Something has changed, and it’s not just the way the Conservatives have collapsed. The other half of the story could matter even more. It is the recovery of the Labour Party.

Until this autumn, the likeliest result of the next election was a hung parliament and a minority Labour government. To win outright, Labour needs to gain more than 120 seats. My Labour friends were often displeased when I pointed to the improbability of the party climbing that mountain in one go; but most of them grudgingly accepted my analysis.

Grudging time is over. For the first time in fifteen years, an outright Labour victory is now a real possibility. There is a reason for this that goes beyond the dramatic headlines of the past fortnight. It is not just the size of Labour’s current lead that has changed the prospects for the next election, but how it has come about. The slump in Conservative fortunes has been different in nature from anything before in the current Parliament.

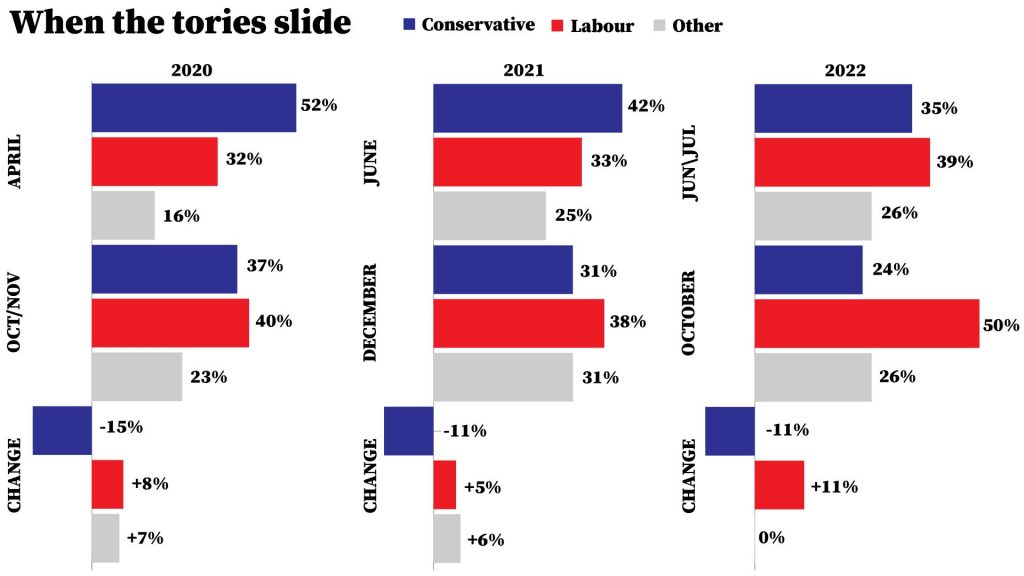

Recent weeks have seen the third wave of receding Tory fortunes since the last general election. The first was in 2020, during the early stages of the Covid pandemic. Between Boris Johnson’s time in hospital and the delayed second lockdown that autumn, Conservative support fell fifteen points, from 52 to 37%. The second time was last year, between the lifting of Covid restrictions in the summer, to the eruption of the Partygate scandal in December. This time Tory support fell eleven points, from 42 to 31%. Both last year and the year before, the outcome was a modest Labour lead.

However as the table/chart shows, on both occasions, Labour support rose by only half the amount that Conservative support fell. Essentially, every non-Tory party gained a bit from the Government’s unpopularity. What we saw both times was a negative shift in public attitudes: a move away from the Conservatives, not a positive embrace of any other party. Voters remained wary of Labour.

This time has been different. Labour has been the sole beneficiary of the latest Tory slump since Johnson was forced to resign.

That is not all. People who voted Conservative at the last election now say they would switch directly to Labour in numbers not seen since the mid 1990s. Normally, few voters switch directly between the two main parties. When we are told there has been, say, a five per cent swing from Labour to Conservative, or vice versa, the impression is that one voter in twenty has moved from one to the other. In fact, the simple number for swing combines a wide range of movements – normally, mainly to and from smaller parties, and to and from not voting at all. The 1997 and 2019 elections, with their big wins for Labour and Conservative respectively, were unusual in that there was a substantial direct move from Tory to Labour (1997) and Labour to Tory (2019).

Let’s put some numbers to this. Two million previously Conservative voters backed Tony Blair’s Labour Party in 1997, while 1.5 million converted from Labour to Conservative in 2019.

The latest numbers put both of these in the shade. Averaging the results from YouGov, Opinion and Redfield & Wilton, and converting their percentages to numbers, we find that as many as 2.5 million people who voted Conservative in 2019 now say they would vote Labour. This is three times the number of direct switchers when Labour was ahead last year and the year before.

Why has Labour gained so much more this year than last year or the year before? The Government’s economic failures plainly play a part: energy bills, food prices, mortgage rates, tax changes: have all played their part. In political terms, the current crisis has echoes of the devaluation of the pound under Labour in 1967, Black Wednesday under the Tories in 1992, and the financial crash under Labour in 2008. Each of those governments was defeated at the following election, even though many economists would credit each administration for the way it steered the economy towards recovery following each crisis.

In as far as there are any golden rules in politics, it is that a governing party can lose its reputation for economic competence overnight – but needs new leadership and years in opposition to regain it. Last week, immediately following the Conservative Party conference, YouGov asked people which was more likely to achieve a number of things, a Conservative government led by Liz Truss or a Labour government led by Keir Starmer. It comes as no surprise that Labour led on “managing the NHS” by 44-11%. Labour is almost always well ahead on health. The striking thing is that the figures for “tackling the cost of living” are almost identical: 42-14%. The figures for “delivering economic growth” were not quite so one-sided; even so, Labour’s two-to-one advantage (32-17%) is still remarkable by historic standards.

It seems that the old reputational dichotomy – Tories mean but smart, Labour nice but dim – is over, at least for now. Today we could be moving into an era when Labour is widely seen as nice and smart, versus Tories as mean and dim. If these perceptions take root, rather than being a short-lived response to our current turmoil, then the Tories could take years to recover.

There are also signs that the current crisis is enhancing Keir Starmer’s ratings. In early August, just 30% agreed that Keir Starmer “looks like a Prime Minister in waiting”; 42% disagreed – a net rating of minus 12. Opinium’s latest poll, conducted last week, gives him a net rating of plus five: 38% agree, 33% disagree. He is also seen as principled (a net score of plus 21) and compassionate (plus 11). Opinium gives him an overall net approval rating of plus nine. He is still way behind Blair’s approval ratings in the mid-Nineties; these were routinely plus 40 or more. But Starmer’s figures are now moving strongly in the right direction.

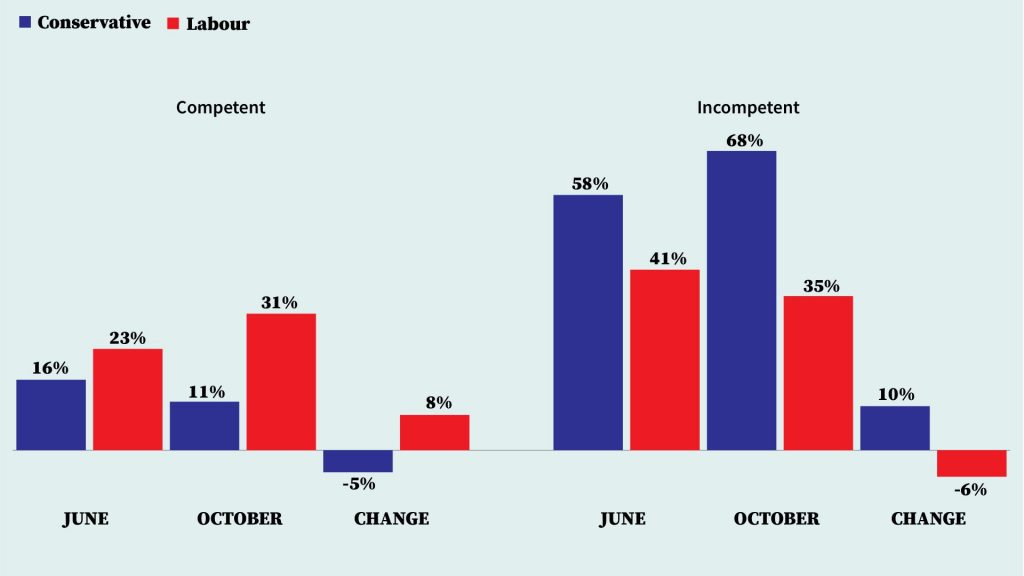

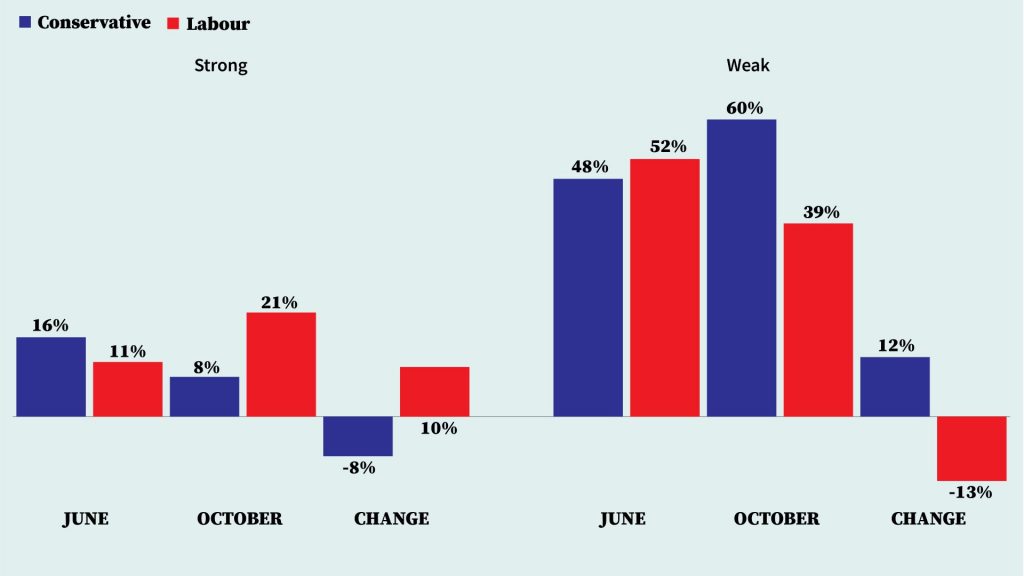

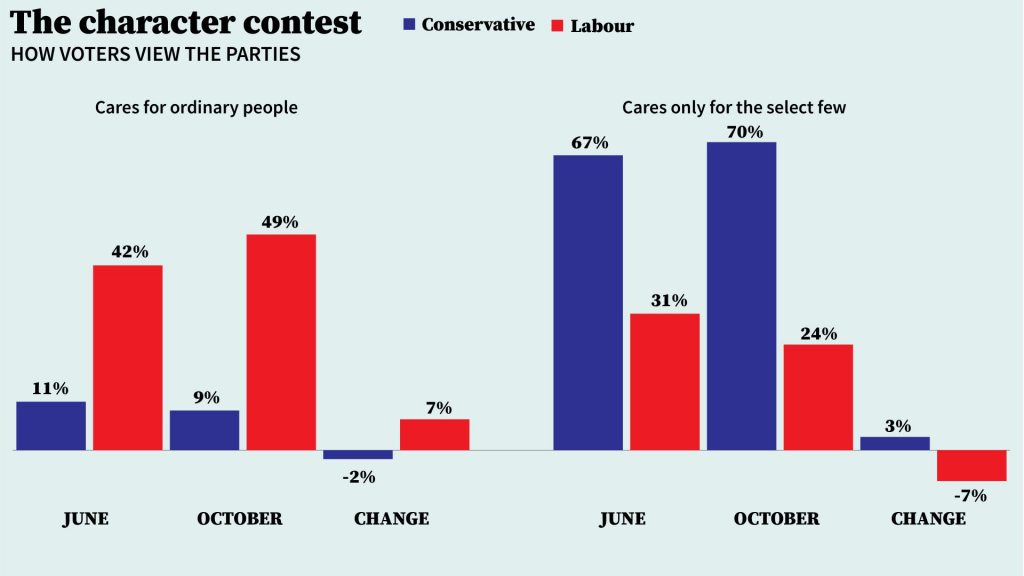

Overall, then, Labour has made real progress, albeit from a low base, on two of the key ingredients of a successful election campaign: good reputations for leadership and economic management. The third ingredient is a party’s overall character. Do voters regard it as competent? Do they feel it is on their side? Would it be strong in a crisis? Here is how the two main parties are viewed, and how the figures have changed since Johnson’s resignation.

The figures for the Tories during the run-up to Johnson’s resignation were terrible: surely they could get no worse? Oh yes, they could. They are now catastrophic. In contrast, Labour’s reputation has improved. It is now strongly positive on caring “for ordinary people” and has come close to wiping out a big deficit on competence. The party still has a problem on whether voters regard it as strong or weak. However, it has more than halved June’s huge deficit. Back then, the Labour had an even worse net rating than the Tories on this characteristic: minus 41 compared with minus 32. Today, at minus 18, Labour’s problems remain, but they are not nearly as bad as the Conservatives, on minus 52.

A word of caution: recent polling fluctuations indicate a volatile mood among millions of Britain’s voters. We cannot be sure that the Conservatives won’t climb out of the hole they are in. Let’s see if Labour can maintain 20-plus point leads until Christmas. In any event, one of the lessons from past parliaments is that even the most unpopular governments claw back some of their lost ground in the run-up to a general election. Two years before the 1997 election, Labour enjoyed a 30-point lead (Lab 55%, Con 25%). That had more than halved by the time of the 1997 election, which Labour won by 13 points (44-31%). In the summer of 2008, as the financial crisis took hold, the Tories were twenty points ahead of Labour (46-26%). The result of the 2010 election? The Conservatives won by seven points (37-30%).

If that pattern is repeated this time, the next election will be tighter than recent polls suggest. One further factor adds to the uncertainty. For various reasons, Britain’s electoral arithmetic is less kind to Labour than it used to be. The party now needs a 12-point lead in the popular vote to win outright. If Labour repeats its 1997 performance and defeats the Tories by 13 points, there would be no landslide, just a small overall majority.

Nevertheless, the party has taken a huge step towards electability. For the past decade, the single biggest factor holding Labour back has been a widespread terror among swing voters of what the party might do in power. Much of that terror has now been dispelled: it is no longer a barrier to victory. That is the most significant lesson from the latest polls. Labour can now give a cautiously hopeful response to Bing Crosby’s advice: eliminate the negative – largely done; accentuate the positive – underway but more to do.