That the home secretary used the word “invasion” on the floor of the Commons while talking about migration was no slip of the tongue. Neither was it something said in the heat of the moment.

She was using the language of a juggernaut that, despite a few bumps in the road, is still picking up speed: the populist right. And signalling that the person in charge of immigration to the UK has the populist right’s back, Suella Braverman is onside.

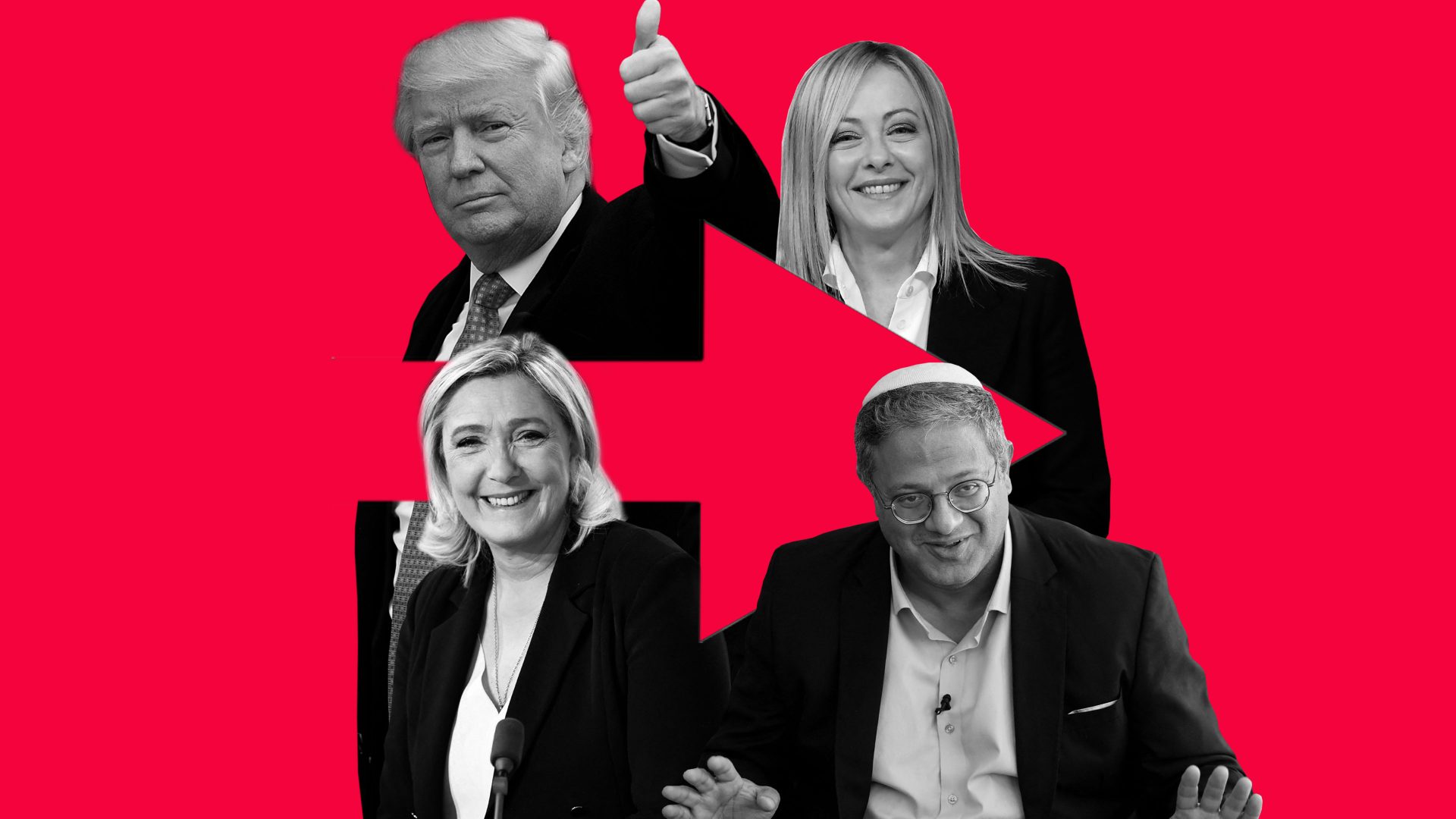

This populist right encompasses everyone from new Italian PM Giorgia Meloni, whose Fratelli d’Italia party – the Brothers of Italy – are eager to play down their birth as Mussolini sympathisers, to Itamar Ben-Gvir, the far-right extremist leader of Jewish Power, a guy who once waved a gun around on the floor of the Knesset and who now is the kingmaker for Benjamin Netanyahu’s return as prime minister.

The populist right openly addresses fear: the fear of change in all of its political manifestations. It is also deeply nostalgic. In Britain, Boris Johnson cleverly invoked, in almost everything he said, a faux past.

This past, consciously and unconsciously, centres around the myth that Britain single-handedly won the second world war. This nonsense is fuelled by its biggest cheerleaders: those male WWII vets who weren’t old enough to see WWII at all, having been born from the late 1950s to the mid ’70s.

One of the triumphs of the British populist right, achieved only by the skin of its teeth, was Brexit. This was sold on the premise of “Make Britain Great Again”. Its subtext was a covert and increasingly overt sense of loss.

When people feel that the way things used to be is being eroded, they follow the leader who can make it OK again, a template that has been successful in the past.

And Ground Zero for populism is grievance, and fear. The fear is that something is being taken away. The grievance is that a controlling elite is out there, in cahoots with those elusive “outside forces.” The Tories use the tag “North London” as a way to identify these enemies within.

The populist right also seems to prefer strongmen as leaders to take them back to the sacred time of The Way It Used To Be. They loathe the “normal” leaders of western democracies – Joe Biden, Justin Trudeau, Emmanuel Macron – and view their falling poll ratings as the ultimate failure of the democracy of the elite.

From Italy to Sweden and beyond, a large part of the body politic is turning to candidates who will roll back this elite. Roll back change itself.

Boris Johnson campaigned in 2019 on a kind of “Make Britain Great Again”, an apparent change agenda that was really an anti-change agenda.

He invoked a Finest Hour trope in which the UK – which to him and his supporters means England – stood “alone” against the Nazi hordes and used it to insist that the nation would prosper if it turned its back on its nearest neighbours. That Churchill himself never expressed this idea, even advocating what he called a kind of “United States of Europe”, is airbrushed out of the scenario of populist right rhetoric.

Marine Le Pen won more votes this time around than she did the last time; and in a twist to the usual demographic of the populist right, Netanyahu is going into coalition with a racist party in a country where the young are more conservative and right wing than their elders.

Another aspect of the populist right is that they perceive the world as becoming increasingly restrictive, especially in regard to free speech. The populist right makes freedom of speech one of its central appeals, a freedom of speech in which it is OK to call people whatever you want and treat them however you like.

“Freedom of speech” is a battle cry of the popular right. Another is “displacement”, the fear that, for now, dare not speak its name.

In America, this fear is called “The Great Replacement”. It is the fear of the right-wing white population, that they will be eventually swamped by people of colour; by people who speak another language; eat other kinds of food. The populist right sees the younger generation, most especially those in their mid-thirties and below, a diverse generation, as a particular threat.

Donald Trump has changed his slogan from “Make America Great Again” to “Save America” and, of course, he is the only one who can save it.

He embodies that other element of the populist right: the transgressive politician. The one who says the unsayable; who metaphorically puts his feet up on the desks of the establishment. This transgressive politician breaks the barriers of politeness; spits in the eye of the politically correct and gives an outlet to those who feel that the world is slipping away from them.

Another example is Michael Gove, who once insisted that Britain had had enough of experts; and Kwasi Kwarteng, who fired the civil servant who headed up the Treasury, taking the reins himself with disastrous results; and back again to Boris Johnson who said that as for the parties that went on during lockdown, he would do it all over again.

These people who would have once, at the very least, been chastised, are now seen as heroes of a kind of incivility; sayers of that which was once The Unspoken. No one can predict the outcome of what is, without doubt, a new age. This age is full of uncertainty; and when it comes to stating fear of that uncertainty, the populist right says it out loud.

This year is the centenary of TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, his mighty dissection of the time past and the one to come. In it the poet writes:

That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?