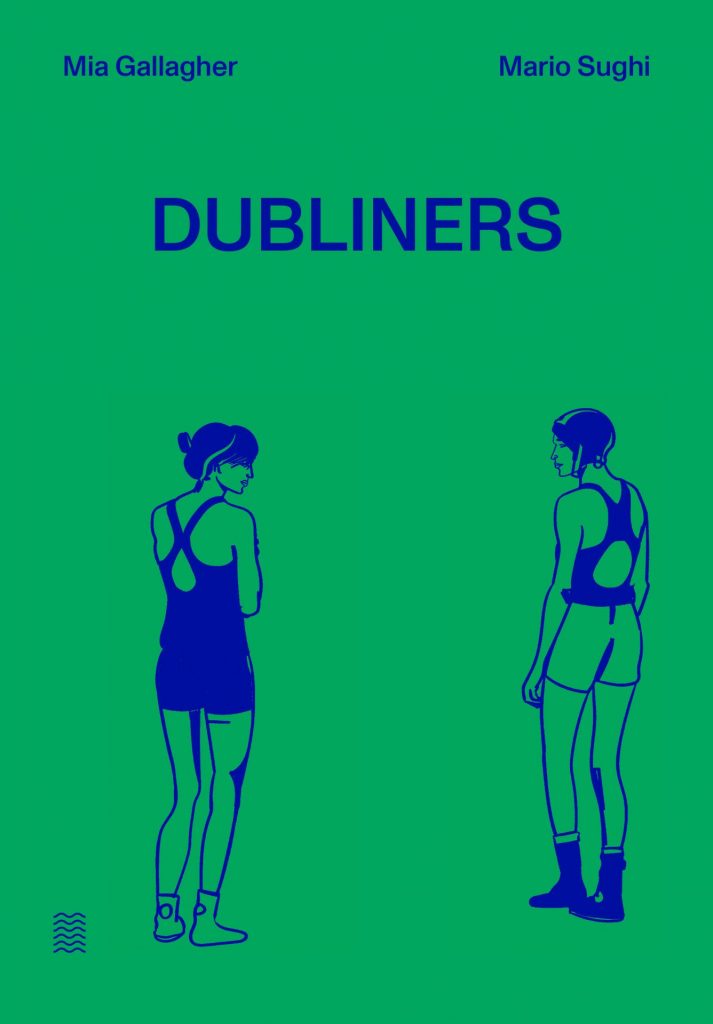

Last November, the visual artist Mario Sughi, who illustrates the jackets of Rooney’s Italian translations, approached me to make a book. Published to coincide with a show of his work at the Italian Institute in Dublin, it would be titled, like the show, Dubliners. Mario didn’t want me to write anything new for it. His concept was a montage of already-made images and texts, which would crash into each other to create a story of Dublin and its people. By existing, that story has become part of a larger conversation, the intersecting dialectics shaping how Dublin sees itself – and is seen – as a city and contemporary European capital.

Cities are tidal, eroded and augmented by the re-attribution of value, the seizing, withholding and granting of resources. They can begin almost accidentally. A Viking sees a river on a sheltered bay, with a clear view of enemies coming from the east, thinks: let’s push out the Gaels – and there’s Dublin.

Dublin’s narrative, like that of its sister European capitals, has been profoundly influenced by migrants. Some – the Vikings – came to conquer;

others, like Mario Sughi, born in Cesena on the Adriatic coast, or my own parents, from the Irish port town of Waterford, were drawn by work or study. Viking settlement, regional Norman power-base, major city of the British empire. By the 18th century, Dublin was cosmopolitan and prosperous – buzzing with the English gentry who had appropriated vast tracts of Irish land, the Quaker merchants grown rich on chocolate, sugar and coffee leached from Britain’s other colonies, often on the back of slavery. Their Dublin – gracious Georgian architecture, Handel’s Messiah – is still embedded in the city’s public face. There’s even a glimpse in our book.

In 1801, after the United Irishmen’s failed rebellion, the Irish parliament notoriously voted itself out of existence. Power, and the landlords, sucked back to England. Dublin became a backwater, enduring almost 200 years of colonial and post-colonial stagnation before re-emerging as a poster child for global neoliberalism during the 1990s boom, when Mario Sughi and I first met.

To what extent is Dublin’s story typically European? National capitals are precarious things. Berlin became Germany’s only because of Prussia’s might. Toss a coin and it could have been Bavaria’s Munich or the proudly independent city-state of Hamburg. After Versailles, when Weimar was

anointed top dog, Berlin – unlike sad post-Act-of-Union Dublin – continued

to dazzle, attracting and enhanced by incomers. Isherwood, Kirchner, Brecht, Lang, Brooks… The Nazis, who understood glamour, reinstated

Berlin; the allies carved it up, making dull Bonn the federal seat. But Europe

and its nations are constructs of imagination as much as geography and the cold war’s end needed more symbolic oomph. Back strode Berlin, its battle scars only adding to its mystique.

Would Paris occupy such political centrality if the Cathars had kept power in Occitania? Would Madrid, if Philip II hadn’t been lured back from Valladolid by cheap real estate? As for Dublin – without the Norman invasion, would Tara, seat of the Gaelic High Kings, be Ireland’s capital now? Would Derry, if the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell had repelled the Tudors? Without the Easter Rising, the War of Independence, the Treaty, partition, would it be – gasp – Belfast, first to industrialise and nearest geophysically to Britain? Or would it be Cork, Ireland’s Hamburg, self-appointed “real capital” and the Irish city closest, as the crow flies, to continental Europe?

Here, I think, is the rub. Ireland is an island, perched on Europe’s westernmost edge. The geography makes for a complex connectedness. Part of, but distanced; outside, but in. Most people identifying as white Irish have “European” ancestry. Norman, Angle, Saxon, Viking. Earlier still, the

continental Neolithic farmers who came to Britain and Ireland across the North Sea via the diminishing Dogger Bank.

My own paternal grandmother, whose mother was a printmaker, was German, born in Berlin with Polish and Hungarian antecedents. Whenever I visit mainland Europe, I feel a rush of connection. But like most Irish people, I still talk of going “to Europe” in a way that Berliners, or Romans, don’t. We usually mean the continental landmass, not the geopolitical entity, but it’s an

interesting phrase. Are we not “real” Europeans? Maybe other islandey countries on the edge feel the same. Greece, for example. But isn’t Athens on the mainland – and Europe’s “cradle of civilisation” besides?

The neighbour complicates things further. From a continental perspective, Ireland lies beyond Britain. From an island perspective, Britain lies between us and the continent. When we were all in the EU, it was less of an issue. But

after Brexit’s sun came out to light the uplands, our filters went dark again. Ireland, we told ourselves, never felt more European, but, looking east from

Dublin, the Irish city closest to England, all I could see was the other island. As a symbol of our shadowy outsidey-in-ness, it’s hard to find a more resonant moment than that 2019 Cheshire pow-wow between Boris Johnson, former mayor of London, and Leo Varadkar, a second-generation Dub like myself. No Brussels in that garden.

Colonised, precarious, peripheral, occluded: these dynamics shaped Dublin’s stories. Add in another: abandoned. Ireland is famous for exporting its people. The medieval monks who set up the misnamed Schottenkirche across central Europe. The mercenaries who served in countless wars on European battlefields. The failed revolutionaries festering in Rome and Paris. The convicts deported to the New World. My peers who worked Grenoble fruit farms in the 1980s, and those who designed code in Frankfurt in the 1990s.

Emigration is a vampire, sucking life from a city’s pulse. I don’t know if Dublin can claim more net emigrants than any other European city, especially today. But growing up in the 1970s and 80s, it felt like it. Most Irish books I read as a child hardly featured Dublin. Films, made by Americans or Brits, focused on the bog, the North, the priests, the past. In school, my city came in shards, crafted by men, mainly dead. Of course I read the great writers whose Dublins dominated how the capital was seen in the collective European imagination. But they’d all left, too.

Mario Sughi’s title choice isn’t an accidental nod to James Joyce, whose 1914 Dubliners is acknowledged as a bar-setter for the European and global north short-story form. By appropriating Joyce’s title, Mario was throwing down a gauntlet, and by accepting his invitation, I suppose I was, too. Our Dubliners, like Joyce’s, occupy a place somewhere between observation and fantasy. They too took time to arrive. But unlike Joyce’s Dubs, who emerged on an exile’s desk in the heart of continental Europe, our lot came to life inside the city as its fortunes turned yet again.

Mario came to Dublin in 1988, the same year I graduated from college. The smart money was still on leaving, but we chose to stay – Mario by migrating, me by not emigrating – and we haven’t left yet.

There is “Europeanness” to our book. Our ethnicity. The publishing team, based in France and Italy. The title and concept: appropriation, assemblage, collage, how Dada is that? In the glowing tans and designer shades of Mario’s people, I see Italy. I see Norway too, home of the Vikings and my great-grandmother’s mentor, Edvard Munch, in those isolated young women hurrying down empty, colour-pulsing streets. Mario operates at large, out in the city, close enough to people to capture them, far enough so they can’t tell. That’s European, too. Baudelaire’s flâneur, Catullus of Rome. But it’s also very Dublin. Zozimus, the 19th-century street-rhymer; Joyce’s Bloom. And when I look at those ageing lady swimmers, striding towards me in their tight swimsuits, sensible footwear and salty hair, I couldn’t be anywhere but home.

It’s hard to draw lines between what’s Irish, Dublin or European. Like trying to disentangle genetic code. Perhaps it’s just that art, like cities, needs to borrow to stay alive.

Now Dublin is cosmopolitan, buzzing again, its population almost doubled in the 25 years since Mario and I met. Like its sister-capitals in Europe, it’s facing challenges. The ravages of global capitalism, unease around nationalism, housing crises, poverty. I worry about the long term: climate catastrophe, wars. Is that unease in our book? I don’t know.

But my city’s pulse is still beating, its mask still shifting. And the waves of new life, whether coming from Europe’s embattled fringes or places far beyond the continent, continue to crash into its story, making space for new Dubliners and the conversations they will have.

Dubliners by Mia Gallagher and Mario Sughi is published by Marinoni Books, price €34 and is available now from marinonibooks.com and brooksidepublishingservices.com