To call Nick Timothy – once Theresa May’s right-hand man – a divisive figure is an almost lavish understatement, even within his own political party. To some, he is one of the Tories’ intellectual powerhouses and an essential figure in reshaping conservatism in the wake of a likely election defeat next year; a less combustible Dominic Cummings. To others, he’s an erratic liability who is almost single-handedly responsible for May’s calamitous loss of her majority in the 2017 snap election.

Whatever he may be in reality, he is overwhelmingly likely to play a bigger role in the Conservative Party after the next election – as he has been selected as the candidate for Matt Hancock’s old West Suffolk constituency seat. Its majority of more than 23,000 means the Tories are still expected to win it even on their current dire polling numbers.

One local association member, speaking about why they had chosen Timothy as their candidate, told the Press Association that they “did not want a career politician”. If that was the case, they have made a very strange choice indeed: Timothy started his career in the Conservative Research Department, before alternating between various public affairs jobs, think tanks, and working for Theresa May in three separate (and increasingly senior) roles. It is hard to imagine a CV that could better be described as that of a career politician than Timothy’s.

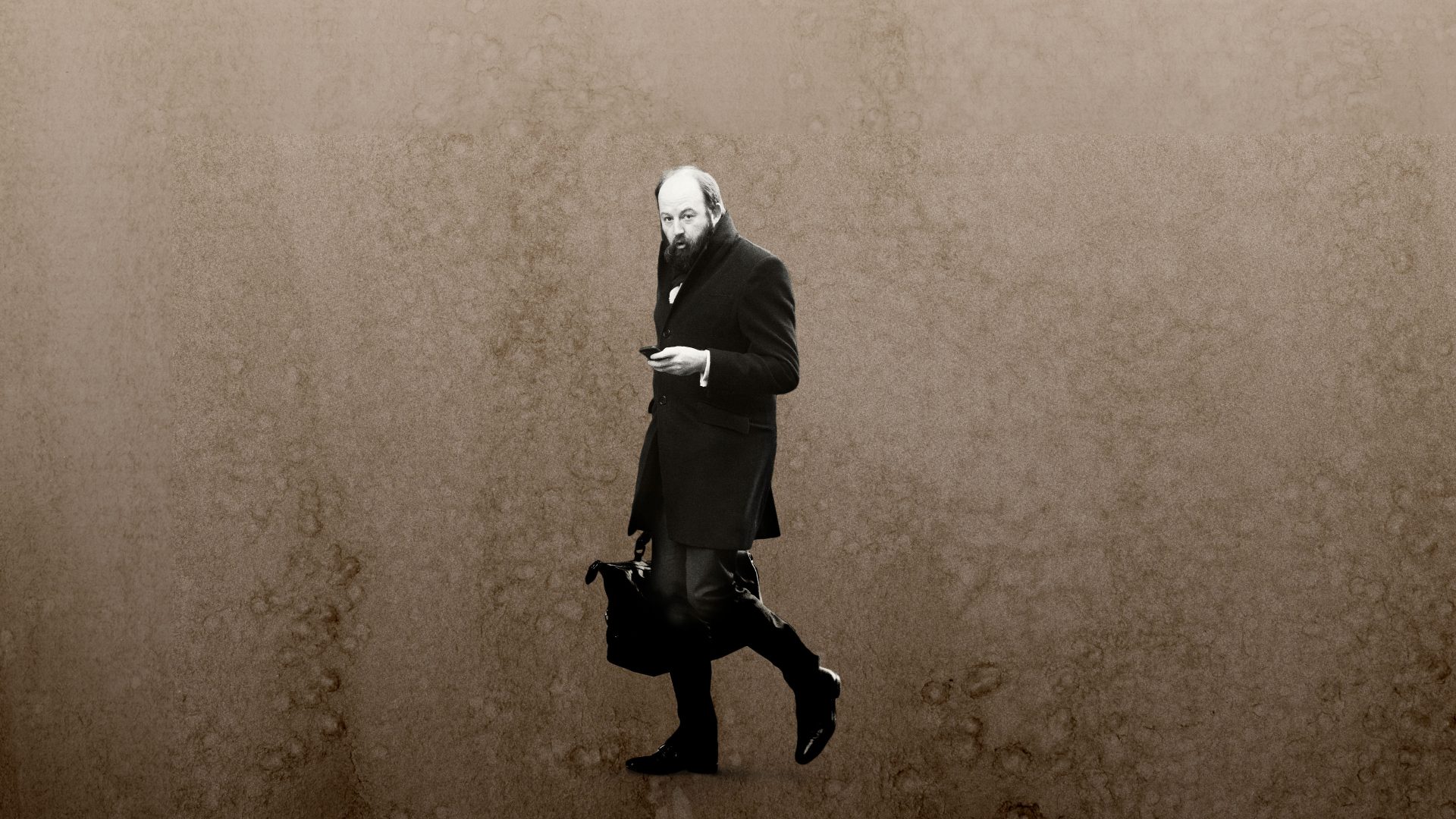

The man dubbed “Rasputin” for his unkempt beard (and presumably his mesmeric hold on May) has always cut a controversial figure, even before he had a public profile. During his time as May’s special adviser in the Home Office, he raised the hackles of civil servants around him who felt he was needlessly combative, did not consult (which meant he missed obvious flaws with policies), and could get May into trouble. In 2014, he was reportedly blocked by David Cameron from standing as an MP after being fingered as the source of a Spectator magazine story claiming May had “given up” on the “incompetent lightweight” then-PM.

On another occasion, an official recalled Timothy had repeatedly pressed May to interfere with the working of a body with statutory independence from the Home Office. The situation reached a point at which the official met with both May and Timothy in her office.

After Timothy had pressed once more for the independent body to do things his way, the official had to address May directly, and ask for clarification – if the official had understood Timothy’s request correctly, it would be unlawful, so surely he wasn’t asking for that? May very quickly backed down.

May was relatively popular among Home Office officials as effective, hard-working and competent – they were keen to note that she ended stop and search, and organised the Hillsborough Inquiry, though these rays of light were projected against the backdrop of the so-called hostile environment. Timothy, though, officials said was a liability – and so he proved to be, once May got into No 10.

Complaints started from the very earliest days of May’s reign, in which Timothy had been appointed joint chief of staff. Only the smallest inner circle of advisers had access to the PM, which meant civil service advice or countervailing views were shut out.

Even the No 10 spokesperson was not directly briefed by the PM, leading to a pattern of reversals from a poorly informed staffer doing their best to second guess what was happening in rooms they needed to be in, but to which they were denied access.

The error that still leaves Tories spitting with rage, though, is the so-called “granny tax”, a social care levy that was one of very few memorable policies from a complacent 2017 manifesto that seemed to take winning as a given, and so instead focused on minimising the potential for backbench rebellions once that win was made.

The policy was a levy on the homes of adults in social care, to be taken after their death to cover their care costs. It was rapidly dubbed the “granny tax” and led to days of horrendous front-page headlines – and an even worse response on the doorstep – for the Tories.

The torrid situation led to May having to perform a humiliating U-turn during an interview with Andrew Neil, all the while falsely and hopelessly pretending “nothing has changed”. Not only was the policy a disaster, but the handling of the fallout utterly undermined the “strong and stable” image upon which May’s whole campaign was built.

It is only because of just how much the British public did not buy into Corbynism that May survived as prime minister. Labour ran a campaign promising huge giveaways for everyone that would require almost no one to pay extra tax, and still lost to a campaign whose main promise was that they’d steal your granny’s house.

May survived, but did so only by jettisoning Timothy and his co-chief of staff, Fiona Hill. His exile, such as it was, did not take him far from Westminster – or from the CV of a career politician. He rapidly got a safe landing with a deal for a book on the future of Conservatism, and various roles authoring policy papers. He also got a Telegraph column, where Timothy lectures readers about the need to leave the European Convention on Human Rights, to remake the “woke” BBC, to halve the size of the civil service and to clamp down even further on migrants. He is prone to calls for complete overhauls of everything and has a penchant for melodrama (“The destruction of truth is at the heart of western cultural decline”; “Britain’s passive surrender to a woke minority risks everything we cherish”; “A crisis of masculinity imperils the foundations of the west”).

His status as a lightning rod continues. Timothy was accused of antisemitism after claiming George Soros was leading a movement to try to frustrate the public’s will on Brexit. Soros’s Open Society Foundations fund all sorts of NGOs across the world (disclosure: my former employer, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, receives OSF funding).

Given that Soros’s stated mission is internationalism, there should be little surprise that some of the groups OSF funded opposed Brexit, before and after the vote.

But to elide a real, grassroots movement as something orchestrated by a Jewish billionaire taps into problematic tropes of which Timothy should be all too aware. Timothy’s response to the allegations was startlingly similar to Jeremy Corbyn’s – he flagged his long-standing efforts campaigning against racism, including antisemitism.

Timothy’s mix of extremely high self-regard, inability to listen, and love of the spotlight means he will be one of the most noticeable of the next intake of Conservative MPs. The party will come to its own conclusions as to whether or not this is good news for them. The rest of us are left to wonder what it might mean for the country.