Volodymyr Zelensky knows how to press historical buttons. When addressing the US Congress, the Ukrainian president referred to Pearl Harbor and 9/11. When talking to the House of Commons, he inevitably invoked Winston Churchill. He even summons “what if?” moments, asking the Canadian parliament to envisage bombs falling on the cities of Toronto and Vancouver.

Of course, when it came to the Germans – the country he is most frustrated with – he talked of the second world war. And the Berlin Wall, repeatedly.

His most intriguing reference was to the Soviets’ blockade of the western half of the city and the Allied airlift that relieved it.

For Zelensky to succeed in repelling this next phase of his country’s invasion, Ukraine will need not only new weapons but new supplies of food, medicines and other humanitarian aid. Think Berlin 1948, think Mariupol, Kharkiv and other Ukrainian cities now.

As the division of Germany was being formalised, three years after Hitler’s capitulation, the Americans, helped by the British and the French, came to the aid of a surrounded enclave. They did so in the full knowledge that it could lead to a further war, possibly a nuclear one, but they felt they had no choice. Had they done nothing, West Berlin would have been starved into submission. It would eventually have folded into the Kremlin’s orbit.

The Warsaw Pact would not have had a very public hole in its heart, advertising liberal democracy. Then what? One of the many great counter-factual questions of 20th-century history.

Unlike Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Berlin Blockade was not advertised in advance. It was introduced so gradually that the West was initially unaware of what was happening. Traffic delays and diversions were increasing, but in those early postwar years, Germans had seen far worse.

The first hint came in March 1948, when the Soviet Chief of Staff accused western powers of assisting illegal traffic into the city; four days later he announced steps to protect citizens against “subversive and terrorist elements”. Shortly after, the Russians pulled out of the four-country Allied Control Council. Western nationals travelling to Berlin on the Autobahn and by rail would be required to show ID and submit to searches. The Kremlin ratcheted up the pressure, step by step.

The Americans countered by posting soldiers on trains. The Russians backed down. A month later, cars on the main transit routes from Frankfurt and Hamburg were blocked by barricades. A British transport jet approaching the airfield in the UK’s zone was buzzed by a Soviet fighter jet, whose pilot misjudged his path, smashing into the plane, killing himself and 14 others.

The western allies knew they were outnumbered. The Americans had only 6,500 troops in Berlin, indeed by then only 60,000 in the whole of Europe. Stalin had 300 divisions (more than 400,000 troops) within striking distance of the city. On April 13, General Lucius Clay, the US commander, sent a telegram to his bosses in Washington: “We are convinced that our remaining in Berlin is essential to our prestige in Germany and in Europe. Whether for good or bad, it has become a symbol of the American intent.”

The final straw for the Russians was the announcement on June 23 1948 of currency reform by the West German government in Bonn. The Americans were quietly against it but did not stop the finance minister, Ludwig Erhard. The introduction of the D-Mark provided the underpinning for the Wirtschaftswunder, the economic miracle. At the same time, it cemented the division of the two Germanies, and enraged Moscow.

The next day the Soviets announced that the motorway bridge on the Elbe River needed “urgent repairs”. Within hours they had closed off all roads, canal and rail links into West Berlin. The city had only six weeks’ supplies of food and coal. Electric power, which had been supplied to West Berlin by plants inside the Soviet Zone, was cut off; fresh food from the surrounding countryside was suddenly unavailable.

The Four-Power status of Berlin, hastily agreed by the Allied victors in 1945, had omitted to include formal provisions regarding road and rail transit. Access had been based on trust. The deal had, however, established three air corridors from West Germany to the city.

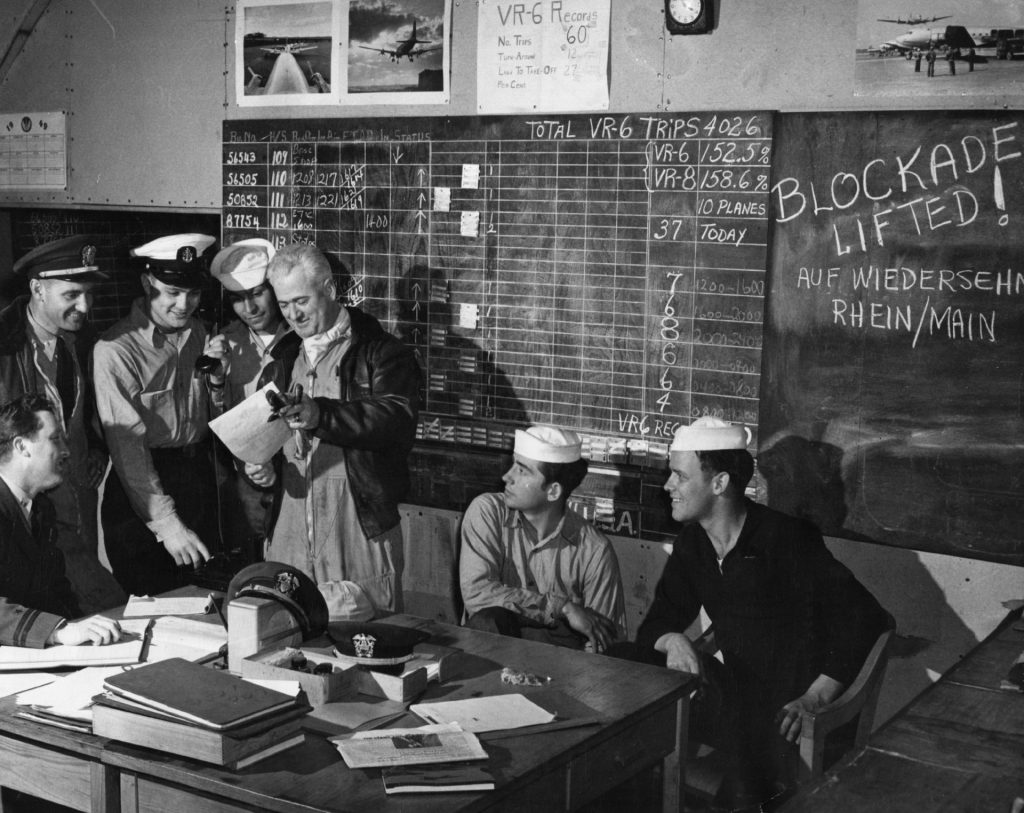

The three western powers acted swiftly: the first plane landed at Tempelhof airport two days after the start of the blockade. An airlift of unprecedented dimensions was organised to supply the 2.5 million inhabitants of the western sectors of Berlin with what they needed to survive.

Around 230 US and 150 British planes were deployed; 17 American and eight British aircraft were lost. Combat-ready fighters went eye-to-eye with the Soviets on a number of occasions.

Up to 10,000 tons of supplies were flown in daily, including coal and other heating fuels for the winter. Altogether, about 275,000 flights succeeded in keeping West Berliners alive for nearly a year.

The Soviets finally relented. We know the rest. West Berlin was free again. The Berlin Wall was built in 1961 to stem the haemorrhage of East Germans using the island city as a means of escape to the West. The Wall, and the system, came triumphantly and peacefully down 28 years later.

Where I live in Berlin, I am constantly reminded of that extraordinary demonstration of hard power in the service of liberal democracy. My local U-Bahn (Underground) station is called Airlift Square and is on the northern edge of Tempelhof. Next to it is a memorial and the remains of an airport that epitomises the idiosyncrasy of Berlin and the contradictions so often at the heart of German reflections of the war and division.

Tempelhof was once the most important airport in the world, the place where the Humboldt balloon was launched in 1893, where Nazi rallies were staged, where Albert Speer planned a grandiose gateway to a new “Germania”.

The last three aeroplanes flew out in November 2008, a month after the airport’s official closure. From that point on, they didn’t know what to do with an area one and a half times as big as the principality of Monaco. It is now a tatty mess, a huge outdoor area for skateboarders, picnickers, kite fliers, even – so the story goes – a man grazing a sheep. Part of it is also a refugee centre.

Whenever the city launches a consultation to develop it, it is rejected.

It is the good Germany and the complacent, childish Germany rolled into one. If transferred to the modern day, would the Allies have launched such a fiendishly difficult operation? After all, the German government itself seemingly wasn’t that fussed. The first chancellor of the new West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, had little time for Berlin. Though an ardent transatlantic and anti-communist, he described Berlin and the surrounding state of Brandenburg as “the Asiatic steppe”.

Many Berliners, particularly older ones, remember the airlift with gratitude. A major thoroughfare is named after Clay. Monuments to the blockade abound. But – and this is the point that Zelensky makes – Germans struggle to translate the lessons of the airlift and other moments during the cold war into a contemporary context – the requirement to take similar military risks for a greater good. And that means not relying on others to do the hard work for them.

Germans’ Vergangenheitsbewältigung, the coming to terms with the past, has inculcated a passion for doing the right thing. That has produced one of the most earnest democracies in the world (think Donald Trump, Brexit, Marine Le Pen); a passion for internationalism, environmentalism and a resistance to the rougher edges of free market economics.

It has also embedded an aversion to all forms of military action. No aspiring politician with any knowledge of public opinion would talk about modernising the Bundeswehr or paying more for defence. Olaf Scholz’s announcement of €100bn (£84bn) for the armed forces and a pledge, finally, to meet the Nato target of spending 2% on defence, as a proportion of GDP, was hailed (not least by himself) as a Zeitenwende, an epoch change.

Since then he has reverted to type, refusing to ship heavy weaponry to Ukraine, incurring the wrath of Zelensky, many across Europe and an increasing number in his own country.

He and several generations of Germans have had it drummed into them that peace is society’s highest calling. The notion of a just war is an alien concept. To which I inevitably inquire whether Auschwitz was liberated by soldiers or a peace movement. It was the military that saved Germany from itself, and then saved Berlin from an enemy that surrounded them and hoped to grind them into submission.

Just like now, only a few thousand miles away.