A few weeks ago, writing cheerfully in these pages about the return of live literary events after the pandemic, I described the buzz of anticipation when arriving at a venue to see “the two chairs on the stage separated by a small table with a jug of water and two glasses on it, the ultimate literary still-life”.

There’s a reassuring symmetry about that scene: the low table in the centre flanked by armchairs angled towards each other in such a way that moderator and author can chat naturally while also taking the audience into their confidence. It’s a view pregnant with imminent discussion and egalitarianism, the opportunity to hear and interact with a favourite author in a setting designed to enhance intimacy. As set-ups go it’s about as non-confrontational as it gets.

On August 12, images of just such a cosy tableau – the table, the armchairs, there was even a rug – were beamed from New York state all around the world, but something was horribly wrong. The empty chairs in the photographs prompted not tingling anticipation but dreadful poignancy as a short distance beyond them a group of Chautauqua Institution staff and audience members fought to save the life of Salman Rushdie and restrain the

man who had just attacked him.

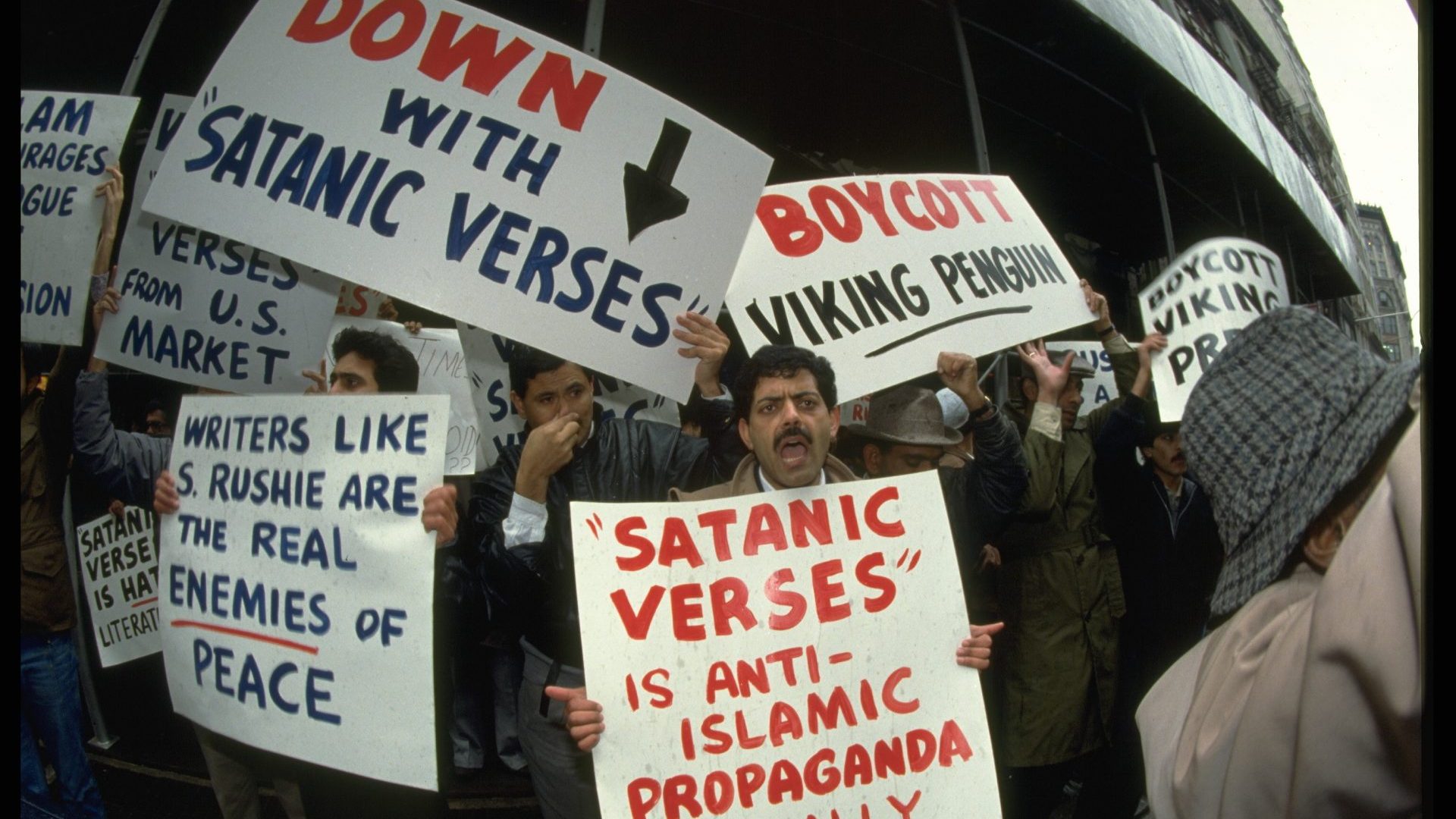

At the time of writing, the motive of Hadi Matar for what appeared to be an attempt to murder the 75-year-old author is unconfirmed, but it seems likely he was attempting to carry out the fatwa declared in 1989 by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini in response to perceived blasphemy against Islam in Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses, published the previous year.

It’s more than three decades since Rushdie was forced into hiding but he had gradually come to live a relatively normal life in extraordinary circumstances. It’s often forgotten these days that many people have already died as a result of the fatwa, from the 18 killed in 1989 during demonstrations in Islamabad and Mumbai to Hitoshi Igarashi, translator

of the Japanese edition of The Satanic Verses, murdered outside his office at

the University of Tsukuba in 1991. It took considerable bravery on Rushdie’s

part to emerge back into everyday society and make semi-regular appearances at events, especially as the bounty on his head was increased to

more than $3m as recently as 2016.

There is much that is wrong with the world of books. It’s dominated by the privileged and has a daunting amount of ground to make up regarding its

diversity, both racially and in terms of class. But there is much that is right,

too. Events like the one at which Rushdie was appearing earlier this month are an example of what’s good about the industry: occasions where readers and authors can mix and share their passion for books and literature. You won’t find many areas where cultural giants mingle so freely and happily with ordinary people, but I’ve been at literary festivals where some of the biggest names in the business have been found standing at the bar talking long into the night to their readers, or chatting happily at the signing table long after their event has finished. What underpins these events is a bond between authors and readers that’s forged in trust.

Writing is a solitary occupation so events are as important for authors as

they are for readers: it’s the only opportunity for a writer to experience a reaction to their work in the wild, to see for themselves the results of those

long lonely hours in front of the screen. Musicians, actors, professional

sportspeople – they all have access to an instant reaction from their public.

Authors send their work into the world and other than the odd tweet and the

customer reviews section on Amazon the reaction is generally silence.

That’s why live events are vital, especially to an author who for most of the second half of his life has been more detached from his audience than anyone else. For him to be on a stage able to see and hear the reactions of

an audience of people to his work and opinions would have been immensely

important.

That’s what made the images of the aftermath of the attack on Rushdie even more shocking because if he felt safe anywhere it was among book people. Walking down Fifth Avenue, riding on the subway or eating in a restaurant would have induced a far higher sense of threat to his personal safety than stepping on to that stage.

I’m not a Rushdie expert by any means. I’m not even particularly a fan. I’ve read Midnight’s Children, his Booker prize-winning 1981 novel of the partition of India that was also selected as the “Booker of Bookers” to mark the award’s 40th birthday in 2008, but that’s it. I haven’t read The Satanic Verses, and in that, I have a great deal in common with some of Rushdie’s noisier critics including Ayatollah Khomeini himself, but the sight of that crowd of anxious people gathered at the rear of the stage as medics knelt over the stricken author gave me the same cold feeling in my stomach as that experienced by his most dedicated admirers.

As the day went on and it became clear Rushdie was alive, I began to think about how the fact that The Satanic Verses was not only published in the first place but continues to be lauded and stocked in bookshops in the light of fatwa, protests and violent demonstrations says much for a fearless defence of free speech in a literary world often perceived as a bit wishy-washy.

In 1990, a bombing campaign targeted five English bookshops just for stocking The Satanic Verses and the previous year a man had accidentally blown himself up in a Paddington hotel while constructing a bomb intended for Rushdie. In 1993, 37 people died in a fire at a hotel housing attendees and speakers at a Turkish literary festival, a blaze set by a mob looking to kill a writer inside who was working on a Turkish translation of Rushdie’s book.

Yet still, it thrived, even as its author vanished from public view to spend the next decade flitting between safe houses, sometimes as often as twice a week, and will continue to thrive even as Rushdie lies in hospital facing a future much changed by his physical injuries alone, let alone the psychological ones. Whether we’ll ever see Rushdie walk on to a stage in front of an audience again seems unlikely, but given his determination to rise above what he’s been through in the last 33 years you would be ill advised to bet against it.

In the aftermath of the attack I thought about the writers who went before Salman Rushdie, writers physically assailed as a result of their work, many of whom did not survive.

From our continent alone I thought of the Bulgarian poet and novelist Yana Yazova, for example, who wrote beautiful, quietly subversive verse and was found murdered in her Sofia apartment in 1974. Four years later her compatriot, dissident novelist Georgi Markov, was assassinated on Waterloo Bridge with a poisonous pellet administered via the point of an umbrella. I thought of Hugo Bettauer, the Viennese author whose biggest success, 1922’s Die Stadt Ohne Juden, (The City Without Jews), which ruthlessly lampooned antisemitism, saw him shot dead in Vienna in 1925 by a member of the Nazi party, and Isaac Babel, author of the wonderful Odesa Stories, who in 1941 like many of his contemporaries was tried, convicted and executed on trumped-up charges by the Soviet Union.

In particular, I thought of Johann Philipp Palm. In the spring of 1806, he was running a bookshop and small publishing business in a Nuremberg swarming with Napoleon’s troops. Unsurprisingly, anti-Gallic feeling ran high and when Palm published a pamphlet called Deutschland in seiner

tiefsten Erniedrigung, (Germany in its Deep Humiliation), that urged locals to

rise up against the occupiers, it was just one of many in circulation. He was arrested and sent to Braunau-am-Inn in Austria for interrogation and trial where he refused to give up the name of the pamphlet’s author, was found guilty along with other booksellers and publishers from around the region and sentenced to death. When his fellow detainees were pardoned and released, Palm – still refusing to name his author – assumed when his cell door opened on the morning of August 28, 1806 that he too was going home. Instead he was marched in front of a firing squad and killed at the third attempt in a hideously botched execution.

From Palm there’s a direct link to Ettore Capriolo, the Italian translator of The Satanic Verses who was attacked at his Milan home in 1991 by a man

seeking Rushdie’s location and stabbed multiple times when he refused to reveal it. He survived, as did William Nygaard two years later when the Norwegian publisher of Rushdie’s book was shot three times in Oslo.

As Alastair Campbell pointed out in these pages last week, the Rushdie

incident puts the “war on woke” conducted by whingeing snowflakes firmly into perspective. It’s not just the author who should be supported and applauded for his defence of the written word, but those brave enough to stand by his work even at the risk of their own lives. Writers and those associated with their work have been doing it for centuries. May those

chairs on the stage not remain empty for long.