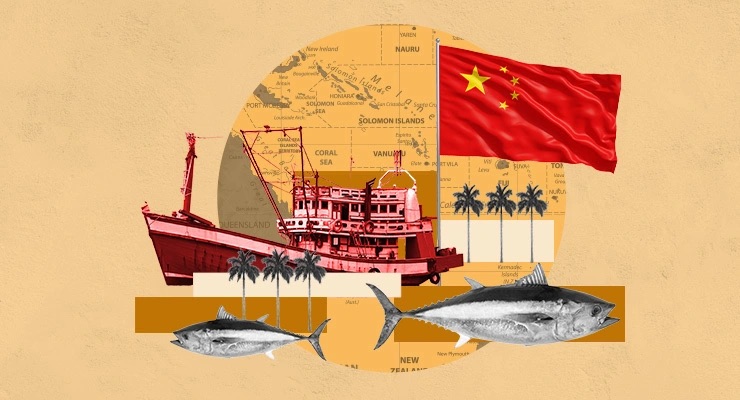

China’s looming security deal with the Solomon Islands is about much more than the simple expansion of its military footprint. A key plank in Beijing’s strategic goals is food security. In terms of the Pacific, that means fish.

In 2013 Chinese leader Xi Jinping emboldened Chinese fishermen to “build bigger ships and venture even farther and catch bigger fish”, leading to the accelerated expansion of the country’s global fishing fleet.

The global seafood industry has more than quadrupled in the past 50 years. China consumes between 35-45% of the world’s seafood according to various estimates.

China’s demand has been forecast to triple between 2020 and 2030 due to rising demand for protein and a domestic focus on seafood as the source for this.

The country is leading the damaging global trend of distant-water fishing (DWF) that too often takes place in the territorial waters of low-income, defence-poor nations, such as Australia’s neighbours in South-East Asia and most especially the South Pacific.

The 14 sovereign nations and seven territories of the South Pacific have a combined population of less than 13 million people and account for more than 15% of the world’s surface. Only 4km separate Australia’s Boigu Island in the Torres Strait and Papua New Guinea, although it is 150km between the mainlands of the two countries. Approximately 2000km separates Australia and Vanuatu.

In recent years, China has inked major deals to build ports for fishing with both those nations, first in 2018 in Vanuatu and then in late 2020 in Daru, the Papua New Guinea town closest to Australia.

China is not the only country engaged in industrial-scale DWF but it is by far the biggest (Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and Russia are the next largest offenders in that order).

The People’s Republic of China’s fleet is the world’s most extensive: 2701 in 2019 according to official government numbers. But the London-based Overseas Development Institute estimates that China has 17,000 vessels deployed in DWF operations. In comparison, in 1985, its very first distant-water fleet was comprised of 13 fishing boats.

DWF is closely associated with unsustainable levels of fishing and so-called illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities. Unsurprisingly China is also the major player in this arena, accounting for as much as one-third of the world’s annual catch.

China’s activities — and other DWF — are doing untold damage to the world’s fish stocks and are major contributors to the destruction of marine ecosystems, which in turn is a major contributor to climate change. In 2018, the United Nations noted that 90% of the world’s fishing grounds were depleted.

Fish stocks in the South China Sea — many of its waters the subject of disputes between China and its South-East Asian neighbours — are already so depleted that now the Chinese DWF is looking farther afield, including in Australian waters which are already being targeted by Indonesian fleets and others.

China is building a string of DWF bases on its coastline, including in Fujian, Shandong, and Zhejiang provinces. The latest is a US$64 million facility in the city of Zhuhai that neighbours Macau, which is to be completed in 2024. It is being built by Zhuhai East Port Xing Ocean Fishing Co., a fishing firm with vessels in Vanuatu — a Pacific nation that has drawn closer to China in recent years.

Chinese fishing vessels regularly encroach on Australian waters in what is known as the “grey zone”.

Australia is at least alive to the problem in the Pacific and is a long-standing supporter of sustainable Pacific fisheries, as well as an active member of, and donor to, the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency ($5 million annually) and the Pacific Community ($2.4 million annually).

“Australia is also implementing additional programs to help our regional partners tackle illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, including coordinated engagement under Australia’s $2 billion Pacific Maritime Security Program,” according to the Department of Foreign Affairs.

Australia is actively working with Pacific nations to extend its official reach into the region’s vast fishing grounds. But China appears, as with the Solomon Islands deal, to be a step ahead.

At a meeting of the first China-Pacific Island Countries Fishery Cooperation and Development Forum, held in Guangzhou on Dec 8, 2021, Ma Youxiang, the vice minister of fisheries at China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, said China stood ready to cooperate on finding solutions to problems related to IUU fishing, proposing the establishment of an “intergovernmental multilateral fishery consultation mechanism”.

To be fair, China leads the world in aquaculture, accounting for 58% of the world’s output. But its demand for seafood is a key driver behind its growing presence in the Pacific and elsewhere in the region.

This piece was originally published by Crikey.