The statue of Mother Russia dominates the skyline above the site of the battle of Stalingrad. You approach her colossal form up a long stone staircase that starts a short distance from the banks of the River Volga. Hidden as you climb, a shirtless soldier with a machine gun appears when you reach his level, symbolising the surprise that awaited the German army in the city. High overhead, Mother Russia holds aloft her sword as she urges the Red Army to advance. She looks over her shoulder at troops who were on the defensive, and now must advance to victory. Her forwards-pointing outstretched arm and backwards gaze are designed to capture the moment when the tide of the war turned.

Eighty years ago this month in January 1943, the battle of Stalingrad, which had begun the previous September, was in its final stages. Hitler’s forces, with their Italian and Romanian allies, had fought to capture the city, today called Volgograd. They wanted it for its strategic importance – crossing the Volga would open the way to the oilfields of the Caucasus and close the mighty river as a Soviet supply line. But Stalingrad also held enormous symbolic value. For what better humiliation could they visit on the Soviet leader than by capturing the city named after him?

Yet the Soviet resistance was stubborn and at times the Red Army’s soldiers defended their positions with the river just metres behind them. Their eventual victory changed not only the course of the war, but of world history. And yet contemporary Russia is a country where history is a tool to further its leader’s imperial ambitions. We have only to look at Vladimir Putin’s frequent references to “de-Nazification” when explaining his invasion of Ukraine to see the cynical use to which history is now being put.

In drawing on the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany to justify his own aggression, Putin has sought to present the Ukraine war as part of the same struggle against western invaders. But this is absurd. Reducing Ukrainian cities to rubble in a war of choice is not comparable with fighting an invader to secure your country’s survival.

To see the site of the battle of Stalingrad is to understand something of the way Russia has seen the West in wartime. Nothing stands out in Russian military history like the invasions of Napoleon, and Hitler – and to visit Volgograd is to understand how the latter was commemorated in Soviet-era sculpture, and how that memory has been adapted for the digital age of Putinism.

I first went to the Soviet Union as a language student in 1987, and my most recent visit to Russia was in March 2019. When I arrived, the harshest winter months were over – sometimes the frosts are strong enough to crack the paving stones. Workers were already repairing and renovating in preparation for the second world war victory celebrations on May 9, an annual event in Russia.

The Soviet-era museum commemorating the battle was nearby. Outside stood two tanks with slogans painted on their turrets: one said “For the Motherland”, the other simply “Fearless” – solid armour emblazoned with solid Soviet messages. The most interesting place to visit, though, was the basement of the city centre department store, which had been used as German headquarters in the final stages of the battle. With almost everything above ground destroyed in the fighting, the whole city centre in 2019 looked like what it was: the result of postwar reconstruction, with modifications added during the capitalist upsurge of the 1990s.

The basement is a small museum, containing some artefacts from the battle, as well as Soviet wartime propaganda material: leaflets and posters designed to sap the morale of the invader. One of these encouraged German soldiers to surrender, helpfully writing the Russian for “I surrender, comrade, don’t shoot!” in the Latin alphabet to help them out. Another showed a group of soldiers in the grip of a blizzard, and asked, in Italian, “Why have you come here? The Germans are conducting their criminal war with the sacrifice of your life.”

The German surrender at Stalingrad came on February 2 1943. “The moral and psychological significance of Stalingrad is colossal,” wrote the then Soviet ambassador to London – and prolific diarist – Ivan Maisky. “Never before in military history has a powerful army, itself besieging a city, itself become a besieged stronghold that was then annihilated.”

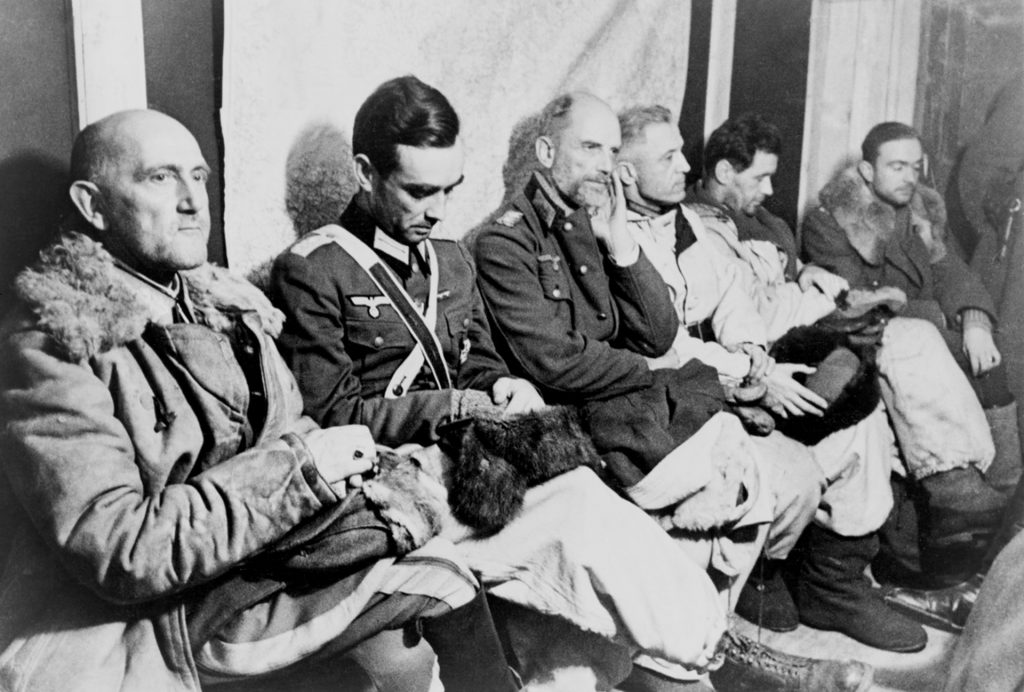

The propaganda value of the victory was enormous, and was exploited accordingly. Ninety-one thousand Germans were taken prisoner, including more than 20 generals, and the German commander, Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus. Those British and American correspondents who had been allowed to enter the Soviet Union once Stalin formed an alliance with the UK and the US had often been kept at arm’s length from the action. Now the Soviets gave them a front-row seat. Alexander Werth, correspondent for the Sunday Times who was also reporting for the BBC, was among them.

“There’s literally not a single house left standing,” Werth wrote, in a piece broadcast on the BBC on February 9 1943. Then he checked himself. “No, that’s not true,” he admitted, after his eye had been caught by “one little wooden house – and that’s all I could find of normal human habitation in a town the size of Manchester.” The same report described his encounter with the captured German generals. Werth, who had been born in Russia before his politically liberal family fled the rise of the Bolsheviks, felt very keenly the destruction of large parts of the land of his birth and he was keen to banish any lingering myths of Prussian military honour among Hitler’s forces. “There’s absolutely nothing to choose between the Nazis and the German generals who are supposed to be more gentlemanly,” he wrote. The sight of the captive commanders provided one of the most striking lines of his report. “Behind lock and key they radiated venom,” he said, “with their monocles and iron crosses and new Nazi decorations looking like mantelpiece ornaments.”

My most recent visit to Russia coincided with the fifth anniversary of the Russian annexation of Crimea. Earlier that week, I had watched the triumphant coverage on the main Russian TV evening news. It included shots of the then newly built Kerch Bridge linking Crimea and Russia, a section of which was destroyed last October.

Speaking at a concert to mark the anniversary, Putin made a direct link between Red Army heroism in the second world war (the “Great Patriotic war” in Russian) and the annexation – the Kremlin preferred “reunification” – of Crimea. “The actions of the people of Crimea and Sevastopol remind me of the actions of Red Army soldiers during the first tragic months after the breakout of the Great Patriotic war, when they tried to battle through to join their comrades and carried their field flags close to their hearts,” he told the crowd.

Along the banks of the Volga from the museum is another kind of memorial, entitled, “Russia: My History”. I was not tempted to visit. I had spent hours in the Moscow equivalent – they had recently sprung up in many of Russia’s big cities – just a few days before. To prepare the visitor’s expectations, the outside of “Russia: My History” in Moscow had a giant portrait of Tsar Alexander III with his famous words, “Russia has only two allies: her army and her fleet”. Inside, I was baffled by the size of the place, and when the person at the ticket desk asked me what part I wanted to visit, I chose the 20th century. The latest multimedia technology guided the visitor through wars and revolutions, the rise of Soviet power, and its demise. The message was clear: when Russia had stood alone, it had prospered. When it had foolishly opened up to western influence, it had paid the price. Ruin came from the West, whether in the shape of Napoleon, Hitler, or the 1990s experiment with democracy.

I thought of this when later that week I looked at the statue of Mother Russia. It stands on a hill that became the burial site of some of the 26 million Soviet soldiers and civilians killed during the war. “Don’t walk on the common grave! There are 34,505 people buried here!” says a sign. The translation is inadequate. The word for “common” in Russian has as its root the word “brother” so “brotherly grave”, with its evocation of brothers-in-arms, would be more accurate. I spent that afternoon in the company of a young tour guide who had agreed to take me round the sites on his day off, which was great for both my rusty Russian and my understanding of the city’s history. We were also able to see the changing of the goose-stepping guard in the “hall of military glory” that contains the eternal flame on the hill’s lower slopes. There was no digital technology here, but solid Soviet sculpture

My own reporting from Russia began as that era ended. Having grown up during the cold war, I was one of a generation that rejoiced as travel to Russia – a country that had always fascinated me – became easier. For journalists, it could also be much more dangerous, nowhere more so than in Chechnya, and especially during the first war in the winter of 1994-95. Already humiliated and embittered by the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow sent a massive military force to crush rebellious Chechen separatists.

Many years later, when I was carrying out research in the BBC archives, I came across Werth’s description of Stalingrad at the end of the battle and saw in my mind the Chechen capital, Grozny, in March. It was the month that Putin was first elected president. Then, as the second Chechen war came to an end, the city centre was rubble. Few buildings still stood; none was undamaged. Burnt-out windows stared back at the onlooker like the sightless eyes of the dead.

There is a historical line that runs from the second world war to Ukraine, but it is not a successive story of military glory. What Stalingrad shares with Grozny – and now Mariupol and other Ukrainian cities – is ruthless killing.

The glory and sacrifice of Stalingrad will endure, although from now on Russia’s neighbours, and the rest of Europe, are unlikely to celebrate anything related to the Russian army. The monuments and museums built in the last century have an air of permanence about them, but “Russia: My History” does not. I came away from my visit realising that there was not one single physical object in the entire exhibition: it consisted entirely of videos and virtual images, all liable to easy editing or manipulation.

Putin’s own wars are unlikely to be revered in the way the statue of Mother Russia remembers Stalingrad. He has been doing his best to put out the lamps in Ukraine this winter, but once Putin loses power, however that happens, the projections in “Russia: My History” may also be stopped – and his version of history will disappear with the simple flick of a switch.

James Rodgers is the author of Assignment Moscow: Reporting on Russia from Lenin to Putin (2023, new edition May 2023) and a former BBC Moscow correspondent. He now teaches Journalism at City, University of London