The moment was heavy with symbolism. As King Charles III stood in the throne room of Hillsborough Castle in County Down, the speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly and former IRA internee Alex Maskey expressed his condolences over the recent death of the king’s mother. As Gaeilge (in Irish).

“Ba mhaith liom comhbhrón a dhéanamh leat ag an am crua seo,” said Maskey, now a member of Sinn Féin, or We Ourselves, the dominant party in the region. Maskey’s words translate as: I would like to sympathise with you at this difficult time.

It was just one sentence – the rest of Maskey’s speech was in English – but for those of us old enough to remember The Troubles, those decades of bombs and bullets when more than 3.500 people, including the new king’s great-uncle, Lord Mountbatten, were killed, it was a solemn moment that felt significant. An audible nod to changing times nearly 25 years after the Good Friday Agreement that promised a break with the bitter past.

Young people with no personal memories of a time when the Irish language was championed as a form of resistance by republican IRA inmates on hunger strike in the Maze prison are the driving force behind a cultural revival that has breathed new life into a language long in decline.

“It isn’t, and I don’t mean this in a pejorative way, just wearing an Aran jumper, smoking a pipe and sitting around the fire telling stories,” said language advocate Ciarán Mac Giolla Bhéin, referring to the stereotypical image of Irish speakers that persisted when I was growing up in the Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking region) in the west of Ireland in the 1980s.

“It’s hip, it’s cool, it’s something you can do on TikTok or whatever social media you use. It’s something that has a place in the 21st century,” he said, noting that the rise of the language meant young people could have it all: they could take part in a sean-nós (traditional unaccompanied singing in Irish) but also go to an Irish-language punk concert.

Or they could go and see the provocatively named Belfast hip hop trio, Kneecap, who perform in Irish. Singing about drugs, parties but also working-class life in Belfast – their debut single was called C.E.A.R.T.A, or rights in Irish – their concerts draw thousands of fans, inside and outside the island of Ireland. Controversial they may be – in August, they hit the headlines after unveiling a mural showing a police Land Rover in flames near the traditionally nationalist Falls Road in Belfast – but their popularity also speaks to seismic changes in the fortunes of the Irish language, north and south of the border, in recent decades.

Although north of the border, the language is sometimes perceived as reaffirming sectarian divisions and traditionally associated with the nationalist or Catholic communities, its advocates say it can also be a unifier, drawing together Catholic and Protestant communities while also creating links with the Republic of Ireland and with minority language speakers across Europe.

In Northern Ireland, the revival has been spearheaded by Irish language schools, or Gaelscoileanna, which trace their history back to the late 1960s, when a group of families set up their own school in Shaw’s Road in Belfast, creating what became Ireland’s first urban Gaeltacht or Irish-speaking area.

Today there are around 30 Irish-medium schools in the region, another 10 Irish-medium units attached to English schools, and around 7,000 students studying in Irish. This means more communities are living their lives in Irish, with more adults learning the language outside the formal education system. And this has fuelled demands for a society that recognises Irish speakers’ desire to see their lives reflected in public institutions and services.

“In the last 10 years, we’ve had around 70% growth in (Irish language schooling), which is phenomenal, particularly considering overall enrolment was in decline,” said Mac Giolla Bhéin, who is chief spokesperson for the campaigning group, An Dream Dearg, which translates loosely as the Red Crowd, and comes from the Irish saying: dearg le fearg, or red with rage.

For years, the group has been pushing for more Irish-medium schools, more investment, and the swift ratification of the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Bill that would give Irish official status in Northern Ireland, as well as introduce measures to promote the little-used Ulster Scots language. The long-delayed bill passed its second reading in the House of Commons this month and will now proceed to the committee stage.

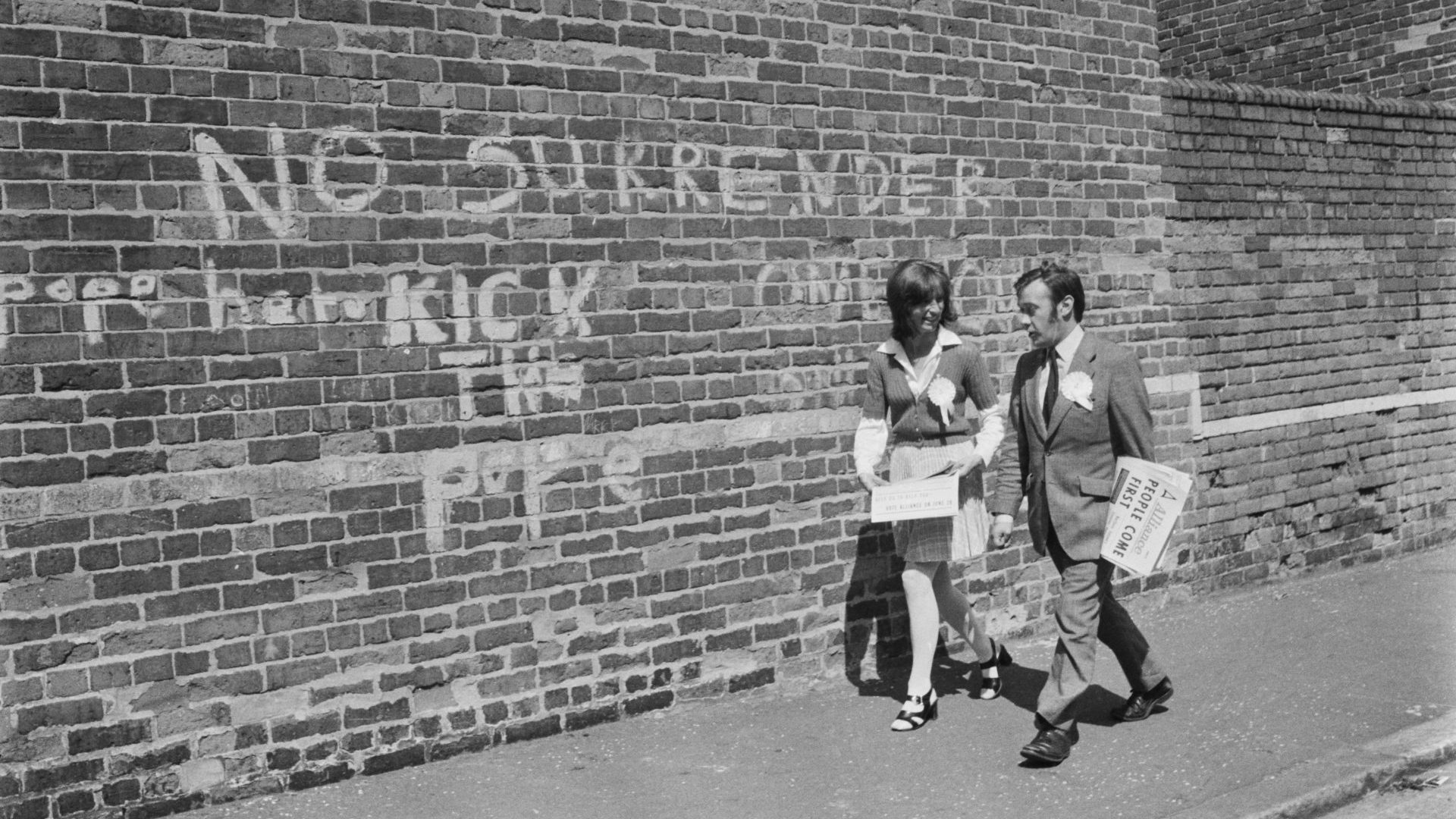

In May, thousands of people wearing red T-shirts took to the streets of Belfast to demand more recognition of the rights of Irish speakers – a key promise of the New Decade, New Approach agreement that restored power-sharing in 2020. They chanted: “Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam”, which translates as: a country without a language is a country without a soul. Many of the most vocal demonstrators were from the so-called “ceasefire generation”, young people born after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

The recent census showed that the number of people who said they had an ability in Irish rose from 10.65% in 2011 to 12.45%, while the number of people who said Irish was their main language rose from 4,164 in 2011 to 5,969, out of a total population of around 1.9m.

Alongside data that showed that people from a Catholic background now outnumber those from a Protestant background for the first time, the census cheered those who hope the six counties of Northern Ireland might one day be united with the Republic, where Irish is an official language and one of the core subjects in the school curriculum.

But Mac Giolla Bhéin says that while the language issue is indeed political, in the purest sense of the word, it’s less about that big political question of Irish unity and more about civil rights.

“The denial of rights to Irish people is political. That comes because of political choices people make,” he says, adding that the new generation of Irish speakers in Northern Ireland are no longer willing to accept this historical imbalance.

“You’ve these very confident Gaeilgeóirs, who’ve emerged through the education system, who’ve been involved in the community structures, and they’re becoming advocates themselves to speed up this revival project. Because that’s ultimately what it’s all about … the thread that unites us all is language revival. That’s what gets people out of bed every morning.”

The boom is not just confined either to those who identify as Irish – the language is also being learned by more and more unionists, who cherish their links to the British mainland.

People like Linda Ervine, whose husband Brian was briefly the leader of the Progressive Unionist Party. She helped set up the Turas (Journey) programme in traditionally loyalist east Belfast in 2012 to promote the Irish language and its history among members of her community.

She did so after she had an opportunity to learn some Irish herself in a taster course, and found herself on a “voyage of discovery” into the past. “As well as learning a few words and phrases, I was learning about the language and how we are surrounded by it … Coming from the Protestant community, I’d never had an opportunity to engage with the language and I wanted to share something that I had fallen in love with with other people and give them the same opportunity. I also wanted to say to the ones who were hostile, ‘Look, the perception you have about the language is incorrect’.”

After starting with around 40/50 students, Turas has so far this year seen 400 people enroll, mostly Protestants from East Belfast.

“When we first started, the majority (of learners) were very frightened,” Ervine tells The New European. “They didn’t want people to know that they were learning Irish, they’d come in wondering, ‘Do we know who’s here?’ Now that has changed. They love it, they’re telling their friends and neighbours and family, bringing other people along. There’s an absolute pride in it now.”

Niall Comer, a lecturer in Irish at Ulster University and former president of language advocacy group Conradh na Gaeilge, said the Irish language might have been considered divisive in the past but that is changing with many people recognising the educational benefits of bilingualism. He stressed that Irish language advocates never wanted to suggest that the language was the preserve of any one community or religious affiliation.

“Most people who consider the language to be a threat would consider a lot of other aspects of cultural diversity to be a threat as well,” he said. “A lot of (the opposition) is fear, and comes from a lack of education.”

That’s not to say the old sectarian tropes have died away completely or that the language is above the political fray. Some unionists accuse nationalists, especially Sinn Féin, of using the language revival to drive their push for a united Ireland but Conchúr Ó Muadaigh, advocacy manager for Conradh na Gaeilge, notes that Irish is just as historically relevant to the Protestant community, many of whom trace their ancestry back to the 17th century Plantation of Ulster – an organised colonisation by people from Great Britain.

“There are those who identify as British who are learning the language. They are on a journey, they realise it is one of the oldest languages in Europe … and that it predates any plantation or any of that,” Ó Muadaigh said. “Ninety-five percent of our place names derive from Irish. Many of our surnames derive from Irish so most people regardless of their background, ethnicity, religion will have a connection to the Irish language.”

As Douglas Hyde, then president of the Gaelic League and later Ireland’s first president, said during a speech in New York in 1905: “The Irish language, thank God, is neither Protestant nor Catholic, it is neither a Unionist nor a Separatist.”

*

The history of Irish in Northern Ireland is intimately bound up with history of the language south of the border, but also fashioned by the unique historical circumstances of the six counties that remained part of Britain after Irish partition in 1921.

The Plantation of Ulster led to a decline in Gaelic culture in the north but the language also fell into sharp decline across the British-ruled island of Ireland from the mid-1800s, particularly after a state system of primary education was introduced with a stated aim of teaching children English. The “tally stick”, or “bata scóir”, was introduced into classrooms and each time a pupil spoke Irish a notch was cut into the stick. A certain number of notches led to punishment.

The famine, or Great Hunger (An Gorta Mór) as it is known in Ireland, of 1845-1849 had a devastating effect on the numbers of people who used Irish as their first language. Many Irish speakers were among the one million people who died of hunger or famine-related diseases like cholera or typhoid, or the estimated 2 million who fled across the sea to the United States. An estimated 100,000 would die en route, succumbing to horrific conditions on the so-called coffin ships.

Efforts to revive and reclaim the language were at the heart of a wider cultural revival in the late 19th century with the creation of the Gaelic Athletics Association (GAA), which advocates for Irish sports such as Gaelic football and hurling, in 1884, and the Gaelic League in 1893.

Mac Giolla Bhéin said the cultural revival offered an alternative vision of society by challenging the idea that the Irish language and culture were somehow inferior to other European cultures. The language went from strength to strength across the island until partition in 1921, when it again fell into decline north of the newly drawn border.

“The language was completely wiped off the map (in Northern Ireland) in a calculated approach,” he said. “What you had then in every generation from the 20s onwards is Irish language activists, who were imprisoned for their activism … The language relocated itself underground because it was dealing with a very oppressive regime. The language was a target of that oppression.”

Brian Ó Conchubhair, associate professor of Irish language and literature at the University of Notre Dame, described the Irish language’s difficult position in Northern Ireland in a recent essay – Politics of Language in a (Dis)United Ireland – in the journal Irish Studies in International Affairs.

“After partition, reciprocal animosity grew. The Free State stressed Irish at every opportunity. In Northern Ireland, those in power viewed and used English as a ‘tool of cultural triumphalism’. As the Free State promoted and privileged Irish, Stormont penalised and punished it. Northern Ireland’s first education minister removed Irish from the curriculum, while unionist MP William Grant allegedly stated that the ‘only people interested in this language are the avowed enemies of Northern Ireland’,” he wrote.

During the Troubles, the Irish language was politicised with the leader of the Maze prison hunger strikers, Bobby Sands, calling on people to learn and speak the language as part of a Republican resistance to British rule. Many Republicans, including IRA leader Gerry Adams, first learnt Irish inside the prison system – the so-called Jailtacht, a play on Gaeltacht.

Language advocates hoped the Good Friday Agreement would usher in a new era of growth for Irish, not least because of the creation of Fóras na Gaeilge, which was charged with promoting the language across the whole island of Ireland. The Department of Education was also given a statutory duty to encourage and facilitate teaching in the Irish language. This unlocked strategic investment at a community-level in Irish-language infrastructure.

But despite a rise in the number of unionists learning Irish in some areas, activists still report hostility from some sectors of society, including political unionism.

In the past, the main unionist party, the DUP, has often been hostile to the resurgence of Irish, with some of its councillors openly mocking the language in Stormont. Famously, in 2014, DUP MP Gregory Campbell said: “Curry my yoghurt, can coca coalyer.” He was mocking the Irish phrase “go raibh maith agat, ceann comhairle”, which means “thank you, chairman”, a phrase used by nationalist politicians to begin their speeches.

More recently, language rights have been caught up in the wider political paralysis caused by the refusal of the DUP, which has held the education portfolio in Stormont for seven years, to return to the power-sharing executive until the Northern Ireland Protocol, which governs post-Brexit trade between the region, which is still in the EU’s single market, and Britain is scrapped.

Mac Giolla Bhéin says unionist hostility to the Irish language – as well as their intransigence on taking their seats in Stormont – is also alienating those who would like to see a more inclusive kind of society in Northern Ireland.

“One thing that is driving people more towards unity is the absolute opposition of the DUP to human rights across the board, not only language rights. This place is a backwater on human rights across many areas, from women to the LGBT+ community,” he said. “It’s this opposition that makes people say, ‘we can never build the kind of diverse pluralist society we all want to live in here’”

Conradh na Gaeilge sees the Identity and Language (Northern Ireland) Act as a critical part of their battle to combat hostile tendencies because it would introduce measures that would allow the use of Irish in the courts and ensure people could access public services through Irish.

Comer says legislation is important to enable a language to thrive, noting that it was the imposition of an English-language legal system in Ireland in the 1600s that made it easier to associate Irish with a lower class of society.

“There’s this common myth that the Irish language was not able to deal with legal terminology. That is nonsense,” he said. “It’s absolutely vital that people realise that they can engage with every aspect of life through Irish. It gives it a firm footing.”

For Mac Ghiolla Bhéin, the passage of the bill will not be an end in itself but rather will provide a starting point for further action.

“The idea is you get this, you implement it over a period of 10 years, you see what has happened, and then you reassess and you go again. Because there is no blueprint for language revival. It doesn’t work like that. A lot of it is trial and error.”

And he places the fight to cement the revival of the Irish language in a wider global context.

“People, especially young people, are looking for something bigger than themselves to be part of. We all speak the same, we all look the same, that only gets us so far … What we’re seeing in Ireland, and across the world – in Catalonia, in the Basque country and in Wales as well as other places – is that young people are looking around and saying there is something empty about this Anglo-American culture that is being pumped into us 24/7. There are alternatives and the best thing about it is that we can have both. It isn’t either or.”