CHARLIE CONNELLY on legendary literary character from France now enjoying some new exposure thanks to Netflix.

Paris, June 1929. A man calls at the Rue Saint Placide apartment of wealthy widow Madame Casanova, who is well-known in the city as a collector of gems and jewellery. He is handsome, about 30 years old and wearing an impeccably cut suit. Holding his hat to his chest he introduces himself as a Turkish military officer and connoisseur of precious stones who has come at the suggestion of a collector friend hoping he might be able to purchase some items from Madame’s collection.

Mme. Casanova is wary but invites the man in, asking polite but searching questions about possible mutual acquaintances and his background in gemstone collecting. He’s convincing and has impeccable manners so it’s not long before Mme. Casanova feels comfortable enough to bring out some items she might be prepared to part with for the right price.

The visitor pulls a jeweller’s eyepiece from an inside pocket and, holding it between two fingers, asks if he might possibly trouble her for a glass of water. The widow says she can do better than that, fetches a cut-glass decanter and pours out two glasses of red wine. They clink glasses. The visitor starts to examine the stones and pieces of jewellery laid out on a cloth in front of him and asks if she might turn on the lights to allow him to see them better. Mme. Casanova walks across the room to the light switch, returns and sips her wine.

The next thing she knows she’s waking up in her chair, several hours have passed, the room is dark, the fire has gone out and there’s no sign of either her charming visitor or the jewels he’d been examining. Placed against her wine glass is a handwritten note reading, “A thousand regrets at leaving you”. It’s signed Le Cambrioleur Gentilhomme, the Gentleman Burglar.

The Parisian newspapers went wild with this story. For one thing the sheer audacity of the theft was almost something to admire. For another, the inventiveness, chutzpah and élan of the thief, not to mention his note, begged immediate comparison from newspaper headlines to dinner table gossip with France’s greatest fictional gentleman thief – Arsène Lupin.

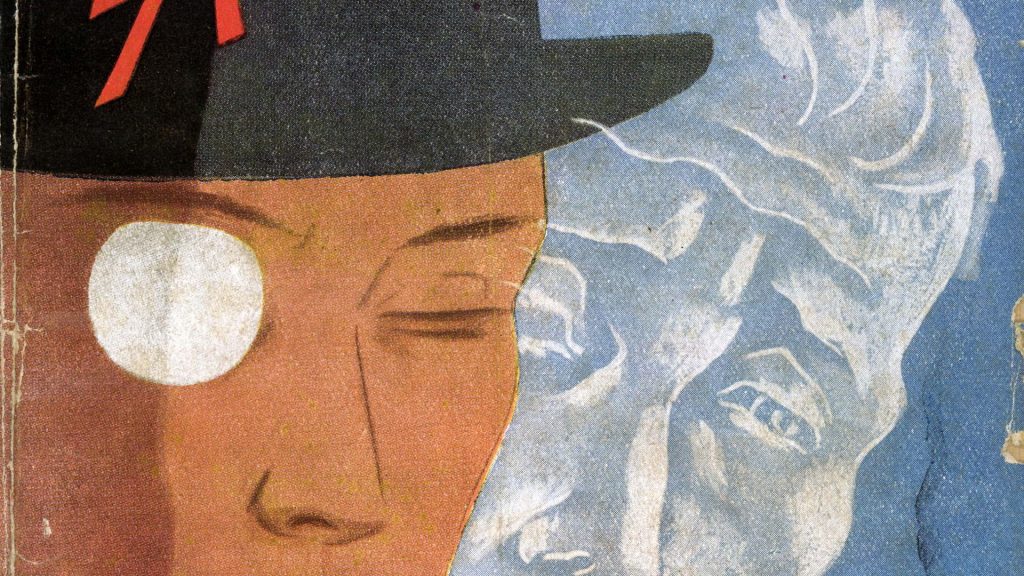

Usually portrayed in top hat, monocle, tailcoat and dress trousers, Lupin is one of the best-known characters of French fiction. Since he first appeared in a 1905 magazine story by his creator Maurice Leblanc generation after generation of new fans have devoured the short stories, novels and screen adaptations featuring the cultured thief with the heart of gold and inexhaustible ingenuity.

While his fame only spread across the English Channel as far as connoisseurs of crime fiction Lupin is so firmly enmeshed in French culture that even today his name is cited in connection with artfully dexterous real-life criminals.

In 2017 an audacious burglar named Vjeran Tomic went to prison for eight years after stealing five paintings in one night from the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, including works by Matisse and Picasso. At his trial Tomic compared himself with some degree of pride to Arsène Lupin. In 2010 a senior member of Air France’s cabin crew was labelled “a latter-day Arsène Lupin” by French police after she was arrested on 142 counts of stealing jewellery, cash and credit cards from sleeping business class passengers on long haul flights.

Lupin’s relative obscurity in the UK meant that as the Air France case went to trial a young Latvian man was able to carry out with some panache a series of ‘runners’ from some of London’s most expensive restaurants, racking up four-figure bills while charming staff then making a swift exit with his girlfriend without the vulgar inconvenience of paying. It was only after he was finally caught that the significance of the name under which he made his reservations became clear: Arsène Lupin.

Leblanc’s creation is currently enjoying an unprecedented level of global fame thanks to the Netflix series Lupin released a few weeks ago. In its first month Lupin was watched by an estimated 70 million people, easily outstripping recent hits on the platform like Bridgerton and The Queen’s Gambit. It’s not a straight dramatisation. Lupin’s literary adventures inspire Assane Diop, played by Omar Sy, to embark on a string of outrageous homage capers as he attempts to avenge a terrible injustice inflicted upon his father, who had introduced him to Leblanc’s stories when Assane was a boy.

“If I were British I would have said James Bond, but since I’m French I said Lupin,” said Sy recently about his original vision for Assane’s character, the child of Senegalese immigrants enduring overt and subliminal everyday prejudice. He passes on his love of the books to his mixed race son, making the series, as Sy puts it, “about putting a new face on what it means to be French today”.

The series is clearly helping to introduce another generation to Lupin’s adventures: a children’s edition of Leblanc’s first story collection, Arsène Lupin: Gentleman Burglar, last week knocked J.K. Rowling’s Ickabog off the top of the French children’s book chart, with publisher Hachette urgently commissioning an extra 85,000 copies to meet demand.

Not bad for a character created in a rush in response to a specific commission from a magazine editor. Lupin wasn’t intended to last beyond a few monthly instalments, let alone establish a character so vivid and enduring in the national consciousness he would still be captivating readers more than a century later.

Maurice Leblanc always dreamed of being a serious novelist. Born in 1864 to a wealthy shipowner from Rouen he studied in Manchester and Berlin before going into the family business then making a cursory attempt to study law. Eventually the draw of the Left Bank became too strong and he left his conventional life behind, moving to Paris to become a writer.

He scraped by as a journalist and occasional short story author for the Echo de Paris newspaper and in 1893 produced his debut novel Une Femme, ‘A Woman’, which, while it was reviewed sympathetically and sold respectably, failed to set the world on fire as he’d hoped. More books followed, all of them enough to make him a well-known figure on the Parisian literary scene but not the household name of which he’d dreamed.

In 1905 Leblanc’s friend the publisher Pierre Lafitte announced the launch of a new monthly magazine, Je Sais Tout, ‘I Know Everything’, and asked Leblanc for a specific kind of story. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories had become hugely popular across France. Would Leblanc, wondered Lafitte, come up with something similar for a specifically French audience? Holmes had first appeared in the English magazine The Strand sending sales and subscriptions through the roof, and Lafitte hoped his friend might be able to replicate at least some of that success.

Leblanc wasn’t particularly well-versed in the newly fashionable crime genre but, keen not to miss out on a commission, came up with The Arrest of Arsène Lupin, published in the summer of 1905. In this first story Lupin was portrayed as an already famous character, a gentleman thief, a lovable rogue for whom the reader was soon rooting even though he was, strictly speaking, the bad guy.

He may have been created in the wake of Sherlock Holmes but there were easier parallels to be drawn with Raffles, the gentleman thief devised by E.W. Hornung (who happened to be Arthur Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law).

Topical inspiration for Lupin may have come from the spring 1905 trial in Amiens of Les Travailleurs du Nuit, the Night Workers, a 40-strong anarchist criminal gang led by Marius Jacob who cheerfully robbed the rich in the name of social justice. Jacob himself was charged with more than 100 burglaries but his articulate defence speeches exploring the philosophy of theft won him many admirers on top of his life sentence.

Whatever its inspiration the story was well-received and when another appeared the following month it prompted a spike in sales so dramatic Leblanc realised he was saddled with his creation whether he liked it or not. Over the next 36 years he would produce more than 60 stories and novels starring his charismatic gentleman thief.

“Since around January 1906 when the third story was published,” he sighed in 1933, “I have been the prisoner of Arsène Lupin.”

Whether by accident or design Leblanc had created a figure that would be taken to the hearts of readers in France and beyond. The New York Times said of an English-language serialisation as early as 1909 that, “Like Raffles [Lupin] reflects in fiction – never a more sensitive mirror to the moods of society – something of a difference in the social attitude towards the criminal. For society is now rather less stern toward moral and legal lapses than was its wont and indulges in considerable sympathy with the underdog”.

Leblanc himself called Lupin “brave and chivalrous”, while his victims were “people inferior to himself, not worthy of sympathy”. He was endlessly adaptable, “the man of a thousand disguises: in turn a chauffeur, detective, bookmaker, Russian physician, Spanish bull-fighter, commercial traveller, robust youth, or decrepit old man”. Readers could pass anyone in the street and imagine it was the great Lupin, master of disguise.

The writer also scored by creating stories that were always more about wild fantasy than plausibility. Sherlock Holmes, Father Brown, Hercules Poirot and the other great crime fiction protagonists of the period worked because for all their brilliance and appeal they generally kept one foot grounded in reality. They showed their workings. By contrast Lupin’s adventures were always riproaringly outrageous, flourishing in the impossible rather than withering beneath it.

In truth the plots of the Lupin stories are not exactly nuanced and his characters are never particularly deep thinkers, but the genius of the stories lies in their thrilling suspense. How is Lupin going to get out of this situation, the reader wonders, in full knowledge that he always will and it will be unfailingly spectacular.

The nature and popularity of the two characters made it all but inevitable that Holmes and Lupin’s paths would cross. Seeking to piggyback on the English detective’s fame, Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late appeared in Je Sais Tout during the summer of 1906. Conan Doyle objected to the co-opting of his creation, meaning future Lupin stories would sometimes include an elderly, blundering English detective named, ahem, Herlock Sholmès, living at 219 Parker Street with his assistant, Wilson. Patriotism dictated that Lupin always came out on top.

“Arsène Lupin versus Herlock Sholmès!” the thief mused in The Blonde Woman. “France versus England… Revenge for Trafalgar at last!… Ah, the poor wretch!”

The Netflix adaptation drapes a new kind of patriotism over the venerable character. In Omar Sy’s hands Lupin celebrates a modern multicultural France that’s still coming to terms with its postcolonial present while anyone from any background rejoices in one of the great French fictional characters.

As for poor Mme. Casanova, a few weeks after the Paris robbery police in Brussels arrested a man claiming to be an Italian nobleman who had raised suspicions in the Belgian capital while paying suit to a wealthy widow. When apprehended he was wearing a ring that was later identified as being from the Casanova collection. Mme. Casanova recognised both the ring and the man’s mugshot when it was sent from Brussels. He turned out to be a Greek named Skurletti and went to prison for a long time.

That was the main difference between Arsène Lupin and those to whom his name and reputation are attached, especially at their own behest. Where the comparisons always fall down is that, unlike them, Lupin was never caught.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

FIVE GREAT LITERARY THIEVES

THE AMATEUR CRACKSMAN

E.W. Hornung (Penguin Classics, o/p)

Arthur J. Raffles was on the face of it the typical Victorian gentleman, immaculately turned out, living at a prestigious London address and playing cricket for the Gentlemen of England. He was also an ingenious thief whose stories are collected under the title The Amateur Cracksman, noting how his crimes are carried out for pleasure rather than the vulgarity of profession.

HENRY V

William Shakespeare (Oxford World Classics, £7.99)

Bardolph is the only character to appear in four of Shakespeare’s plays, an old friend of Prince Hal from his drinking days with a red nose that makes him the butt of many jokes in Henry IV parts 1 and 2. Light-fingered throughout, it’s when he’s caught looting a church after the Battle of Harfleur in Henry V that Bardolph’s life of crime catches up with him and seals Henry’s journey from wayward prince to warrior king.

THE ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

Arthur Conan Doyle (Collins Classics, £5.99)

Spectacular women thieves are few and far between in literature although they are better represented in television, film and computer games. Conan Doyle’s Irene Adler appears in A Scandal in Bohemia and it’s perhaps harsh to describe her as a thief as such: an opera singer with royal connections and a talent for disguise, Adler outwits Holmes over a potentially compromising photograph in her possession.

LES MISERABLES

Victor Hugo (Penguin Classics, £12.99)

The decision of a single moment can decide a fate of decades. That’s what Jean Valjean finds when in desperate poverty he steals a loaf of bread to feed his sister’s children. He goes to prison and spends decades after his release trying to live a normal, honest life beset by the constant attentions of police inspector Javert. Valjean is based on a real person, Eugene Vidocq, a convict turned successful businessman and philanthropist.

OLIVER TWIST

Charles Dickens (Wordsworth Classics, £2.50)

Jack Dawkins, known to all as the Artful Dodger, leads a gang of child pickpockets under the direction of Fagin, who has trained the Dodger well. Having grown old before his time, even wearing adult clothes despite being a boy, he grows to like but ultimately betrays Oliver. Eventually caught stealing a silver snuffbox, he ends up being transported to Australia.