Declaring Rwanda to be safe is one thing. It actually being safe is another.

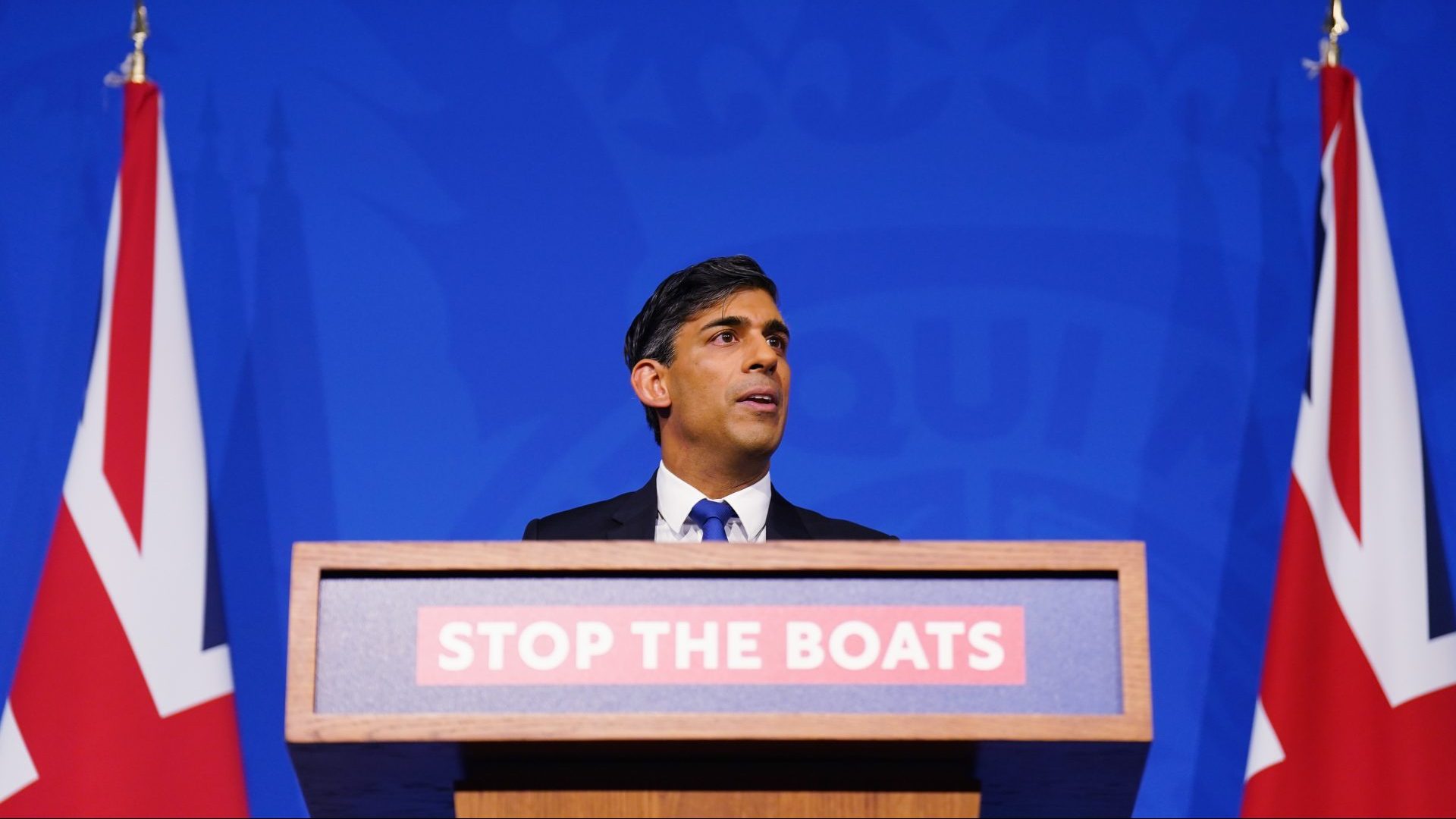

The government’s determination to send asylum seekers to the central African country is perhaps the most graphic illustration of its near-pathological disregard for other people and its fundamental lack of seriousness about governing.

Having loudly asserted that immigration is a problem, the government under multiple prime ministers has done little to manage it. Instead, they have devoted their attention, vast amounts of parliamentary time and over £500 million of public money on a proposal that has achieved precisely nothing other than advertise their cruelty, and complete moral collapse.

The unavoidable fact is that the UK government is planning to send refugees to a country that isn’t safe. And yet the legislation currently making its way through the Commons says otherwise. The Tory far right and its supporters in the press are cheering it on. But they are promoting a plan to send desperate, traumatised people to a country governed by a ruthlessly oppressive and authoritarian regime.

So far, the only people who have boarded flights to Kigali at huge cost to the taxpayer are a succession of Tory home secretaries seeking photo opportunities. Over £400,000 has been spent on ministerial visits to Rwanda so far, with current incumbent James Cleverly spending £165,651 of public funds alone on chartering a private jet to make a 24-hour trip last December.

In the unlikely event that the government manages to meet its initial target of sending even as many as 300 asylum seekers to Rwanda, the Guardian has calculated from National Audit Office figures that the scheme would cost £1.8 million per person, sent over its five-year duration. That is roughly five times what it would cost to send the refugees to stay at the luxury all-inclusive Palms Casino resort in Las Vegas for five years instead.

Unlike the government’s Rwanda plan, the Vegas alternative comes with free cancellation should it prove impossible for the guests to travel as planned. The government has already paid Rwanda £240m out of a minimum commitment of £370m of taxpayers’ money. None of this is refundable, even if it continues to be the case that no asylum seekers are ever actually sent to Rwanda.

A further indication of the Rwanda plan’s haphazard nature came in early April. It turned out that 70 per cent of the houses in Kigali that had been earmarked for deported UK refugees and beside which Suella Braverman had posed during a previous trip to Rwanda, had in fact been sold off.

As well as questions about whether the plan can work at all, there will also be a series of legal challenges to the premise of the legislation itself. This will set up a long-wished-for fight that Rishi Sunak hopes can be distilled into the culture war question: “Who rules Britain?” It’s one of his few remaining hopes for turning round those dismal opinion polls.

Since Boris Johnson officially announced the scheme to send a few hundred migrants to the country in April 2022, approximately 1.5 million people have immigrated to the UK, most for reasons such as marriage, work postings or to study. A fraction of these new arrivals – about 50,000 – came by irregular routes such as the much-discussed “small boats” across the Channel.

While it has created the desired political furore, the Rwanda scheme has been an abject failure from a practical perspective, as impartial legal, civil service and other expert advice made clear from the start that it would be.

A total of zero deportations remains the most likely outcome of this cruel, futile and absurdly expensive exercise in gesture politics, unless the government fulfils its threat to break its international legal obligations. No fair and independent legal body is likely to judge any time soon that Rwanda is a “safe country of asylum” in accordance with the requirements of the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention.

Rwanda is a dictatorship. Led by president Paul Kagame, the government is not only highly oppressive, but has also been stoking conflict for years across the border in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Kagame came to power in the aftermath of the horrific 1994 Rwandan genocide, at the head of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the rebel movement that overthrew the perpetrators of those atrocities. Over half a million people were murdered in the genocide, mostly from the Tutsi ethnic group to which Kagame belongs.

A reasonable case could be made that Rwanda in the immediate aftermath was in no shape for democracy and that some form of authoritarian rule was inevitable.

At first, Kagame and his colleagues made real progress in rebuilding Rwandan society. The country was stabilised and the government achieved a degree of justice and reconciliation through the use of traditional community “Gacaca” courts. With extensive western support, Rwanda began to rebuild itself.

Three decades later, Rwanda is not a stable, free and democratic nation. Instead, Kagame’s RPF has turned it into a police state. In his most recent “re-election” as president in 2017, he claimed to have won 98.8% of the vote.

Worse, independent international human rights organisations have documented the Kigali government’s abuses of any Rwandan who so much as hints at criticising it. According to a major report released by Human Rights Watch last October, “the RPF, since it came to power in 1994, has responded forcefully and often violently to criticism, deploying a range of measures to deal with real or suspected opponents.”

Those measures included “extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, political prosecutions, and unlawful detention, as well as threats, intimidation, harassment, and physical surveillance”.

The report also describes a campaign by the authorities to control and intimidate Rwandan communities overseas, including through arresting and threatening family members still living inside the country. In several cases, this programme of repression includes kidnapping or assassinating critics of the regime. In short, Rwanda is the sort of place people need protection from. It is not somewhere to which those seeking safety should be sent.

Rwanda’s obvious unsuitability for hosting vulnerable asylum seekers is compounded by its record of fomenting conflict and human rights abuses in its neighbour, the DRC, a vast and chaotically governed country. Its eastern regions, including the border with Rwanda, are 1,500 kms away from the Congolese government in Kinshasa.

In the initial aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, the surviving perpetrators of the slaughter had taken control of the huge camps in eastern Congo which housed hundreds of thousands of Hutus, who had fled the country, fearing revenge by the advancing Tutsi-dominated RPF.

This was the reason for Rwanda’s involvement in the DRC – but that justification has long since dissipated. The majority of these Hutu exiles – they numbered about 3.5 million in the late 1990s – have returned to Rwanda and, following stints in “re-education camps”, have been reintegrated into society. A smaller number of about 100,000 have settled permanently in the DRC. The militia that descends directly from the previous genocidal regime now consists of 500 to 1,000 fighters and presents little to no serious threat to Rwanda.

Nevertheless, Rwanda continues to interfere extensively in the DRC, through a proxy militia called M23. A December 2022 UN experts report confirmed that M23 is being supported, equipped and likely directed by Rwanda.

The DRC’s blessing and curse is that it contains vast quantities of valuable minerals to be mined, including gold, tin, cobalt and tungsten. During and after the Congo War of 1998 to 2003, this became a major motivation for Rwanda and other neighbouring countries, such as Uganda, to maintain an armed presence in the DRC.

Huge smuggling operations boosted Rwanda’s state coffers, as well as the personal finances of its elites. That illicit trade continues.

But the main reason for Kigali recently reactivating M23 to seize control of chunks of Eastern Congo, after a sustained spell of relative calm in the area, appears to be a desire for regional influence. A May 2021 infrastructure deal between president Félix Tshisekedi of the DRC and his Ugandan counterpart Yoweri Museveni seemed designed to sideline Rwanda strategically and economically. The deal also threatened to sharply reduce Kagame’s international political relevance.

From Kagame’s perspective, M23’s advances and seizures of territory have successfully preserved his power. But this has come at the cost of destabilising the DRC. Back in 2012, the UK government played a significant role in an international effort to compel Rwanda to reign in M23 and reduce the death and destruction it was causing in the DRC. Now that its ill-conceived refugee scheme has left it beholden to Kigali, it can no longer exert such influence.

Rwanda’s M23 proxy is notorious for its abuse of civilians, even by the grim standards of the region’s many guerilla forces. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) conducts extensive aid operations in the eastern DRC. It reports that up to a million people have been forced to flee their homes in the North Kivu region alone since M23 restarted the fighting there two years ago, and that it has treated at least 700 female victims of sexual violence at the hands of the guerillas. The area is now also facing a devastating outbreak of cholera and other deadly diseases.

Dr Denis Mukwege was awarded the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize for his monumental work in treating the victims of rape and sexual assault in Eastern Congo. He says, “Rwanda’s involvement in the destabilisation of the DRC, the plundering of its natural and mineral resources, and the commission of the most serious crimes, including the use of sexual violence as a method of warfare and as a strategy of terror, is widely documented”.

The government’s grim, politically-driven plan looks even worse when the reality of the Rwandan government is made clear. Its malign activities in the DRC are the clearest sign that it is no place to send vulnerable people fleeing persecution and human rights abuses. Britain could be putting them at risk of an even worse fate.

It is a horrifyingly clear expression of this government’s complete moral collapse.