One afternoon in 1934 a boisterous game of ping-pong was in full swing at Southgate House, a stately Georgian pile near Chesterfield, when one of the

combatants inadvertently stood on the ball. A rummage in a nearby cupboard eventually produced a replacement, but the search had been impeded by several old books taking up space better served – in the opinion of the house’s owner Colonel William Butler-Bowdon – by sports equipment.

Returning the next day, Butler-Bowdon began to sort through “an entirely undisciplined clutter of smallish leather-bound books” with a view to disposing of them altogether. It was lucky for us he didn’t. Among the musty, mottled, rodent-nibbled tomes under the badminton nets and croquet mallets was the only surviving copy of one of the most significant works in early English literature.

For hundreds of years scholars had sighed wistfully about The Book of Margery Kempe, the memoir of a Christian mystic from King’s Lynn whose life straddled the turn of the 15th century. Aside from some brief extracts published in 1501 by the pioneering and magnificently named printer Wynkyn de Worde, the book was presumed lost forever until a full handwritten copy, one possibly supervised by Kempe herself, obstructed the denouement of a table tennis encounter half a millennium after it was written.

As well as chronicling its author’s religious visions, The Book of Margery Kempe is regarded as the first English autobiography. Her father was a wealthy local dignitary who was five times mayor of King’s Lynn (known as

Bishop’s Lynn until 1537) and Margery documents how she became well

known around the town for her expensive taste in clothes.

She married John Kempe, whose ineptitude in business meant Margaret had to turn her own hand to industry, establishing first a horse mill, then a brewery, while also somehow finding the time to have 14 children.

The divine visions started after the birth of her first child and developed

into a lifelong conviction that she had been with Christ at his birth and had

remained with him until the resurrection. She took to speaking of her revelations in the streets of Lynn and began to travel widely, first in England, then farther afield: Santiago de Compostela, Prussia, Rome and Jerusalem. She was arrested on suspicion of heresy just about everywhere she went and admitted to being avoided by fellow travellers for her persistent wailing and remarkable ability to burst noisily into tears whenever she thought about the death of Christ. She thought about the death of Christ often; the next outburst of teary caterwauling was never far away.

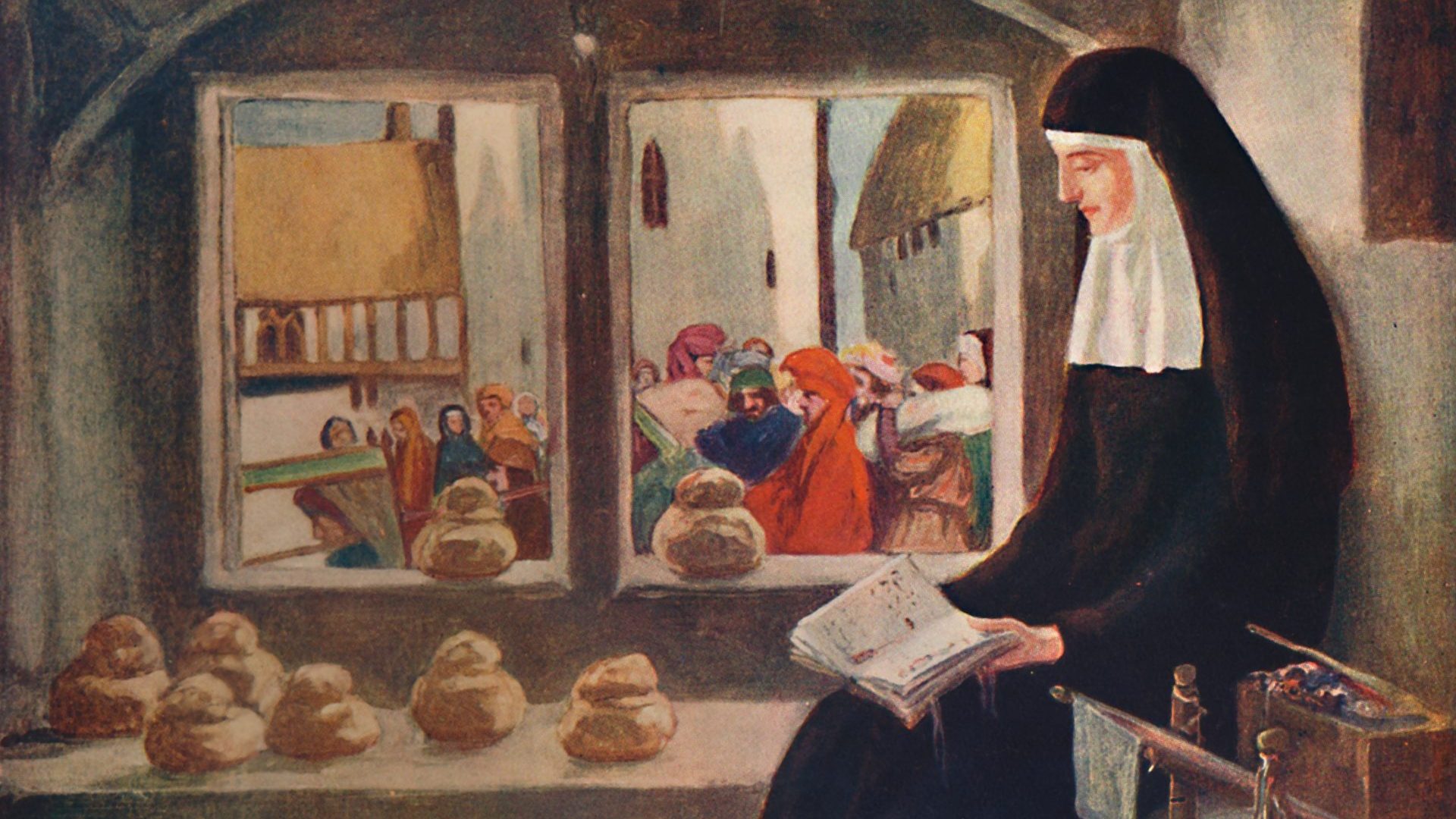

In spite of her religious obsession, what makes Kempe’s memoir so absorbing is the amount of secular detail she includes, conjuring the rhythms and routines of everyday life in medieval England like no work ever before.

Yet perhaps the most exciting aspect of the book, at least for bookish types, is the revelation that she met Julian of Norwich.

Remarkably, the two most significant female authors to emerge in Britain before the birth of Jane Austen were contemporaries living within 50 miles

of each other. While both were famous Christian mystics from Norfolk, however, their lives and circumstances couldn’t have been more different.

Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love details the “shewings” that she experienced, divine visitations during a near-death experience in her late 20s. While Kempe’s visions sent her out into the world on long, noisy, tear-stained pilgrimages, Julian became an anchoress, bricked up for decades inside a small cell attached to a Norwich church, living a life of isolation, prayer and meditation. She wrote two accounts of her visions, a short summary that possibly served as part of an application to become an anchoress, and a longer version written in her cell that contained the famously reassuring repetition: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well”.

Margery travelled to Norwich to meet Julian in or around 1413, at God’s behest, she said, to consult on whether her divine visitations were genuine or the work of the devil. Julian, invisible behind her window, assured her she

was doing God’s work.

The encounter with Julian, and her endorsement, inspired Margery to extend her wanderings beyond the shores of Britain. It also provides the climax to Victoria MacKenzie’s debut novel For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain, a fictional recreation of the two women’s lives that coaxes both from the wispy caverns of myth to become tangible figures as flawed and racked with conflicting emotions as any of us.

Good historical fiction is harder to pull off than you might think. It’s easy

to over-research, to shoehorn so much period detail into the narrative it almost becomes a challenge to locate plot among all the context. Putting

words into your characters’ mouths is a challenge too; the temptation to

spatter dialogue with “thous”, “thees” and “yea, verilys” producing not so

much authentic period diction as cartoonish nonsense.

Fortunately, MacKenzie avoids both pitfalls to produce a concise, tightly written novel that manages to evoke the sights, sounds and smells of the early 15th century. As a result, she achieves the remarkable double success of making both characters at once exotic in their ancient mysticism but

recognisable to the 21st-century reader. The language is determinedly modern but without overtly contemporary idioms and nuance, presenting women of their own time, yet also of ours.

Despite not loading her prose with overwrought evidence of archival ferreting, MacKenzie still conjures the period, for example when a young

Julian hears the thump of bodies tossed on to a cart during the Black Death. Watching from a window, she notes how sometimes the coverings come loose “to reveal a chin or an ear”.

This lightness of historical touch allows in chinks of modern mindset, where divine visitations, lamentations and visions meet postpartum depression and self-harm, not to mention the ever-present scourge of misogyny. When Margery tells her husband of her first vision of Jesus, for example, he scoffs: “Why would he show himself to a woman?” When she requests a couple of hours of her local priest’s time to discuss her experiences, he exclaims: “Bless us! What could a woman have to say about the Lord that could take so long?”

Written in the first-person voices of both women, For Thy Great Pain… stays faithful to Kempe’s memoir but the scant biographical detail we have about Julian allows the author a little more freedom to explore. Julian is holed up in a small cell with three windows, one looking into the church so she can take part in mass, one to allow communication with her maid with a linen curtain pulled across so they can’t see each other, and another looking on to the street where she can observe the world going by.

“Amidst the bustle of this world, it does no harm to have a woman who watches,” she writes.

MacKenzie’s Julian married a man who had taught her to read and write, enabling her to pen her own book while the illiterate Margery employs scribes, but later died of the plague along with their baby daughter. A few years later Julian contracted the plague herself and was on the point of death

when she had her first “shewing”, a manifestation of Jesus himself, followed quickly by 14 more until her fever broke and she began to recover, changed utterly by the experience.

While in her own account Margery can sometimes appear cartoonish, careering through the streets wailing and bawling over the death of Christ and disrupting every church service she attends with ear-splittingly histrionic reactions to sermons and readings, Julian is far more nuanced,

frequently swamped by self-doubt and awareness of her flaws.

“I’d thought I would live as slowly as moss in my stone cell,” she writes of her early days as an anchorite. “I’d thought I would step out of my life, my self, as soon as I stepped into the cell. But I was still me. Nothing had changed. I was myself with all my usual racing thoughts and yearnings and memories and foolishness.”

We flit between the two characters as they chart their lives and the circumstances that brought them together for an encounter that MacKenzie ingeniously delivers in the format of a screenplay, then leave them to their lives. Julian, older than Margery, has not long to live. Margery embarks on the next stage of her devotion, a series of long overseas pilgrimages.

For Thy Great Pain… is more than just a wonderful piece of historical

fiction, it’s a nuanced exploration of religious conviction, mental illness, misogyny and the legacy of grief. The contrasting figures of Kempe and Julian give MacKenzie rich material to work with, but she still manages to

elevate these remarkable women and their extraordinary lives to a level that

has so much to say to us in even these secular times.

Oh, one last thing: let’s be sure to raise a glass to that stray table tennis

ball and the galumphing size eight that flattened it.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria MacKenzie is published by Bloomsbury on 19 January, price £14.99