Last week, for the first time in two decades, I dropped by my old ’hood in south-east London, harbouring notions of a cosy immersion in nostalgia. These were dispelled immediately when I found the house I grew up in derelict, fire-damaged, boarded up and the garden turned into a fly-tipper’s paradise.

So it was in fairly gloomy form that I set out along the route I once took to school.

Having walked past the house in which the medium Doris Stokes used to live – on summer mornings she’d be out pruning her rosebushes and we’d wish each other a good morning, me unsure if her greeting wasn’t actually some kind of prediction – I came around a bend convinced the next significant landmark would be in a similar condition to my old home. Or, more likely, not standing at all.

To my immense surprise the building was not only still there, it was apparently unchanged. A one-storey, flat-roofed, breezeblock construction with metal grilles over the windows that could never remotely be described as pretty, but to see it looking perkily whitewashed in the early autumn sunshine of a Sunday morning was a delightful surprise, not least after finding my childhood home to be a featured property on whatever the crack den equivalent of Rightmove might be.

On drawing closer to the building, my mood lifted even further when I realised that, not only was it still standing, it was still being used for the same purpose as when I was last inside it more than 30 years ago. A strange surge of pride went through me when I realised Grove Park public library is still going strong.

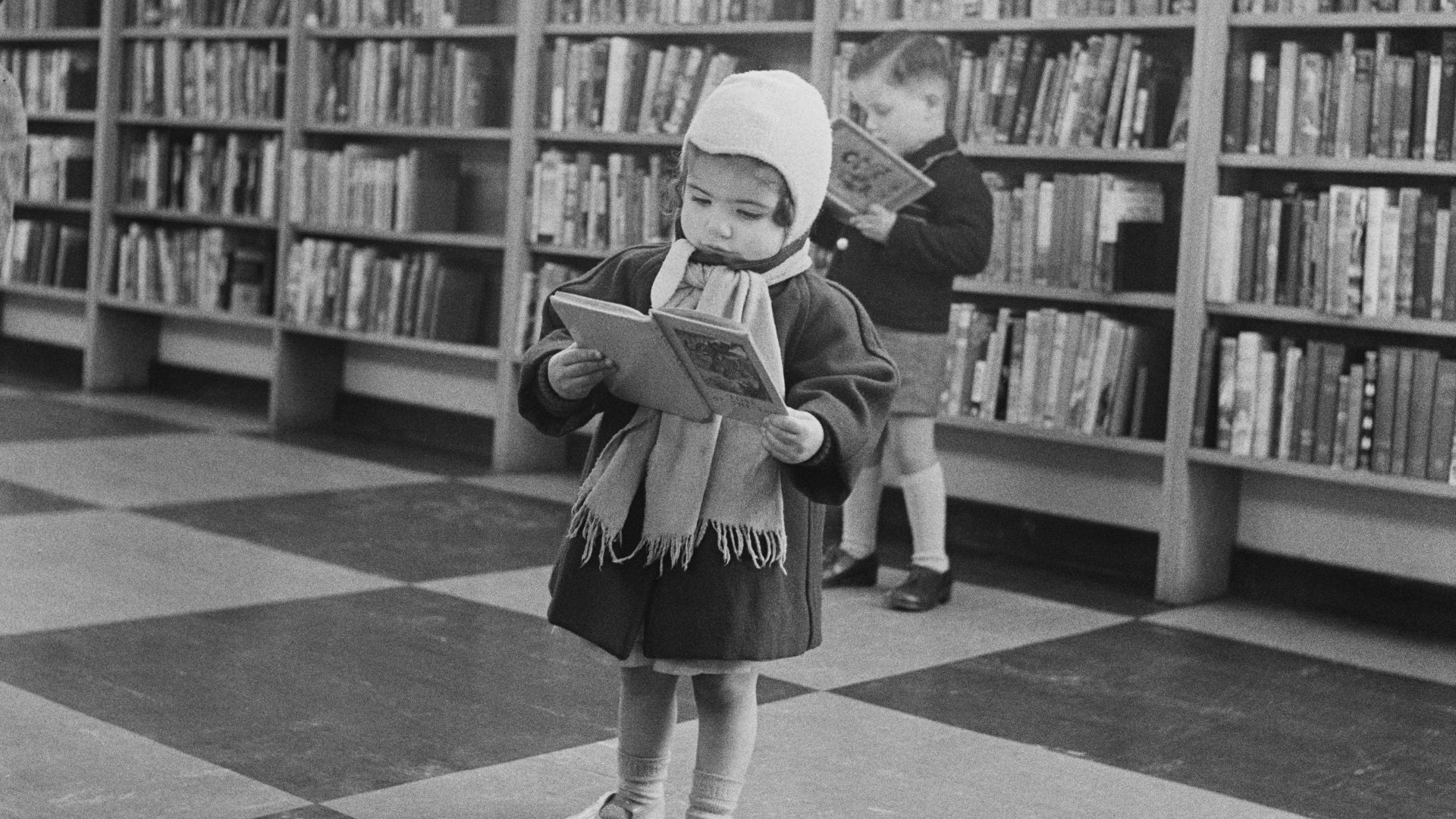

All thoughts of the sad demise of my old home dissipated as I stood before the library’s windowless blue doors, remembering how they were once the portal to a world of magic, adventure and escape. On most childhood Saturday mornings, my sister and I would be sent round to the library, little cardboard tickets with edges furred by regular use in our hands, to choose the three books that would see us through our spare time until the next visit.

There were occasions when life at home wasn’t the easiest, when the books we’d selected would become valuable refuges that opened up worlds in our imaginations to which we could escape thanks to the conjuring trick of extraordinary storytelling; the tiny Gaulish village of Asterix and Obelix, or the small-town junior teams of Michael Hardcastle’s football stories.

It would be an exaggeration to claim that Grove Park library saved my life, but it was certainly crucial in making it what it is today. The worlds contained on the shelves inside the graffiti-spattered walls of my little local library and their ranks of dog-eared, plastic-covered spines with the little stickers displaying their Dewey index numbers at the base helped convince me there was more out there than I might otherwise have believed. Not only that, I could take those worlds home with me. For free.

A couple of days after I’d stood before those library doors I learned of research announced by the National Literacy Trust revealing that more than half of Britain’s children do not enjoy reading in their free time. Fifty-six per cent of the 64,000 kids between eight and 18 surveyed expressed the opinion that reading outside school just wasn’t for them. This also means the percentage of young people who do enjoy reading has dropped to its lowest level since the NLT published its first survey all the way back in 2005.

The figures were even starker when applied to disadvantaged children: 60% of those who qualify for free school meals responded that they did not enjoy spending their free time reading. These kids were not just indifferent, or didn’t enjoy reading some of the time, they actively disliked the experience altogether.

While those statistics make grim reading, the news was not all cataclysmic. Many children expressed the opinion they would be more likely to read if they had access to a quiet space where they could do so, while a significant number of respondents who professed to not enjoy reading in their free time – mostly boys and children from disadvantaged backgrounds – said they enjoyed reading at school. If there is an issue here, it appears to be outside the school gates.

Which is where public libraries come in.

Having laboured for so long under the most culturally ignorant government in generations, it’s no surprise that our public libraries have been hit particularly hard by more than a decade of concerted austerity. Since the Conservative Party came to power in 2010, almost 800 public libraries have closed due to cumulative funding cuts estimated at around £250m, putting 10,000 staff out of work in the process. Despite more books being published than ever before, the level of book stock in British libraries dropped from 103 million books in 2005 to 75 million by 2019.

Yet for all they have been under concerted attack, libraries remain a British success story, beating the odds stacked heavily against them, cocking a snook at authority in the plucky manner of a 1950s Ealing comedy. For all the government’s apparent determination to target these civic outlets for personal development, in 2019-2020, the year leading up to the pandemic, we made 214 million library visits and borrowed 165 million books. In addition there were 130 million online library visits.

One in three adults visited a library that year and seven out of 10 people agree that libraries are an essential or very important community service.

Nearly all of us are convinced that public libraries are a very good thing. The trouble is, they are also the antithesis of everything this government stands for, a free resource that anyone can walk in off the street to make use of and stay for as long as they like, whether they’re browsing books to take home, using the free internet facilities or just killing a bit of time reading a newspaper.

Libraries represent a pure form of altruism, the ultimate in public service for the public good. They have no profit motive and encourage open-ended self-improvement among all strata of society without any specific economic aims. Indeed, the only way libraries could be more geared to upsetting Tories is if they started arriving from across the Channel in dinghies.

Yet libraries are the very cornerstone of levelling up. Not only do the individuals using them feel the benefit, so do the economy and the country. The knock-on effects are wide-ranging, with the Institute of Education finding recently that children who read for pleasure are better at maths and English than children who do not. The institute also estimates there are nearly 400,000 children in Britain who do not own a single book, making access to public libraries even more important.

The thought of so many kids out there not having the access to reading that I had, thanks in no small part to a little building in a south London backwater that opened up a range of plausible futures to me, is a deeply distressing one.

Grove Park library was an early victim of those funding cuts of the early 2010s and one of the first to close, but such was the strength of feeling among the local community the building was first renovated then reopened by volunteers in 2012. Issues with the lease threatened its future earlier this year but it seems those have been resolved and the library is safe, at least for now.

Most of the regular trips made by children are chores – the dentist, the doctor, elderly relatives, school – but to me the library was different, the library was exciting. The three little squares of cardboard were permission slips to indulge yourself in a way all but unmatched in childhood. You had a freedom to choose untainted by parental or adult influence.

At school you were handed books you were forced to read while whatever books you might have had at home had been selected for you by others. But here, the entire universe and all it contained could be yours.

It never occurred to me that this must have been the smallest library in the borough, let alone the city. Its stock must have been chronically limited, probably just the leftovers from the bigger branches. Yet it always felt as if the entire world of stories, knowledge and adventure was contained in a cheaply built shed with a leaky flat roof and all of it could be mine thanks to those three brown furry-edged tickets with my name on them.

I thought of all those Saturday mornings I’d spent making meticulous selections before taking my choices to the librarian, a glum-looking middle-aged man wearing thick glasses and a sports jacket with leather patches on the elbows, who would perform a dizzying sleight of hand to administer the return date thrice over with a thump-clack of his stamp that I can still hear today. It was the same for generations before and after me.

Grove Park Library opened in December 1953, meaning it will turn 70 years old this Christmas. I’m sure the building was never intended to last that long – it was falling apart when I was a kid, but thank goodness it’s still there. Perhaps it is held up by some of the magic its shelves have contained for seven decades now, the same magic that reassured the little boy I once was that there was far more joy and wonder in the world than life otherwise suggested.

If we can transfer some of that magic to even a few of those 56% of kids who feel they don’t like reading for pleasure then maybe this rain-lashed, wind-blasted rock on which we eke out our existence might have a brighter future than the grim, joyless grind our government seems determined to inflict on us might suggest.