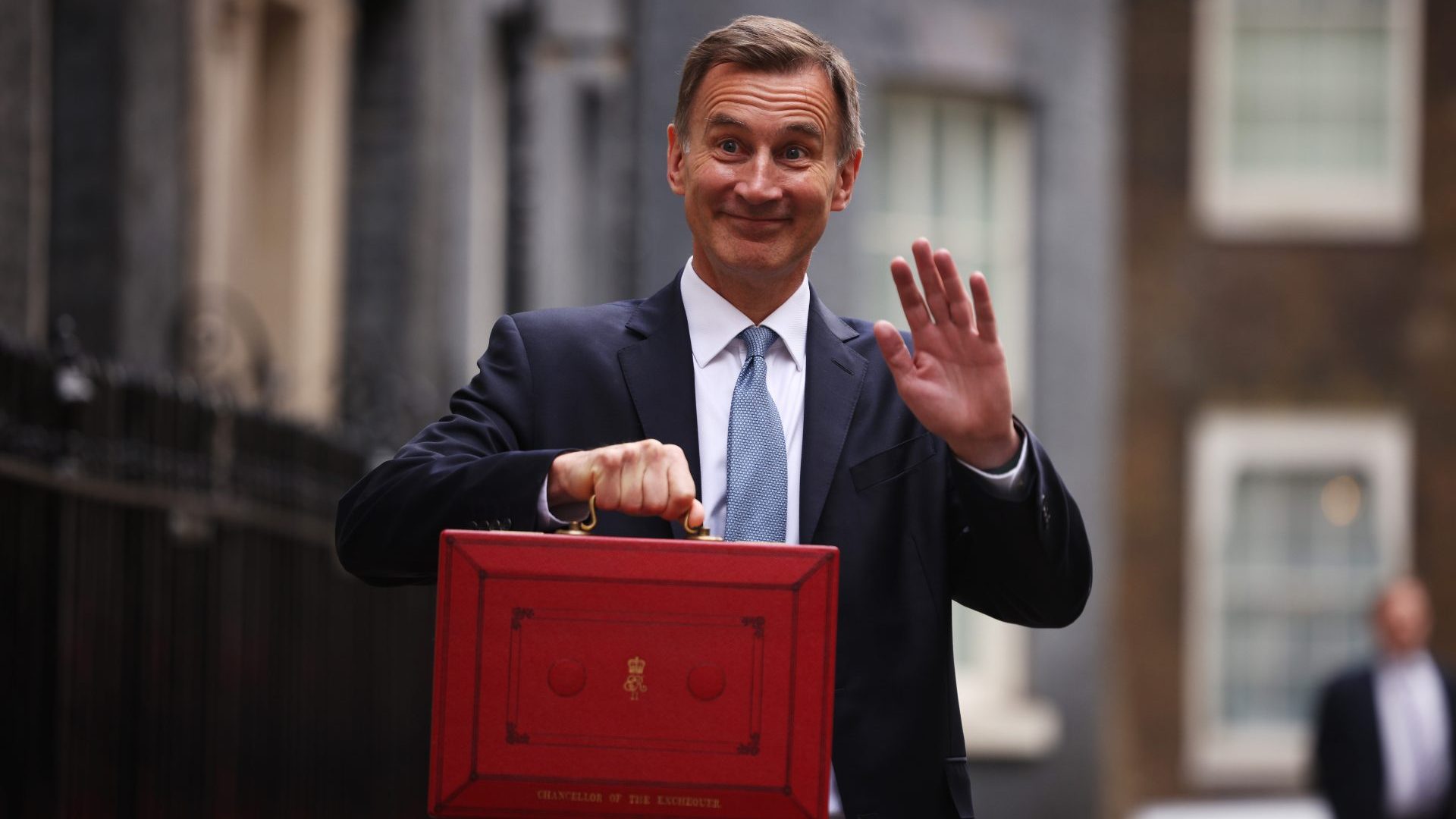

Jeremy Hunt wore a self-satisfied smirk as he delivered his budget speech last week. Unfortunately for the chancellor, this is his default look in most circumstances, but it is rarely appropriate and it certainly grated as he reeled off a series of statistics that, however upbeat the presentation, pointed to a continuing fall in the national standard of living.

The big reveal of the budget, a 2% cut in National Insurance, was as well kept a secret as Nigel Farage’s enthusiasm for the occasional pint. What was not revealed in Hunt’s speech, though, was quite what would be left of our over-stretched public services after the changes had been implemented.

No matter what agonising the budget may cause its authors, it is always an absolute nightmare for those trying to make sense of it. The speech itself is, inevitably, light on details, sometimes omitting quite important changes.

It is the accompanying Treasury documentation, the Red Book of numbers and the departmental explanatory statements, that can throw light on what is actually being proposed for the economy. The challenge for journalists and other pundits faced with reams of information is to try to find the truth of what is being planned, and it can take days for the full story to emerge. The impact of Hunt’s budget on defence and on local councils was only really beginning to be measured days, rather than minutes, after he sat down.

Some proposals have been given such cursory thought that they very quickly unravel under scrutiny. That was the case with George Osborne’s efforts to change the VAT regime for fast food back in 2012. What became known as the pasty tax rapidly evolved into a campaign to protect Cornish Pasties from what was portrayed as a vicious tax grab by a metropolitan elitist who had never even sampled the delicacy.

When the then prime minister, David Cameron, tried to support his chancellor by claiming to have enjoyed a pasty very recently from an outlet that had, in fact, closed more than two years previously, the government had to admit defeat and the idea was shelved.

But Osborne only got into the mess because the budget has been allowed to degenerate into such a nonsensical exercise in headline-grabbing and, all too often, a cynical effort to dupe the public, particularly in advance of an election.

This financial year, the government will spend around £1,200bn. Yet the first item Hunt mentioned was his decision to spend £1m on a memorial commemorating the contribution Muslims had made to the UK’s war efforts. If he had to itemise where every £1m was going, the chancellor’s stint at the dispatch box would be interminable.

So isn’t it time to rethink the shape and purpose of the entire exercise? In the corporate world, it is important to draw a line at the end of the financial year and examine the state of the balance sheet. The same is true for the country.

It is equally important to have forecasts that endeavour to show what basic income and expenditure might look like over the next couple of years, bearing in mind that forecasts can always be blown off course by events. That is why sensible governments like to have a cushion against potential difficulties. Every household needs its “rainy day” fund, just as every company should have reserves to cover its running costs for a period if trading becomes difficult.

What a national budget should surely be about is deciding what the country wants the state to be responsible for and then how that spending should be funded. These are broad-brush decisions within which the scope for disagreement and debate is endless. But a degree of long-term certainty over intended levels of tax raising and government spending would be hugely beneficial to all.

At the moment, the UK has a tax code that gets fatter every year. The existence of an Office of Tax Simplification had been a long-running joke since it was established in 2010. Last year the government acknowledged that it was no longer funny and shut it down, but the tax system continues to become ever more complicated.

The annual budget and autumn statement currently give the government two opportunities each year to add further complications. And yet, ideally, a grown-up administration should be able to set the overall picture of what it wishes to fund, determine the split between direct and indirect taxes with which it aims to achieve this, and then keep changes to a minimum while ministers and their managers try to do the best with the resources they have been given.

The Swiss have a budgetary system that goes some way towards this ideal. The central government is held to a relatively narrow remit, while many spending decisions are pushed out to the regions and, often, decided by referendum.

A greater level of devolution in the UK could curtail central government’s capacity for meddling. But there also needs to be an acknowledgement that managing an economy is an ongoing process in which key decisions cannot be restricted to one or two days a year.

For many local authorities now hovering on the verge of bankruptcy or already over the edge, the prospect of an imminent end to the Household Support Fund was terrifying. The budget brought the welcome news that the fund will be extended for six months.

But the local authorities needed that knowledge months ago. The fact that they had to wait for it to be packaged up as part of Hunt’s grandstanding demonstrates the craziness of the current system.

Liz Truss would never admit it, but “fiscal events” don’t make for sound finances.