The pressures of wartime leadership are taking a toll on the ageing autocratic leaders of Russia and Belarus. There are rumours that Putin has numerous ailments including Parkinson’s and cancer. It is alleged that everywhere Putin goes he is accompanied by a team of doctors.

Belarus’ leader Alexander Lukashenko did not speak as he usually does at the annual Day of the National Flag and National Emblem event on 14 May due to a suspected illness. Rumours of illnesses have been fuelling other rumours. There are claims that the Kremlin is using pre-recorded footage of Putin giving the impression he is working when he is actually incapacitated. There are also claims that Putin is using a series of body doubles to attend events in his place. Whilst some of the reporting about the health of these leaders may reveal more about the hopes of western commentators, the potential use of doubles reveals more about the paranoia of these leaders and some deeper truths about the nature of power in these societies.

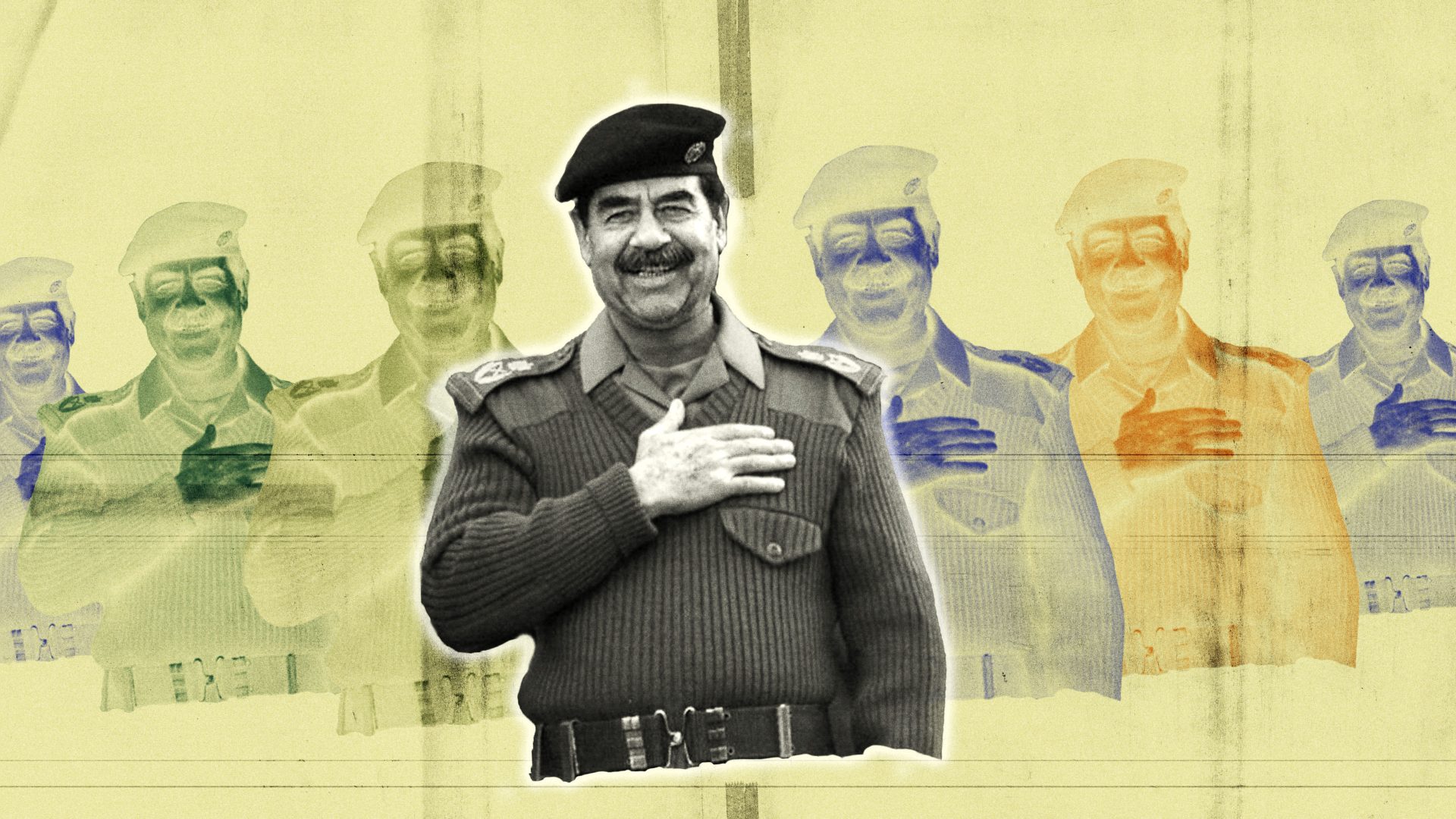

The use of doubles is not uncommon amongst despots. North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un is said to use multiple doubles and was once caught on camera chatting to one of them. On return from periods of absence, due to a variety of health issues, the footage of his appearances are scrutinised. His hairline, and teeth are compared to previous images to determine whether it is really him. There have been multiple claims that Iraq’s former president Saddam Hussein used doubles. In a book that was turned into a film, former soldier, Latif Yahia, claimed to be a double for Saddam’s son Uday. Latif claimed that he was summoned from the Iran Iraq War because Uday remembered how similar they looked when they were at school together. He claims to have undergone surgery to increase the resemblance.

The use of doubles for both Saddam and Uday has been questioned. Ala Bashir, Saddam’s physician claimed, “neither I nor any of my fellow plastic surgeons in Iraq have had anything to do with altering someone’s face to look like the President”. After highlighting inconsistencies in Latif’s story in an interview, Latif’s ex-wife said she thought his claims were “dubious.” The journalist Ed Caesar interviewed one confidante of Uday who told him that Latif was arrested for impersonation of Uday. Another claimed that he pretended to be Uday to pick up women.

The Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov addressed the rumour that Putin was using doubles while he hides in a bunker, “You see yourselves what our president is like: he always was, and is now, mega-active – those who work next to him can hardly keep up with him… Of course, he doesn’t sit in any bunkers.” Despite Peskov’s statement there are many who don’t believe that the Putin who carried out a surprise visit in March to Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine was really Putin. Anton Gerashchenko, of the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs, posted three images of Putin’s chin questioning how they could all be the same person. Major General Kyrylo Budanov from Ukrainian military intelligence suggested last year that Putin’s ears looked different in several appearances.

There is precedent for the use of doubles by Russian leaders. Boris Yeltsin was rumoured to have a double when he was recovering from a heart operation. Joseph Stalin is alleged to have had a double, known only as “Rashid.” Rashid claimed there were other doubles employed by the KGB, although he never met any. In 2008 another one of Stalin’s doubles, Felix Dadaev, came forward. Putin gave him permission to tell his story and he appeared in a documentary about Stalin’s last days.

The possibilities of using doubles to create deception have also been exploited by democracies. General Montgomery, commander of Allied ground forces during Operation Overlord, used a British soldier named M. E. Clifton James as his double. James learnt Monty’s gestures, gait and voice and because he had lost a finger, was given a prosthetic one to wear. James was sent to North Africa to distract the Germans from the invasion planning the real Monty was doing in Europe.

The CIA, as part of its plan to bring down Indonesia’s president Sukarno in the 1950s, used a double to portray him in a pornographic film having sex with a female Soviet agent. The humiliation was supposed to drive Sukarno from office. Instead Sukarno found it amusing and asked for additional copies.

Outside the activities of intelligence agencies though the use of doubles is concentrated amongst autocratic regimes. There are similarities between Putin, Kim Jong-Un, Saddam and Stalin’s regimes that explain why this is so.

In these regimes state power is concentrated, not in democratic institutions and processes, or even a single political party, but in the body of one man. This partly explains our fascination with the health of that one body. In these states, the opposition is repressed and the independence of state institutions, the judiciary and the media is removed. When all political options to remove these autocrats are removed the only way to end the repression is to physically remove the body in which all power rests. Leaders like Putin know this, which leads them to have a healthy paranoia of being assassinated.

Saddam was subject to a number of assassination attempts including an Israeli plan in 1992.

After the murder of prominent party member, Sergey Kirov, Stalin became increasingly concerned by the threat of assassination and rarely went out in public. The Russian government (dubiously) claims that the drone attack on the Kremlin in May was the sixth attempt to assassinate Putin. The use of body doubles by leaders fearful of attempts on their life allows them to mitigate this risk, sending the doubles out to face the sniper’s bullet or the assassin’s poison.

As well as providing security for autocratic leaders, doubles can fulfil a duty that many despots find potentially tiresome: meeting the masses. Discussing Fyodor Antonov’s painting, “Comrade Stalin with Railroad Craftsmen in Tbilisi”, the artist David King claimed that the painting could be ignored as bad art were it not for the chronic misrepresentation of its message. In reality, Stalin was isolated from ordinary workers, never visiting factories nor collective farms. The performance of doubles, alongside misleading images, can give the impression that far-removed leaders are close to their people.

Putin portrays himself as being driven by the concerns of ordinary people as well as an historic destiny to restore the pride of the motherland. Keeping his physical distance, he hosts an annual phone-in where he fields answers to calls, video messages and texts (all tightly controlled by officials). During these he promises to help with problems besetting ordinary citizens from supplying a village with gas to sorting out an individual’s unpaid pension.

But all this can serve another purpose. Autocrats want to insert their image into the everyday lives of their citizens without actually having to meet those citizens. Many autocrats put their mark on their countries by building statues not just as an act of self-apotheosis, but also as part of a system of psychological surveillance. When they cannot physically be everywhere at all times, and even teams of doubles cannot achieve that feat, statues are used as a simulacrum of the actual body. Paintings and photographic portraits of leaders hang in every public building. Putin is omnipresent, not only across the airwaves of Russia’s media and in every government building, but also on the magnets, mugs and matryoshka dolls sold in souvenir stalls throughout his hometown of St Petersburg and other Russian cities. As with the show elections that keep him in power, Putin’s autocracy creates an illusion of choice, which rests on the silent threat of punishment for disloyalty.

As autocratic regimes end, when the people cannot get hold of the actual body of the leader it is the symbolic body in the form of statues that get toppled. Saddam had thousands of portraits, posters, and statues erected all over Iraq. One of the iconic images of his fall, while Saddam himself was still on the run, was the toppling of his statue in Firdos Square, Baghdad. Long after dictators are buried in the ground the process of pulling down their image can continue.

When autocratic regimes do not end in violence, but expire as the autocrat’s body expires, there is the question of what to do with the body. After Lenin died in 1924, the Soviet diplomat Leonid Krasin proposed a monument containing his corpse that would become a centre of pilgrimage. Krasin also attempted – unsuccessfully – to cryogenically freeze his body. After eventually being embalmed and placed in the mausoleum in Red Square, Lenin’s body has been well cared for. His suit was replaced every 18 months. After a makeover in 2004 it was announced that he looked younger than he had done in decades. His tomb remains open today. Visitors are required to show respect: photography and filming are forbidden, as is talking and keeping hands in pockets. An embalmed Stalin joined Lenin after he died in 1953. In 1956, his successor, Nikitia Khrushchev, delivered a speech denouncing Stalin’s personality cult, and his dictatorship. A process of demolishing Stalin’s statues all over the USSR began shortly after, but it was not until 1961 that his physical body was removed from public view.

The treatment of Lenin and Stalin’s bodies highlight another similarity between these autocratic regimes: there is no limit to the number of their citizens they will sacrifice for their own ambitions. As fears of his own assassination peaked after the assassination of Kirov, Stalin launched the Great Terror. The purges, mainly conducted by his secret police (NKVD), began with the removal of the party leadership and government officials, and expanded to every corner of Soviet society. The NKVD used imprisonment, torture, and arbitrary executions to exert control through fear. Saddam sacrificed hundreds of thousands of his soldiers in the invasions of Iran and Kuwait, as well as conducting his own purges. Saddam’s regime brought about the deaths of at least 250,000 Iraqis. As well as the mysterious deaths of oligarchs and political rivals, we are also seeing in the “meat grinder” of Bakhmut and other Ukrainian cities that Putin is equally happy to sacrifice the bodies of others to achieve his ambitions. Even in death Lenin’s body was seen as more valuable than those of ordinary citizens. When Nazi forces were approaching Moscow in 1941 his body was evacuated to safety before any of the city’s living inhabitants. In countries where doubles are used, ultimately only one body matters. There is no number of other bodies that can be sacrificed, to save the one, starting with the doubles sent out to meet the assassins and restive masses.

Thomas Hobbes, the original theorist of state power, saw the essence of power as state sovereignty. Hobbes thought that at its best and purest power would be exercised from the singular position of sovereignty. He called it “The Leviathan.” More recent work has focused on the distributed nature of power in modern Western states. To understand autocratic regimes, particularly those in Russia, Hobbes’ theories – based on a powerful sovereign – remain the most useful. The Soviet regime which began as a revolt against the sovereignty of the Tsar, could best be understood under Stalin as a continuation of Tsarism, when the despotic nature of his regime became clear. Putin compares himself to Tsar Peter the Great.

Hobbes’ fundamental principle of human nature is that each of us is in a relentless quest for domination over others, in a “war of all against all”. We are each seeking only to further our own ability to have the power to do what we like and avoid doing what we don’t. This is a recipe for endless conflict, driven by competition, distrust and the attainment of glory or status. In this state it can be rational to kill others before they kill you. Hobbes’ solution to the question of how we should govern is to put a powerful individual or parliament in charge; the Leviathan. He argues that, motivated by their strongest passions – the fear of violent death and their desire for a comfortable and pleasurable life – individuals must enter a social contract with the state. In doing so they give up some freedoms in exchange for security. They agree to allow the state to exercise power of punishment over them and other individuals if they break this contract. While Stalin and Saddam both regularly broke their contract with many who did nothing to challenge their power, purely to instil fear in others or to punish particular ethnic groups, Putin remains relatively popular despite his repressive regime because he has kept his side of the contract. The war in Ukraine, especially conscription and increasing activity impacting the Russian side of the border, is only now threatening his ability to do so.

The Leviathan is referenced in several of the books of the Hebrew Bible. Across the myths in which it appears it is an embodiment of chaos whose annihilation results in a new world of peace. Except in reality when, in autocratic states with no history of strong institutions, the embodiment of autocratic power is removed, Hobbes’ war of all against all is unleashed. As was the case at the end of Tsarism which led to the brutal Russian civil war and in Iraq after the removal of Saddam. We should remember this every time the subject of regime change is raised.

The embodiment of power in a single individual results in an underinvestment in the democratic institutions of state. When power sits within institutions rather than the body of one man, there is little need for leaders to employ body doubles. No matter how much semi-naked horseback riding and judo you do, the body ages and ills. Immortality is as out of reach now as it was for those looking to freeze Lenin. But, our institutions can also whither and they can be deliberately eroded. When we focus on the body of the leader rather than the institutions, when cults develop around certain politicians and leaders and their followers believe they are more important than these institutions, we take tentative steps down a path to autocracy.

While we obsess over the health of despots and are maybe even amused by the paranoia that leads them to employ body doubles of sometimes questionable standards, we should be reminded that these are symptoms of brutal systems of governance. We should be wary of our own egotistical leaders, who promote their own personality cults over our institutions. Because it is these institutions that protect us from the autocrats – and like any leader, they can fail, and disappear.