Making a documentary on the extraordinary German film-maker Werner Herzog is almost as difficult and foolhardy as, let’s say, pulling a ship over a mountain.

But it’s worth it, according to Thomas von Steinaecker, whose film Radical Dreamer is being released into UK cinemas this week to accompany a retrospective season of Herzog’s films at London’s BFI Southbank. “I think I’m the first person to make a film about Werner who wasn’t Werner himself,” he observes drily. “He’s very protective – not of his image, but of his ideas and where they come from.”

Stars lining up in the film to contribute include Nicole Kidman and Robert Pattinson, Christian Bale and Patti Smith. More surprisingly, there are interviews with former Rocky star Carl Weathers – who appears alongside Herzog in Star Wars saga The Mandalorian and seems totally, charmingly perplexed by how the two of them ever got to be working together – as well as Oscar winner and Nomadland director Chloé Zhao and compatriot contemporaries Wim Wenders and Volker Schlöndorff.

“I’m an actress happy to go anywhere if it’s worth it,” says Kidman, who starred as explorer Gertrude Bell in Herzog’s 2015 film Queen of the Desert. “And Werner’s worth it, he’s really worth it.”

Smith calls him “an impossible dreamer” while Pattinson, who also featured in Queen of the Desert, very eloquently describes Herzog as elusive, saying: “It’s impossible to see the world as he does – you can try, but it’s impossible to get close to that vision.”

Christian Bale, meanwhile, recalls not being able to stand up for an hour after Herzog made him spin around without calling cut while filming Rescue Dawn.

All the old anecdotes of craziness are there. The new documentary nevertheless gets very close to Herzog, something few have managed over the years, even bringing the great director to tears. “I thought he’d be a scary, choleric artist,” admits von Steinaecker of his subject, “but I was surprised to find a very polite and friendly man, disarmingly tender.”

As a film-maker, actor, philosopher, icon, documentarian and personality, it’s fair to say Herzog is admired, revered, feared, mocked. He has voiced a character on The Simpsons and been the subject of several YouTube parodies mocking his habit of musing on the human condition, including one of him sharing his thoughts on Winnie The Pooh (“Why and how these animals exist in the wild is of no consequence”). A 2006 clip of him being shot with an air rifle by an unknown sniper while filming a BBC interview with Mark Kermode has gone viral several times (“It’s not significant,” he tells Kermode, showing his wound).

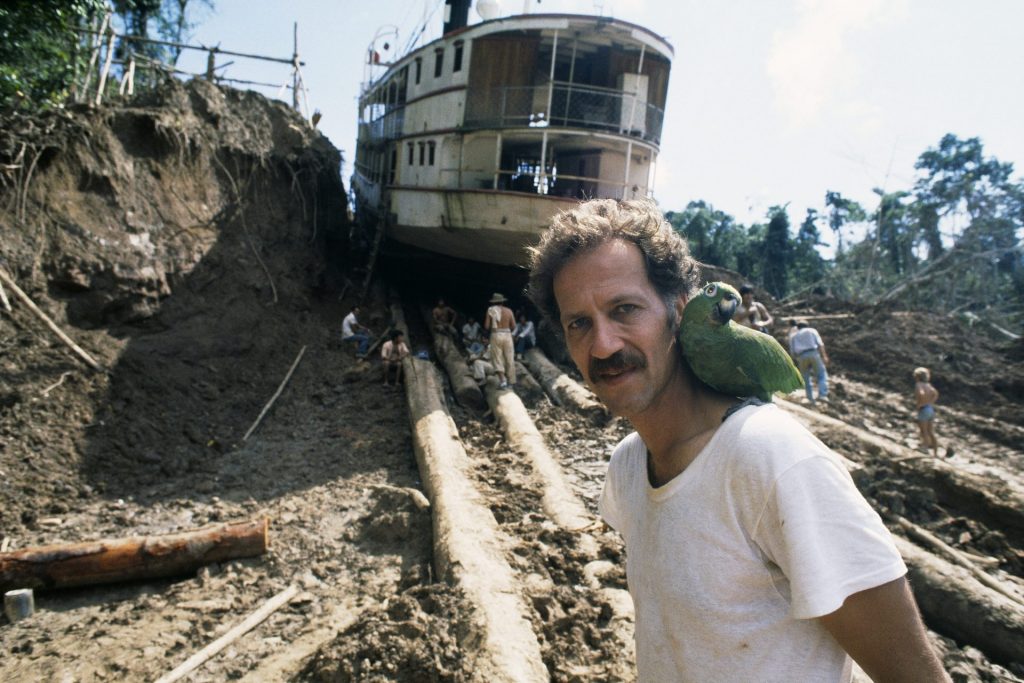

Herzog is also well known for pushing his actors and locations to breaking point, a reputation first forged during his astounding films with the actor Klaus Kinski including Fitzcarraldo (the one with the ship being pulled over a mountain) and Aguirre, the Wrath of God.

These films obviously crop up in the new documentary, which takes a chronological path through Herzog’s life and career. Herzog is now 81 but rarely shows any signs of flagging, physically or mentally. His 80th birthday party in Hollywood is considered one of the wildest nights there in recent memory.

The documentary pauses for comment from talking heads and interviews with Herzog himself. There is footage of Kinski raging on set in the Amazon jungle, but Herzog remains calm when reflecting on the relationship he himself chronicled in the 1999 documentary My Best Fiend. “Don’t ask me how difficult it was, please,” he entreats von Steinaecker of the actor he threatened to murder more than once.

“Werner was very guarded about going to certain places, emotionally and physically,” says von Steinaecker. “But I took him there nevertheless.”

They revisit the location, in Lanzarote, where Herzog made his remarkable absurdist film Even Dwarves Started Small in 1970. There’s a famous scene (among several) in which a car skids around in circles for quite some while and, amazingly, the tyre tracks where they shot are still clearly visible in the volcanic soil over 50 years later. It’s hard to say if Herzog remembers it fondly – vividly, yes, but fondly, who can tell? The doc maker asks him if they are good memories and Herzog simply says: “They are memories, neither good nor bad, and these marks on the ground simply say ‘I did good battle here’, and we move on.”

Battle seems the right word for a Herzog movie, particularly the impossible films of the Kinski era, from 1972-1987, films that now would surely never get insurance or clearance from health and safety. “They are documents, these films,” says von Steinaecker. “They say shooting them was like making a documentary in the 16th century, but they do remain evidence of another time, another world. You can’t make films like that even with the technology of digital cameras or even on your phone, but you can’t make them like that because we have no idea if people were harmed in the making of these films. It’s hard to believe nobody died.”

Herzog opens up about his mother and his impoverished childhood in a rural village called Sachrang, deep in the Bavarian Tyrol. He gets emotional talking about surviving on a loaf of bread, and refuses to enter the house where he lived. He is even more emotional when the film-maker suggests they visit a nearby waterfall in the woods. “That’s my place,” whispers Herzog. “The landscape of my soul.”

Sachrang has a reputation for ski jumping, and Herzog is filmed admiring youngsters in training, a jumping-off point for a clip of his 1974 documentary The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, about a world champion “ski flyer”.

In a revealing and quite moving passage in the new film, Herzog, himself a young jumper, reflects on the skills needed. “You lean into the abyss and, for a moment, transmute into a bird. I really wanted to fly. I find it a great injustice of nature that we do not have wings.”

“This is an amazing quote, isn’t it?” says von Steinaecker. “It says so much about him, about leaning into the abyss – he has never done anything else in his film career but lean into it, never shying away from it. I came to realise that this is a man who has often risked his life, and that of others, to realise his visions and dreams, so I think we can say making films gave Herzog his wings.”

For von Steinaecker, it was important to remain at one remove from his subject. “We are not friends now,” he tells me. “I don’t want to be friends with him and get caught up in the wildness of his world. I have seen how dangerous that can be and how all-consuming, but I am glad to know he liked my film.”

He says the two of them are from roughly the same area of Germany – “although Werner considers himself Bavarian, not German” – and that they initially bonded over Skype calls spent discussing the Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin, an outsider poet who struggled with mental health and schizophrenia and spent the final 36 years of his life in a tower overlooking the Neckar river until his death in 1843.

“I found Werner to be a true Romantic, prototypical of the German vision of the artist that was prevalent in the 18th and early 19th centuries,” he says. “Someone who would die for his art and put their visions first and foremost.

“It is a purity of vision that can be difficult to maintain, particularly in the modern world, but which I think he has always tried to protect, even when he went to Hollywood, which is the last place on earth you would think he could flourish. But somehow they got him there, and he certainly got America.”

Herzog now lives in LA and is very much a fixture, making documentaries and films from his base there but always travelling to extraordinary spaces for works such as Encounters At The End of the World – the one with the existential penguin tootling off to certain death in the Antarctic – or Rescue Dawn with Bale in Thailand in 2006, or the amazing Bad Lieutenant with Nicholas Cage in Louisiana and New Orleans in 2009.

“He’s altered America’s perception of Germans like nobody else,” says his friend Wim Wenders in the documentary. “Also, he has invented his own accent. That’s unique.”

Von Steinaecker tells me that the only way to get to Herzog is through his brother and producer Lucki Stipetić, a reclusive figure who is officially head of Werner Herzog Filmproduktion and who has spent a career in the background making his sibling’s visions come to fruition. He appears on camera in the documentary for the first time ever and took some convincing as to his own importance in telling the Herzog story. “He also told me this would be the first and last documentary on Werner’s work, so I had one shot at it.”

So von Steinaecker, better known as a novelist and historian than as a film-maker, deserves much credit for having got close to Herzog and brought him to tears, and got him to sit down for interviews in cars on the LA freeway, in the Canary Islands and in a snowbound mountain hut. “This was illegal,” confesses von Steinaecker. “And I think that’s why Werner liked it and trusted me – I found a place close to his heart, where he spent summer nights as a kid sleeping in a barn and I took him back to that spot and we shot an interview, completely under the radar and in defiance of the rules and the mountain rangers. That seemed to energise him, that at any moment we might get caught and fined or chased away.”

Radical Dreamer makes you want to rush out and watch as many Herzog films as possible; it reminds you of a time when extraordinary works of cinema such as this were hallowed events.

“He too was always on a search for new images, for something bigger, newer, bolder,” says von Steinaecker. “I don’t know if he ever found what he was looking for. But he seemed content at times and that was pleasing.

“I just don’t think there will be anyone like him again – cinema doesn’t have the scope to contain such large dreams, at least not in the way Werner made them happen. You can’t make Werner World again, so I am pleased I managed to capture what it’s like to be in it, and get out again.”

Radical Dreamer is in UK cinemas from January 19 and then on BFI Player and Blu Ray from February 19. The retrospective Journeys Into The Unknown – Films by Werner Herzog continues at BFI Southbank until January 31