The distinction of having your own foreign-language name-form has been a rare one in modern times but, just as Francesco Petrarca is known to English-speakers as Petrarch, and Shakespeare to Poles as Szekspir, so Konstantinos Kavafis is known in English as Constantine Cavafy.

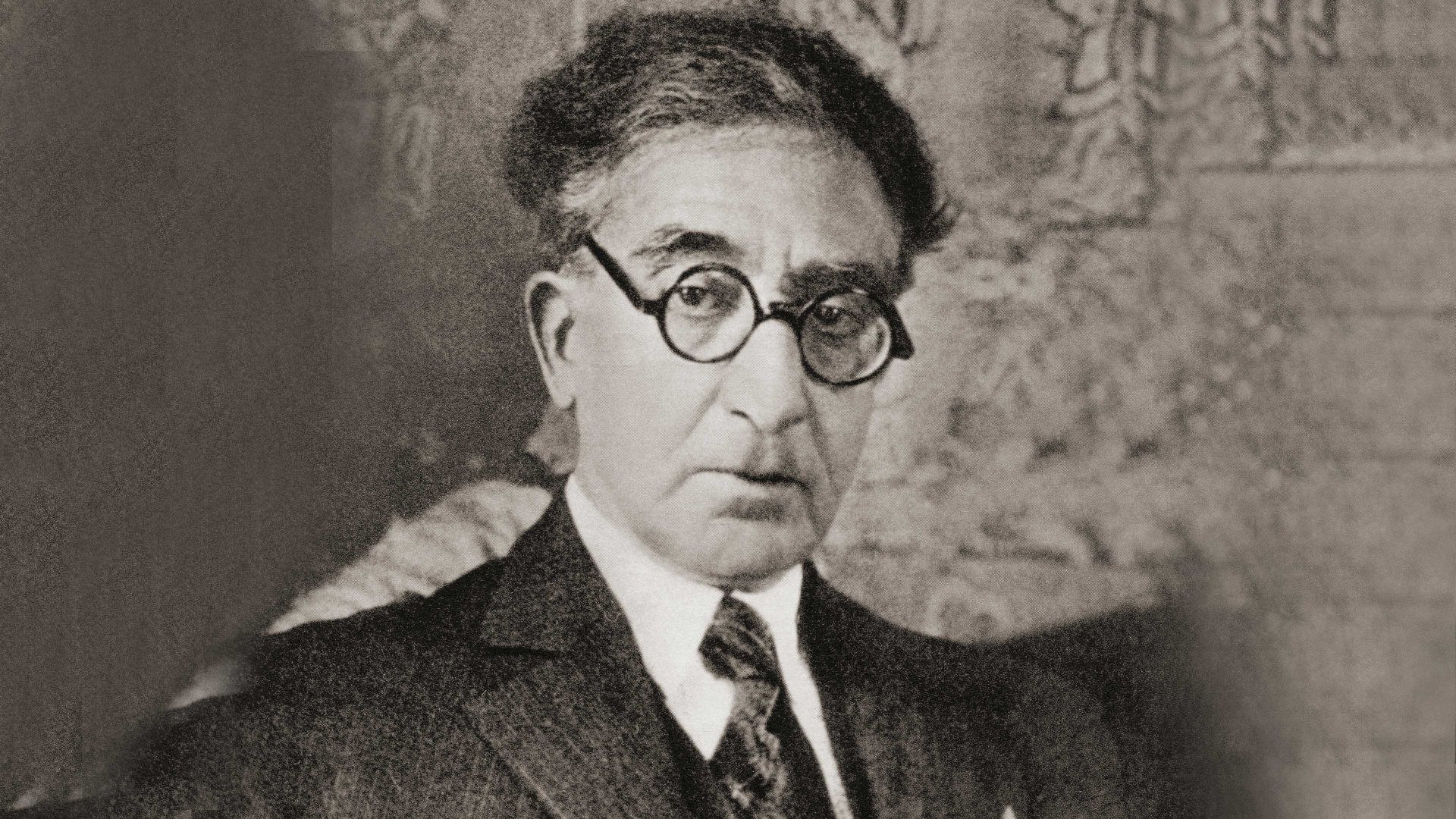

Cavafy was one of the greatest of all Modern Greek poets. He lived from 1863 to 1933, dying on his 70th birthday. But he never lived in Greece. He was born into the large Greek community of Alexandria, Egypt, and resided variously in Liverpool and Constantinople as well as Alexandria.

One of Cavafy’s best-known works is his 1904 poem Waiting for the Barbarians. The reader understands that the scene is a city-state such as Ancient Rome at the time of its decline and fall. “Why don’t our worthy orators come out to deliver their speeches? Because the barbarians will arrive today and they get bored with eloquence and orations”. The people spend an entire day waiting for the barbarians, but night falls and they have not arrived. Then news comes from the border that there are no barbarians. The poem ends (in the translation by Evangelos Sachperoglou) with the question “and now what will become of us, without barbarians? Those people were some sort of solution”.

Cavafy’s friend, the English novelist EM Forster, described him as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe”. He was certainly his own man. He made no attempt in his verse to conceal his homosexuality. And he also wrote Greek in his own unique way.

At the time that Cavafy was writing, there was no established or agreed-upon form of Modern Greek. When Greece achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire some five decades before Cavafy was born, attempts to replace Turkish as the official language led to a number of competing solutions to the problem of what form the standard written Greek language of the new nation should take. The two main variant solutions came eventually to be known as Dimotikí “demotic”, and Katharévousa “purifying”.

Katharévousa harked back to the glories of the Classical and Byzantine past, and attempted to purge Greek of foreign linguistic elements. Dimotikí resembled the dialects of the modern spoken language much more closely. The two varieties differed substantially in vocabulary and grammar, and during the 20th century there was considerable tension about which of the two varieties should be the language of government and education, with Katharévousa attracting more support from the political right, and Dimotikí from the left.

The brutal right-wing military junta which seized power in a coup in 1967 was particularly heavy-handed in imposing Katharévousa. Once democracy was restored in 1974, Katharévousa was totally discredited, by association, and it has now largely disappeared, though not without influencing contemporary Modern Standard Greek, as this developed out of Dimotikí, to some degree.

Cavafy stayed above this fray and went his own linguistic way, using a combination of forms from both variants, plus some from neither. With his eccentric spirit, he felt free to exploit all the resources of the Greek language, from Ancient to Modern, and from highly formal to very informal.

Remarkably for someone who has become so influential in the world of Greek letters, Cavafy never set foot in Greece until he was 38 years old.

Junta

Junta was at first simply a Spanish and Portuguese word referring to a council or committee. In earlier forms of English, it also appeared with the spelling junto. The word comes originally from Latin iuncta “joined”, from iungere “to join”. The corresponding French word is jointe, which has given us English joint.