NOBODY WANTS THEM

Wherever he went, Abdul Saboor was beaten. As he tried to walk to freedom from his violent homeland, he was detained in Pakistan, beaten and repatriated. He was assaulted in Iran and imprisoned for months. In Bulgaria, the beating came with a side dish of pepper spray in the eyes. In Serbia, he froze in a filthy refugee camp. If caught taking photographs, he was hit some more. Saboor’s trek from Afghanistan to western Europe was painful and demeaning.

At home, he had worked for Nato and the United States. The resurgent Taliban saw him as helping their mortal enemy and shot him. The third time, he spent 10 days in hospital with a bullet in the back. He had to leave. His American employers didn’t help.

His journey took two years. He stayed a while in Bulgaria, but seeking asylum wasn’t an option – they sent Afghans back home to danger. He ended up in France. The beatings became rarer, he said; in the West, they beat you up mentally.

“The Taliban says ‘you should die’. People in Europe say the same: stay in your country – and die,” he tells me on the phone from Paris. Until now gregarious and talkative, his voice falls to a whisper. “At home, people called me Abdul. On my journey, I was ‘Afghan’. Now they call me ‘refugee’. I’m not Abdul any more.”

As we spoke, his brothers made the same journey, escaping the new Taliban threat. His mother stayed behind – she wouldn’t have survived.

Five years after he first set out, overcoming reams of bureaucracy and multiple interviews, Saboor has refugee status in France. He takes haunting photographs of refugees stuck in squalid camps in France, hoping to cross the Channel for a safer life. Some of the British newspaper pictures of the people who drowned last November were his.

There are many like him, fleeing for their lives from war or failed states – to whose failure the West may have contributed, such as Afghanistan. “People forget their history,” Saboor laments. “They forget who joined the fight, who sold the arms.”

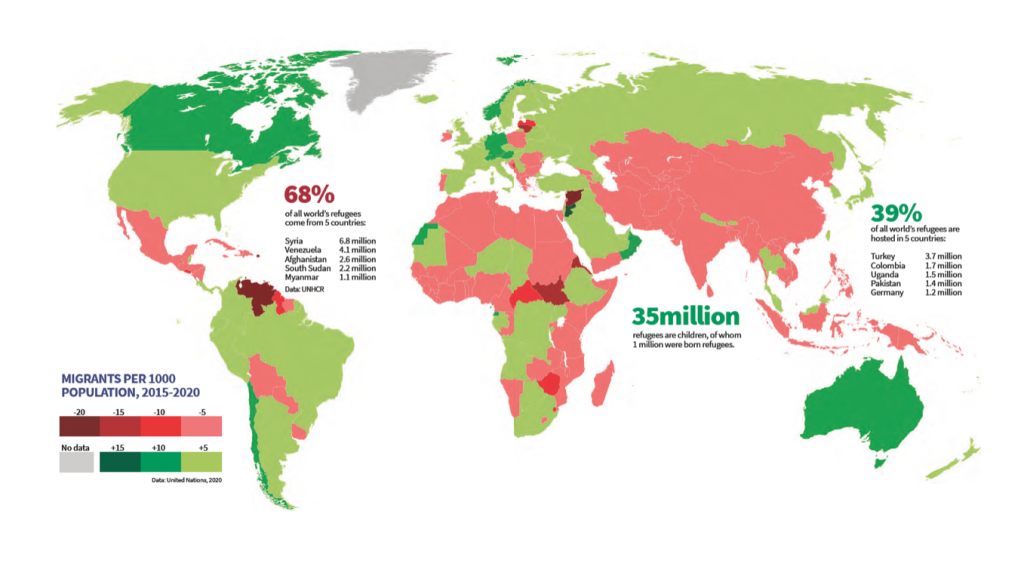

Currently, there are over 84 million forcibly displaced people in the world, including 26 million refugees, according to the United Nations’ refugee agency, UNHCR. Yet, contrary to the breastbeating of Nigel Farage, the Daily Mail and the current British government, they rarely trouble the UK’s shores. Those making the dangerous and all-too visible cross-Channel journey in rickety dinghies last year may be coming in record numbers, but last year’s 28,431 arrivals are low in the scheme of things.

Asylum claims are less than half what they were 20 years ago. Per capita, 15 other European countries receive more. The majority of refugees who get to France do not cross the Channel. On any objective scale, there is no “migrant crisis” in the UK.

Nor is there one, especially, in the European Union. Numbers are nowhere near where they were during the peak of the Syria crisis seven years ago, when they were anyway a fraction of overall asylum seekers worldwide.

But the fact that we think there is stems from another crisis of a particularly pernicious kind – a plague of populist politicians.

“Politicians are very good at frightening people – you know, an invasion of migrants, they’ll take your jobs away from you,” Dawn Chatty, Emeritus Professor in Anthropology and Forced Migration at Oxford University, told me.

“The numbers aren’t necessarily rising hugely. What’s happening is that more and more states in the global North are simply not fulfilling their obligations under the 1951 [Geneva Refugee] Convention.”

The main treaty for refugee protection, the Geneva Convention represents international standards for governments to step in and ensure the safety of anyone whose states are unable or unwilling to protect their fundamental human rights.

But humanitarian experts worry that many of its nearly 150 signatories seem to have forgotten its contents. Compliance is voluntary. With no punitive oversight, there is nothing to make them remember.

Alongside the grip of populist mythology comes a crisis of compassion with fatal consequences, as outlined by Gordon Brown last month: “How can it be that, in these first weeks of 2022, the world is allowing millions of Afghan children to face death from starvation?

“Countries are locked into the narrow nationalism of ‘America first’, ‘Britain first’, ‘China first’, ‘Russia first’, ‘my tribe first’ … a geopolitics that puts military and economic sanctions before food for the hungry,” Brown wrote. “Our liberal world order is proving itself neither liberal nor orderly.”

HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?

Squeamishness towards refugees, and migrants of all sorts, is not new. Even apparently tolerant politicians are obsessed, especially when the optics turn sour.

“It’s absurd that most meetings they’ve been having in Downing Street have been about the Channel crossings,” said Enver Solomon, head of the Refugee Council of Britain. “But I was recently reading a book on Blair’s period in office in the early 2000s, after the Iraq war, and most meetings then were about the Sangatte camp [in France] – history is repeating itself.”

At the time, thousands of asylum seekers from Iraq, Afghanistan and the Balkans were parked in the sprawling refugee camp in Calais, trying to get to Britain. Under pressure from the Labour government, France closed it in 2002.

“Almost nine out of 10 refugees will not get anywhere near Europe. They will mostly stay in neighbouring countries,” Solomon said. “What’s happening is that there is a prevailing political anxiety around being seen to be too soft on the issue.”

Critics often ask of refugees coming from the Middle East – why don’t they go to a Muslim country? Well, they do.

Turkey, with a population comparable to Germany and suffering its worst economic downturn for two decades, has nearly four million refugees who fled the civil war in neighbouring Syria; more than any other country. At least two million more live in Jordan and Lebanon – where half the local population is below the poverty line amid an economic and political crisis.

After Turkey, the biggest refugee host countries are Colombia (population 51 million – 1.7 million Venezuelans fleeing political and economic crises); Uganda (among the poorest countries in the world – over 1.5 million mostly from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo); Pakistan (1.4 million registered Afghan refugees); and Germany (the only developed country in the top five – 1.2 million, mostly Syrians).

In Asia, around 850,000 Rohingya Muslims – whose explosive story of genocide in Myanmar in 2017 became yesterday’s news – crowd in prison-like camps in Bangladesh.

More than half of all refugees are children. That’s why they keep turning up at borders. Like Saboor, born a refugee in Pakistan, many millions of children grow up in camps. Sometimes they’re the only ones left alive in their families, but are treated with suspicion. Britain closed down its short-lived programme – proposed by former child refugee Lord Dubs – for unaccompanied children.

Women and girls are as likely to be refugees as men, but less likely to travel to Europe as for them the journey has the added danger of rape and sexual assault. The lack of safe routes in effect discriminates against women.

After the Syrian crisis, thousands of refugees, including Afghans and Iraqis, returned home from “nightmarish” Europe, where they felt humiliated by anti-immigrant attitudes and struggled with cultural differences and poor job prospects. Some Afghans were pictured kissing the airport tarmac with relief.

Harsh anti-migrant policies from one country led to copycat behaviour elsewhere. Even normally refugee-friendly countries such as Sweden became prey to the ascendant right. As have others in Scandinavia. Germany, where at one point border police let refugees stream in from Hungary with the words “you are welcome here”, faced a backlash.

This panic is cynically stirred by others, most recently when Belarus invited and encouraged asylum seekers in to try and cross its border with Poland and destabilise the EU from there. Poland decided to build a frontier wall. Other EU countries argued for something similar.

Faced with one of the biggest humanitarian crises of a generation, Europe had looked in on itself and come up with all the wrong answers. European countries could have built a coordinated, comprehensive, effective and humane asylum policy to ease their collective burden and make refugees safer. The lesson learned was not how to protect people, but how to keep them out.

Suddenly, everybody wanted to be Australia.

BAD SHIT

In the past decade, Canberra developed a particularly pitiless asylum system.

Arrivals are detained immediately and indefinitely, without access to regular judicial intervention. In 2012 it began “offshoring” them to remote locations in the Pacific Ocean, such as Papua New Guinea (PNG) or Nauru, for processing. Boats carrying asylum seekers are pushed back.

The Australian model has been condemned by human rights lawyers as illegal, but the tiny numbers now seeking entry to Australia are held up as proof that it works. A talisman for governments elsewhere struggling to show they’re tough enough on what they call “illegal migration”.

January’s Novak Djokovic debacle gave just a glimpse of the horrors. Before he was deported for breaching Australia’s strict Covid border policy, the unvaccinated tennis star was detained in a Melbourne hotel where asylum seekers had been trapped for years. Denounced as a “torture cell” where maggot-ridden food had made residents sick, the facility described as filthy by Djokovic’s mother wasn’t close to being the worst hospitality to unwanted arrivals Australia has to offer.

The facilities in PNG and Nauru have been called “Guantánamo of the Pacific”. Detainees, including babies, children, disabled and sick people have been found to be suffering from off-the-scale levels of trauma, depression and anxiety.

Médecins Sans Frontières said in 2018 that suffering in Nauru was the worst it had seen, including among victims of torture. Some of those held brutally and endlessly have rioted and self-harmed, others killed themselves in despair. A five-year-old attempted suicide.

“For many, Australia is a democratic country but for refugees, it is a dictatorship system. Refugees are unprotected by the law and at the same time victims of the law,” tweeted Kurdish-Iranian editor Behrouz Boochani – who spent six years detained on PNG’s Manus Island.

“Some say that Australia’s reputation has been damaged because of the situation with [Djokovic], but in a better world, public anxieties about international image would be stirred by the imprisonment of refugees in the same hotel for a decade.”

One of those was Mehdi Ali, now 24, who tweeted: “I’ve served more time than rapists, but I’ve never committed a crime in my whole life. My ‘crime’ was asking this country for safety.” The man, in detention since he was 15, was asked by international media not about his plight but for his views on Djokovic.

Australia’s immigration policy is so cruel that even China criticises it as a way to divert attention from its own dismal human rights record.

Yet the British home secretary, Priti Patel, is a fan. The country seems to have become a post-Brexit role model for the UK on several levels.

With her government under pressure to make good the Brexit promise to “take back control of our borders”, Patel’s statements have become increasingly hyperbolic. The extreme rhetoric of “clamping down” on and “smashing” this migration has become the calling card of a government seemingly hell-bent on shutting the door on mercy.

It has created an arms race of supposed remedies, which have grown in eccentricity. Paraded in the media have been ideas of using wave machines to push dinghies back; employing the navy to combat a few dozen individuals clinging to a leaky inflatable; shipping all asylum seekers to Albania/Ascension Island/Rwanda/ Ghana/disused oil platforms/warships to be processed; sending civil servants on jet skis to intercept refugees in boats; giving asylum seekers electronic tags and age-checking child migrants with X-rays or teeth examinations.

Most of these gems were never really on the table, as they are unworkable, expensive, inhumane, or all three. They have been much sneered at, but Australia demonstrates that the central premise of shunting refugees back out to sea or spiriting them to the ends of the earth is not a figment of Patel’s imagination.

Currently legislation is being prepared to put meat on the bones of these hardline aspirations, with the Nationality and Borders Bill – called the “anti-refugee bill” by humanitarian workers. Tightening entry requirements and refusing to consider arrivals by sea, in effect it criminalises asylum.

The refusal to equitably distribute refugees across Europe put enormous pressure on its border countries: Spain, Malta, Cyprus, Italy and Greece. As asylum seekers flocked to its shores while the rest of the EU demanded it stop them, a desperate Athens resorted to detention – supposedly a last resort – as the norm.

Supported by Brussels, it built expensive new “closed” camps, with sports facilities, restaurants and air-conditioned rooms for vulnerable people. A welcome improvement on the squalid, muddy conditions of the older facilities – if only they weren’t enclosed by military-grade fencing and watched over by police. Now, they sound like prisons and encapsulate the dystopian vision of what is fast becoming “Fortress Europe”.

Greece became a buffer zone after Angela Merkel cut a deal in 2015 with Turkey’s President, Tayyip Erdoğan, to keep refugees out of the EU in exchange for money and visa relaxation, which never happened.

This trend was predicted as far back as the 1990s. Canadian-American academic James Hathaway, a leading authority on international refugee law, warned that the global North would end up outsourcing refugees to the global South.

Writing in the Cornell International Law Journal in 1993, Hathaway also warned that increased European integration could devalue refugee protection – tough external borders and tight visa regimes would be needed to allow freedom of movement within.

Europeans had come to see “foreigners” as threats to regional stability and security, he wrote, which would be “devastating for refugees”.

Migrants from the less developed world would be seen as “an undifferentiated evil: refugees, economic migrants, drug traffickers, and terrorists are officially categorised as presenting a unified threat.” Regardless of human rights principles in law, refugees would be treated as “presumptively unworthy of protection”. Thirty years later, this sounds all too familiar.

Turkey largely kept its side of the bargain in terms of hosting refugees, but it is wearying of its role. Its once porous Syrian border is now lined with fencing and trigger-happy guards.

More hidden, and more troublesome, have been successive European agreements with Libya. Fed up with the financial and public relations toll of dealing with Sub-Saharan migrants, the EU wants them stopped before they even reach European waters.

According to refugee groups, the militia-linked Libyan Coastguard now patrols the Mediterranean, obstructs humanitarian rescue, captures migrants and detains them, sometimes for years, in abusive environments run for a tidy profit. There are reports of torture with electric shocks, guards raping children, extortion and detainees sold into forced labour.

A former Libyan minister for justice, Salah Marghani, told a New Yorker investigation the aim was to create a hellhole in Libya to deter migrants and “make Libya the bad guy. Make Libya the disguise for their policies while the good humans of Europe say they are offering money to help make this hellish system safer.” Niger, one of the gateways for migrants going through Libya to the Mediterranean, was encouraged to curtail its previously relaxed border policy.

In this way, brutal militia are becoming de facto border guards of a bloc, the EU, whose leaders claim is the most tolerant and humanitarian in the world. The continent that created the Geneva Convention, whose central pillar is “non-refoulement” – you can’t send someone back to danger. It’s a principle the countries in the West, with their border agreements and repatriation obsessions, are coming perilously close to breaking on a regular basis.

Susan Akram, international human rights law director at Boston University School of Law, says Washington similarly pressures countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras to prevent their citizens from leaving, and pays Mexico to take harsh measures to stop them entering the US under its Migration Protection Protocols and related policies. Separately, its prevention through deterrence policy forces asylum seekers and migrants to cross through areas where authorities know they’re likely to die.

The numbers trying to reach East Asia – by sea or otherwise – are modest by comparison with Europe, and the doors are shut even tighter. Japan and South Korea, two of the richest economies in the world, have very restrictive asylum policies and demand a high burden of proof. Both were late signatories to the Geneva Convention. Japan, which helped Belarussian sprinter Krystsina Tsimanouskaya seek refuge during last year’s Tokyo Olympics, has long been one of the largest donors to international humanitarian organisations. The UNHCR’s first female high commissioner, Sadako Ogata, was Japanese. But her country lags way behind its peers on resettlement. In 2020, Japan, a country of 126 million, granted refugee status to only 47 applicants. In 2013 the number was six.

South Korea’s President, Moon Jae-in, is the son of refugees from North Korea, and accepts tens of thousands of defectors from there with little fuss. But the arrival of 550 Yemeni refugees in 2018 caused an outcry, and the nearly 400 Afghans transported to South Korea last year after the Taliban takeover were snuck in as “persons of special merit” to avoid a public backlash.

Seoul has only granted refugee status to around 1.5% of all applicants in the past 25 years, according to justice ministry figures (this does not include North Koreans), and cites the European chaos after the Syrian crisis as justification.

Both Asian powerhouses have had detention scandals. Last year a 33-year-old Sri Lankan woman, sick and starving, died while awaiting her asylum decision in Japan, while South Koreans were shocked by footage of a Moroccon asylum seeker masked, with his hands and feet bound, struggling to move in a tiny, filthy detention cell.

In 2020, South Korean officials were found to have falsified, mistranslated, incorrectly recorded or omitted testimony from nearly 2,000 asylum seekers with the apparent intent of rejecting their claims.

Apart from contributing to serial human rights breaches, such policies simply don’t work: the cost is often higher than allowing refugees in.

Australia’s offshoring policy cost the country £4.4 billion between 2014 and 2020, according to the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law. Australia stopped sending new arrivals to remote islands in 2014 because the policy failed, but the 200 or so who remain in offshore detention are expected to cost it nearly a billion Australian dollars a year.

Offshore detention didn’t deter the boats – but pushback did, when Australia broke international law by forcing boats to turn away, or putting asylum seekers on lifeboats with just enough fuel to get to Indonesia.

“It’s deeply concerning that any country would consider trying to replicate what Australia has done in terms of offshore processing,” Madeline Gleeson, senior research associate at Kaldor, told the House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee last year. “It was not effective in achieving its policy goal, and on top of that the legal and humanitarian concerns with this policy should be cause for great pause … for any state that considers itself a democratic society based on respect for common decency.”

Rationalising the effect of refugees in a country is hard and dependent on government response to avoid employers exploiting the low-skilled and pushing down wages. But several studies by organisations such as Deloittes have found that they are generally young, literate and entrepreneurial, and, in the long term, boost job numbers.

A HISTORY OF PLAYING NICE

To understand how to move forward, it is necessary to look back. Although refugees have a troubled history, precedents for good practice are also there.

Although all Britain seems to want now is to bolt the doors, it has a long history of taking in refugees, such as the Protestant Huguenots from France in the 17th century and Russian Jews in the 19th. Between 1914 and 1917, nearly a quarter of a million undocumented Belgians fled a German invasion and came here.

After the second world war, the new UNHCR, envisaged as a temporary agency, sent many displaced people from Europe to countries that could use their skills, including the US, Chile, Uruguay and Canada.

In 1956, 200,000 Hungarians fled their country following a brutal Soviet suppression of pro-democracy protests. In what became one of the most successful examples of solidarity in the face of forced migration, within three years, 180,000 of them were resettled from Austria and Yugoslavia to 37 mainly European countries. A public outcry forced a reluctant US to take 80,000 refugees.

It took much longer to help the nearly one million so-called Vietnamese boat people who fled pro-US South Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975. In an uncomfortable echo of today, many perished in the seas, with South-East Asian countries unwilling to take the survivors. In the end, UN official Sérgio Vieira de Mello oversaw a comprehensive plan to distribute most of the refugees around the world, while securing safe passage home for those who felt they could return. This kind of solution is required today.

Mello also helped to deal with the fallout from the Balkan wars, when nearly two and a half million refugees fled inter-ethnic genocide in the heart of Europe. They found safety in several countries and many returned once the Dayton peace accords were signed in 1995 and their homes were safe. It was another good example of the West helping to alleviate a problem.

One of the latest waves to touch the West, which continues today through the instability and conflict in parts of the Middle East, started following the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq – although the country really imploded from 2006, when civil war broke out after the international coalition mismanaged the rebuilding of the country. Even then, most stayed close to home.

Not every politician or journalist fans the flames. There is also a regular flow of heart-rending human stories, but whether these change minds, simply inure the readers to pity or inflame easily triggered anti-refugee sentiment is unclear.

IS ANYBODY LISTENING?

Yet among the gloom, examples of good practice emerge.

Germany’s generosity during the Syrian crisis comes up regularly. Armed with the lessons of the largely ignored, patchily-integrated Turks who had come to work there in the 1960s and 1970s, Germany put in place strong integration programmes, which included vocational training, mandatory language lessons, fast-track work permits and financial incentives for company traineeships or the Syrians. It found that these refugees started to pay back as new taxpayers after three years, not the originally envisaged five. Despite the rise of anti-immigrant populists, German voters put social democrats and leftist Greens in government.

Sweden may have hardened its policies, but it also has visas you can apply for in other countries, which cuts out bullying traffickers and dangerous journeys.

African states, with their enormous refugee camps, are innovating. Uganda, low on political freedoms, is widely praised as one of the world’s most progressive refugee-hosting countries. Unusually, it allows refugees the right to work and freedom of movement, meaning they can cultivate under-populated plots of land, both supporting themselves and benefiting the host community.

The normally more restrictive Kenya has just opened a new refugee camp along the lines of the Uganda model, encouraging self-reliance, entrepreneurship, agriculture and a market place for refugees. Ethiopia has pledged to grant the right to work and free movement, support job creation and build industrial zones where both refugees and Ethiopian nationals can work.

US President Joe Biden may have his troubles softening Donald Trump’s immigration policy, but he has announced that the US will resettle a record-high 200,000 refugees this year – a stark change from his predecessor’s 10,000-odd.

While the US was pulling back, Canada stepped up, and in the year before the pandemic resettled more refugees than any other country. Canada has pioneered private sponsorship of refugees and community involvement to the extent that its successful model is being spread out across other countries.

In fact, one common thread throughout my research interviews was a trend for an increased civil society role, as individuals and groups take matters into their own hands.

“Volunteerism has emerged. I call this the anthropology of the good. It’s tremendous!” Chatty told me, citing people who bring blankets and food to greet the boats from France, and volunteers for the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, which consistently upholds international laws to save people at sea, regardless of their own political views or the UK government stance on refugees.

While the Faragists parade around the British coast, trying to stop lifeboats from leaving for rescue missions (as per one viral video last year), NGOs work on helping child refugees to integrate, many of them still traumatised from their experiences. “I worked with a couple of boys who had seen their friends blown to pieces in front of them,” Bridget Chapman, of the Kent Refugee Action Network, told me. “They come here with awful memories. We have to gently help them move on and adjust to a new life.” This includes education and life skills we might take for granted. Having never seen a microwave, one boy put a metal spoon in his and blew it up.

In Italy – whose current prime minister, Mario Draghi, called refugees a much-needed resource to help compensate for Italy’s ultra-low birth rate – proactive local leaders in poorer southern regions have been resettling groups of refugees in empty villages that would otherwise lose schools and services, reversing their gradual population declines.

Pioneers for this project include Domenico Lucano, who as mayor of the medieval hilltop town of Riace set up a government-funded scheme to offer refugees abandoned apartments in what was becoming a ghost town. They received training in dying arts such as traditional pottery and helped to rebuild Riace’s population and its economy. In 2016 he was named one of Fortune magazine’s 50 greatest leaders, putting him in the company of Pope Francis and Canada’s Justin Trudeau.

“This policy gave the village a new lease of life, it didn’t trigger any wars between the poor, or xenophobic hysteria or fraudulent speculations. It helped to give new values to the people involved,” Lucano said. His case is complex, however, and under the far-right interior minister Matteo Salvini, Lucano was jailed for a string of convictions including arranging marriages of convenience for migrants, and other crimes to facilitate illegal immigration.

Nevertheless, plans for similar schemes are under way in Spain, which has long worried about its own emptying and depopulating areas. Spain has about 14 inhabitants per square kilometre in 70% of its territory and, according to one estimate, more than 4,000 villages in rural Spain are dying out.

Boston University’s Susan Akram is currently in Spain’s Murcia region helping to prepare a pilot resettlement project with Spanish partners including the well-established NGO Fundación Cepaim that works all across Spain with migrants and asylum seekers. The pilot is planned in four or five areas where Cepaim has already been working. Akram told me the plan aimed to seek investment from two diverse EU funding streams – for refugees and underdeveloped communities – to create a special legal pathway to sponsor refugees the local communities themselves believe would fit in and contribute, such as farmers and their families, entrepreneurs of small businesses, dairy farmers, teachers, olive oil and wine producers.

“In a documentary about rural Spain, I saw these beautiful stone houses that were falling apart, and it reminded me of Syria and Palestine,” she said. “I thought, Syrians and Palestinians know how to rebuild those.” There is a history of Arab culture in the south-eastern coastal region where Muslims had settled between the 8th and the 15th centuries. The terrain and produce would also be familiar. “The Syrian landscape reminds me so much of the Murcia olive tree … and the crops are similar – pomegranates, artichokes, grapes.”

Further case studies include Norway, where researchers have found that when refugees are distributed around a country, rather than grouped together in urban centres, integration and sustainability is greater.

In the UK, I am involved with one of the small but growing number of community resettlement projects, overseen by the Home Office as a branch of the UNHCR vulnerable refugee resettlement programme. I came across Hani Arnaout, a Syrian refugee in the village of Ottery St Mary, who has become a model of what happens when things go right. Now a pillar of the community, he loves his new calm, countryside home so much he called his daughter Mary.

Directly involving locals also creates the power of contact and generates sympathy. It’s a powerful tool to challenge all the negative messaging. Even so, individual actions cannot be enough. Worldwide, resettlement requirements for the most vulnerable are at record highs, offers to resettle are catastrophically low.

Vincent Cochetel, UNHCR’s special envoy to the Mediterranean, said: “We estimate that about 1.4 million people are in need of resettlement. We know only that 100,000 will be resettled every year, because that’s the sort of quota we have from various resettlement countries. So selection is very difficult.”

BUT IF THE SYSTEM IS BROKEN?

UNHCR resettlement is essential and should grow. But it’s no silver bullet. It only covers extremely vulnerable people who have invariably spent years, maybe decades, in camps or communities within the scope of the UN programmes. Many people in great danger or need don’t tick those boxes. In the absence of alternatives, it has been criticised for being discriminatory and hierarchical — often used by governments publicly helping flavour-of-the-month refugees while ignoring others. In the summer, it was the Afghans. Before that, refugees from elsewhere felt overlooked in favour of the Syrians.

The UK embraced the scheme at the height of the Syrian crisis. While refusing to join a putative EU redistributing scheme, David Cameron’s government signed up to UNHCR resettlement in an apparent outburst of humanity after newspapers ran images of a Turkish policeman carrying the limp body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi along the beach near where he drowned, featured to devastating effect on the front page of The Independent newspaper, edited at the time by the BBC’s Amol Rajan.

But country or crisis-specific refugee plans have led to a stop-go approach, which means that time, money and expertise lost when schemes are closed cannot always be recouped.

When Trump crippled the US programme, he dismantled systems and lost experienced staff with decades’ worth of knowledge and experience.

In the UK, Refugee Action’s Louise Calver explained that difficult-to-source housing was lost when the Syrian refugee programme was closed during the pandemic. When refugee groups leave the rental market, other tenants step in. Thousands of evacuated Afghans are still stuck in tourist hotels at great government expense while they wait. Children go to school from their hotel rooms, deprived of the stability to recover, build their lives, create social bonds.

“It’s one of the worst ways for mobilising a response,” Calver said. “Globally there’s a pattern of ongoing conflict. So why not embed proper safe routes, fundamentally review the commitment to resettlement and build a system that meets the scale of the problem and our resources?”

One comprehensive system that works, is scalable and doesn’t waste money – which would be spent on refugees instead – would be vastly preferable to today’s piecemeal approach.

The same goes for the asylum system. Resettled refugees can slowly start work, but in many places asylum seekers find their right to work restricted. In the UK, they must live on an allowance of nearly £6 a day for 12 months, after which they can apply for a limited selection of jobs. Full access to the labour market is withheld until refugee status is confirmed, which could take years.

Solomon told me he believed Sajid Javid was close to granting refugees the right to work when he left the Home Office. The idea that Priti Patel will extend this lifeline seems remote. Yet Germany’s refugees can seek work four months after they arrive, because authorities think that’s how long it takes for them to recover from the trauma of their journeys and start to trust people again.

Before that, they need safe pathways to claim asylum – and alternatives to dangerous road and sea routes are often discussed, rarely created.

Special humanitarian corridors, humanitarian visas secured from embassies, and more outside-the-box thinking – such as getting the British border guards working in places like the Gare du Nord in Paris to help screen asylum seekers before providing papers for those with strong claims – are among ideas that could help.

Improved family reunion policies (although the British government is seeking to restrict these) and a less rigid visa programme might have allowed some of the people who died in the Channel in November to reach their relatives in Britain without losing their lives.

But even with positive adjustments like this, the overall situation is quite possibly beyond repair.

TOTAL SYSTEM FAILURE

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) believes the entire system is broken as international humanitarian arrangements fall apart.

There are currently 55 civil wars raging around the world – more than at any time since the second world war, says Harlem Désir, IRC’s senior vice-president in Europe. Diplomacy is failing. A record low number of peace deals were signed last year, because it’s hard to negotiate an ending when so many wars are internationalised, involving several foreign actors, from governments to armed rebels.

The UN is ill-equipped to help. With global power fragmenting, fractious UN Security Council members veto anything they feel is international interference – a tactic that affects peacekeeping, monitoring and sanctions. This means more refugees are created and the means to help them are limited.

Conflict monitors are disbanded, aid is blocked and middle-sized countries ignore global conventions. Attempts to find a way out of this mess are hindered by a blind, unexamined and outdated reverence of sovereignty. The concept is being used to undermine human rights and hide from accountability by countries both democratic and autocratic on the notion that states should have unlimited powers within their borders. The phrase Take Back Control is laden with that sentiment.

Aid can’t fill this gap. Developed countries are ignoring the target to spend 0.7% of their GDP on international development. With the pandemic as an excuse, Britain cut its target to 0.5%.

Less than half of humanitarian needs are funded, Désir says: “And we have seen the consequences of aid cuts in several places, including where the most traumatic situation is ongoing, like in north-west Syria.”

There have been calls for the UN to be more active and powerful, with the Security Council veto suspended in cases of mass atrocities so that infighting can’t prevent intervention.

Whether or not the UN springs to life, many other problems remain. Alexander Betts, head of Oxford University’s Refugee Studies Centre, sees human displacement as one of the defining challenges of the century – one that needs strong political will that is currently absent.

“What we see is more and more countries rejecting asylum seekers and challenging the 1951 Convention – there are many examples,” Betts tells me.

Asylum and immigration have become scapegoat issues, he says. Western countries could accommodate more refugees, but unless politicians deciding to do this take the public with them, they risk a backlash that can undermine the whole process. With societies deeply polarised, most don’t even try.

They argue the opposite – that to stop the deaths, they must make the country unattractive and eliminate “pull factors”. That is, don’t be nice or everyone will come.

The logic here is flawed because it doesn’t take into account the complex factors behind displacement. It’s true that some asylum seekers do have a rosy view of the West, and those already resettled may embellish their quality of life on social media – it’s embarrassing to send bad news home.

But people don’t put themselves in the hands of dangerous traffickers for fun. Mostly, they’re displaced by “push factors” – violence is raging, their states fail, people are persecuted, their countries can’t guarantee their human rights, natural disasters or climate make their countries unviable.

These factors grow and change, and start to intertwine. There’s even debate about whether the Geneva Convention is fit for purpose.

Climate change, for instance, is not officially a reason for asylum. But it is increasing poverty, instability and human movement. It fuels tension and competition for increasingly scarce resources. Since the countries affected so far are also poor, war-ravaged, authoritarian and economically bust, it’s hard to pinpoint one single reason to flee. But 90% of UNHCR-recognised refugees come from countries on the front line of the climate emergency, from Burkina Faso and Bangladesh to Mozambique, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi.

Developed countries should reflect upon how climate change is a phenomenon fuelled largely by consumption in the global North and which is being inadequately tackled by those very same states stuck in a complacent, short-termist loop.

Failing and dysfunctional states are also producing more of what are often denigrated as economic migrants – a byword for “bogus refugees” framed as gaming the system for easy gain.

Yet the world is full of uncontroversial economic migrants – both within and without their own borders. They’re called expats, or praised for “getting on their bikes” to seek work.

Whatever they’re called, people who can’t live in their own countries in dignity, feed their families, find work or reskill need to move, too.

“Our economy needs legal migration so we have to open those pathways,” Couchetel said. “If Europe had more legal channels for economic migrants as well as for refugees to seek protection I think it would be easier to have a good dialogue with the country of origin to return those who are not in need of protection.”

Should the Geneva Convention be rewritten to define new categories? In today’s political climate, the more likely result of opening it up for renegotiation would be to narrow, not widen, its scope.

Betts said: “We need some basis on which to discern who has a human right-based claim to cross an international border in a dramatically changed world.” In the short term, the best option would be to consolidate some guiding principles based on refugee, human rights and humanitarian law that identify how states should respond to people displaced by environmental and other contemporary reasons.

NO WAY OUT?

There are examples and precedents of institutions in the West doing the right thing, as shown after the second world war and in Bosnia. New non-biding documents are beginning to incorporate climate change into the concept of asylum. The European Parliament is looking at a common humanitarian visa system, while the UNHCR is piloting skills-based migration pathways. But much more is needed.

The Refugee Council’s Solomon likened overseeing refugee protection to fighting global warming and emphasised the need to deal with both in an international, coordinated way. This is exactly what isn’t happening now – in either case.

It’s hard to see how attitudes will change until the narrative does. Refugees don’t, on the whole, steal jobs or harm the public. They can be very well (often over) qualified, hard-working, eager to learn, grateful for the chance, and can contribute. As western populations age and start to shrink, they will need them.

If employers are using refugee and immigrant workers to illegally undercut wages, it’s not because these people are here, but because the state isn’t enforcing its own rules.

It’s important these issues, real and imagined, are addressed since, as always, it’s the economy, stupid. Unlike those fleeing around the time of the two world wars, today’s refugees are overwhelmingly from poor countries, even if they are themselves not necessarily poor. Global inequality fuels migration of all kinds.

For a successful migratiopn policy, one that is both humane and economically and politically palatable, governments, international institutions and the private sector have to join forces to create a culture of empathy and appreciation of the benefits that accrue when migration strategy is focused on reality rather than fear.

Ultimately, if governments want to end their “migrant crises”, the solution doesn’t lie in spilling them back into the sea and hoping one day so many will die that even violent persecution at home becomes preferable.

Dialling down the visuals, the rhetoric and the panic-mongering while quietly getting on with the job of cooperating on aid, encouraging private sector help, designing a good, safety-first asylum system – and seriously seeking ways to enable people across the world to live in peace and dignity: that would help more than generating absurd scare stories about jetskis.