As the classic cult film turns 40, Roger Domeneghetti considers the legacy of Flash Gordon and how the character has been a constant influence on sci fi, from Star Wars to Marvel.

Say the name “Flash Gordon” and most people will think of the camp, garish cult film with an iconic rock soundtrack by Queen, released 40 years ago this December. However, this belies the character’s true legacy, which laid the foundations for both the rise of superheroes in the 1930s and the boom of the cinematic science-fiction genre in the 1970s.

Flash Gordon was the child of a depression-era circulation war between King Features, a syndication company that distributed cartoons to thousands of newspapers across America, and its rival, the John F. Dille Syndicate.

In 1929 the Dille Syndicate launched the Buck Rodgers comic strip, based on Philip Nowlan’s novella published the previous year. The stories of the time-travelling astronaut were a huge success, prompting King Features to approach Edgar Rice Burroughs for the rights to his John Carter of Mars stories. When negotiations collapsed, the company turned to Alex Raymond, a 22-year-old artist on their staff, and tasked him with creating a suitable rival.

Flash was introduced to the public in January 1934 with the stark warning “WORLD COMING TO AN END: Strange New Planet Rushing Towards Earth – Only Miracle Can Save Us Says Science”.

In the next 12 breathless panels of that first strip our hero met Dale Arden, his long-term love interest; parachuted out of a crashing plane with Dale in his arms; was kidnapped at gun point by Dr. Hans Zarkov, a brilliant but unstable scientist; and blasted off into space in Zarkov’s homemade rocket. The words “To be continued” informed readers that Flash Gordon’s adventures had only just begun.

Soon Flash would land on the planet Mongo and do perpetual battle with its tyrannical ruler Emperor Ming ‘the Merciless’, the source of Earth’s existential threat. He would be variously helped or hindered by the inhabitants of the planet’s regions: Arboria, a forest kingdom; Frigia, an ice kingdom; Tropica, a jungle kingdom, plus the Hawk Men who lived in a flying city and the Shark Men who lived under the sea.

The comic strip was beautifully realised and its aesthetic vibrancy was a large part of its appeal. The original artwork for Flash Gordon #1 sold for $480,000 earlier this year and it’s hard not to think that Raymond and writer Don Moore were inspired to create this piece of colourful escapism as a reaction to the record low temperatures of the grim New York winter of 1933 and the dire economic situation engulfing the world at the time.

But Gordon’s attraction also came from the fact he was a figure that readers could identify with: a normal guy, albeit a professional polo player with a degree from Yale, battling evil in a foreign land.

The stories are replete with attitudes that are now at best outdated and at worst sexist and racist. The female characters had little to do but swoon over their male counterparts, be captured or rescued or, occasionally, at their most proactive, cast some sort of evil spell over the men.

The depiction of Ming, essentially Fu Manchu in space, conformed to offensive Asian stereotypes of the era and underpinned the demonisation of the Japanese in America, in particular following the attack on Pearl Harbour. Furthermore, in subsequent film adaptations, the despot was almost always played by white actors adopting ‘yellowskin’.

Despite this, Gordon was an instant success and by 1940 a daily strip had also been launched. At their peak, they were translated into eight languages and had a global readership of 50 million. They also had remarkable longevity only ceasing publication in 2003. Given this popularity, it was perhaps inevitable that Hollywood, then at the dawn of its Golden Era, would come calling.

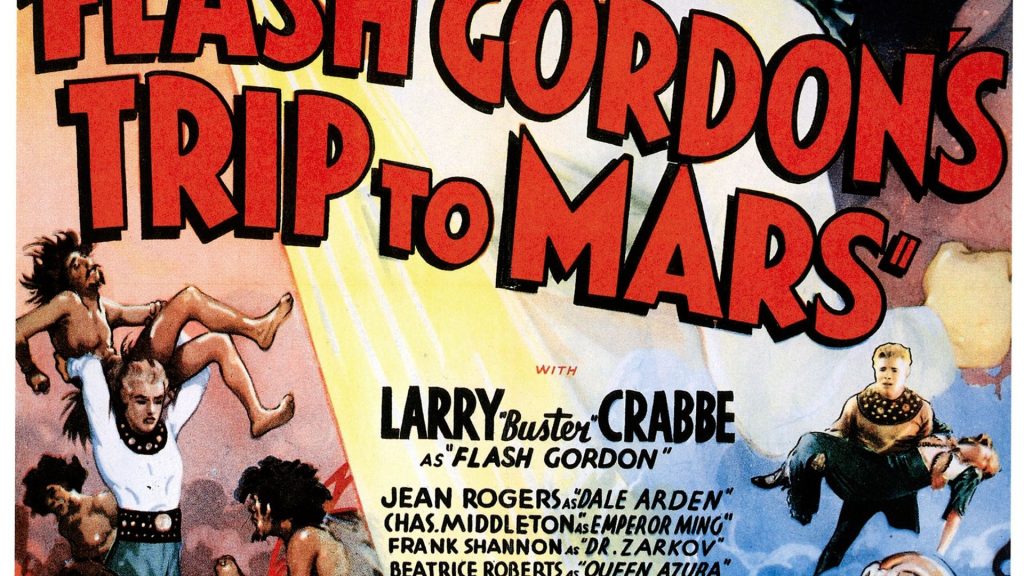

Universal studios bought the rights and released its first Flash Gordon serial in 1936. Starring Buster Crabbe, an Olympic gold-medal winning swimmer, they were, at the time, the most expensive ever produced and like the comic strips that inspired them, they were a huge hit. Crabbe appeared as Flash in two more serials released in 1938 and 1940.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Gordon’s popularity waned, his lack of complexity seeming anachronistic. He was soon usurped by superheroes whose stories more clearly reflected the post-war concerns of American life.

However, many of these comic book characters conformed to the template established by Flash Gordon. Superman’s creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster not only took inspiration from Flash’s clothes for the Caped Crusader’s vibrant costume but also essentially inverted Flash’s story.

While Flash travels from earth and becomes a hero on an alien world, Superman travels from an alien world and becomes a hero on earth. Similarly, Bob Kane’s first depiction of Batman, on the cover of Detective Comics No. 27, paid homage to Flash Gordon by mimicking the hero’s pose from an early Alex Raymond drawing.

The Buster Crabbe serials enjoyed a second life throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Re-edited into both series and films, they provided cheap content for the growing American TV networks and thus had repeat airings.

One of those watching was a young George Lucas. In the early 1970s, by then a filmmaker, Lucas approached King Features to secure the film rights to Flash Gordon, only to discover they were owned by Dino De Laurentiis who wanted Federico Fellini to direct.

Rebuffed, Lucas instead created Star Wars, drawing on his childhood obsession for inspiration. He later acknowledged the debt, writing: “Growing up in California, I was enchanted by two things … race cars and Flash Gordon. The first love I put to use in American Graffiti; the second eventually turned into Star Wars.” He also paid homage to his inspiration through a range of visual notes in Star Wars including among other things the text scroll at the start of the film and Princess Leia’s famous hair braids, which copied those of Flash Gordon’s Queen Fria. Even the fact that Star Wars was labelled “Chapter IV” was a nod to the 1930s serials.

The success of Star Wars kick-started the modern science-fiction films. With queues running round the block to see Luke Skywalker’s adventures, De Laurentiis decided to cash in his long-held film rights.

In a sense, Flash Gordon had come full circle. Just as the original cartoon was created in the 1930s to cash in on and compete with the success of a rival, so was this new iteration.

By now Fellini had departed the project as had replacement Nicolas Roeg. Sergio Leone passed and British director Mike Hodges got the job. Hodges, best known for the gritty British gangster flick Get Carter, seemed an odd choice for a sci-fi romp and would later reveal that De Laurentiis chose him simply because he “liked my face”.

For the role of Flash De Laurentiis approached Kurt Russell, who declined, and considered the then unknown Arnold Schwarzenegger, who was ultimately ruled out because of his strong Austrian accent.

In the end the role when to Sam Jones, another unknown, after De Laurentiis spotted him on an TV game show. Dale Arden was played by Melody Anderson, in her first staring role, while veterans Max von Sydow and Topol played Ming and Dr Zarkov respectively. Hodges supplemented the core cast with a roll call of British actors including Timothy Dalton and Brian Blessed as the king of the Hawkmen, a role he seemed born for and had coveted since childhood.

The vivid sets and ornate costumes which Hodges inherited make the film a visually accurate representation of the original comic strips. However, with a script by Lorenzo Semple Jr., who created the 1960s TV Batman, and a soundtrack by Queen, the tone was always likely to be high camp, despite De Laurentiis’ desire to produce a serious space epic.

It is perhaps this which explains why the film met with a lukewarm reception in America but was comparatively well received by British audiences more used to irony and the pantomime aesthetic.

In the the four decades since its release, Hodges’ film has acquired a cult status. Just as the Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s inspired a generation of directors in the 1970s, so the 1980 iteration inspired another generation of movie makers.

Seth MacFarlane’s comedy Ted has a central character whose love of Flash Gordon is a recurring theme. Sam Jones even has a cameo role as himself.

More recently, Taika Waititi acknowledged the influence on his Marvel film Thor: Ragnarok, saying “it had to be playful and over the top, this is unapologetically a space opera, and I’m going to pump this with colour and life and energy and humour, and cool music”. The Marvel Cinematic juggernaut, it seems, owes a debt to Flash Gordon, the original superhero.