What, if anything, does the name “Arcturus” mean to you? No, it is not a new social media app, a reformed 1970s prog rock group, or a villainous force in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

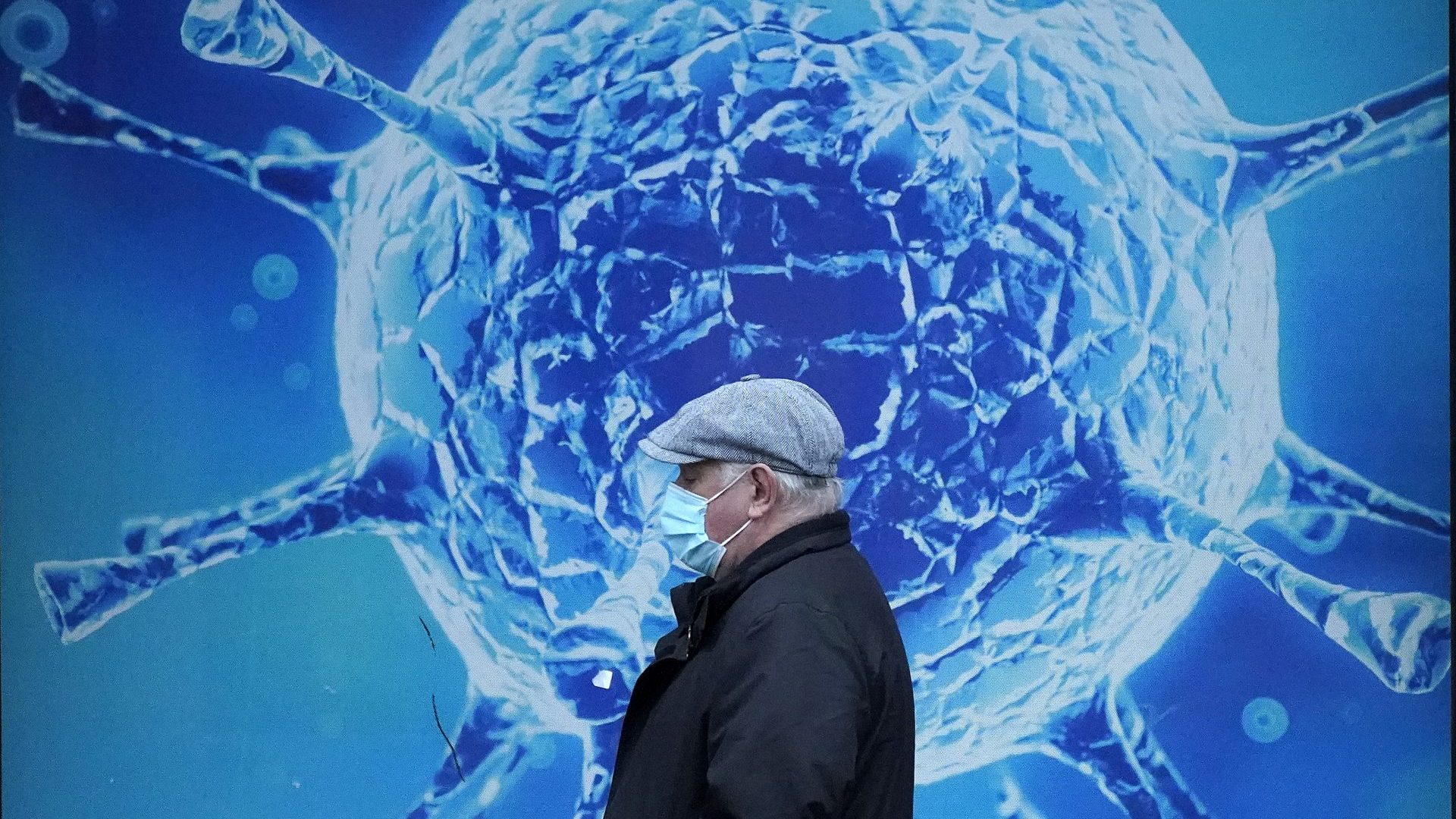

First identified in January, Arcturus – or XBB.1.16, its full epidemiological classification – is the latest variant of Covid-19; which, having surged across India, has now been detected in more than 30 countries. Though it does not appear to be significantly more dangerous than Omicron, of which it is a sub-variant, its emergence is a sharp reminder that the pathogen is still mutating.

Why does this matter? Because a virus that continues to shape-shift is still capable of “vaccine escape”: which means, at some point soon, a fresh round of adapted boosters may be needed to protect present levels of immunity. We cannot afford to drop our guard.

There is, of course, a natural urge to do precisely that. Wilful amnesia is often a by-product of trauma, individual or collective. And a trauma the pandemic most certainly was.

For perspective: according to the government’s coronavirus dashboard, around 227,000 fatalities have been recorded to date with Covid listed on the death certificate. Compare this with the 454,000 British soldiers and civilians killed in the second world war – twice the toll of the virus, but over six years rather than three.

The human cost of the pandemic was colossal, which is precisely why there is an impulse to forget about it. On May 5, the World Health Organization declared that the global health emergency was over. Time to move on, surely?

That has certainly been humanity’s inclination in the past. As Laura Spinney writes in her definitive history of the 1918 pandemic, the millions of deaths from Spanish flu, so soon after the carnage of the first world war, became the “dark matter of the universe, so intimate and familiar as not to be spoken about”.

In truth, that option is closed to us in 2023, not least because Lady Hallett’s official Covid inquiry is already under way and will start taking oral evidence on June 13. This phase of the investigation is expected to last until at least the summer of 2026. Inescapably, given the broad remit of the inquiry, it will be a long haul.

What matters is the spirit in which Hallett’s work is observed by media and public alike, and the impact that it makes upon the national consciousness. At present, and to a dismal extent, that work is being reported exclusively as a subset of the Westminster soap opera; and, specifically, of the tensions between Rishi Sunak and Boris Johnson.

Furious that the Cabinet Office has referred to the police a series of alleged new lockdown breaches, the former PM has handed over a cache of unredacted WhatsApp messages to the inquiry – calculating, it appears, that he has less to lose than Sunak, who has a general election to fight and a reputation to defend.

In retaliation, the government has threatened to withdraw public subsidy of Johnson’s legal costs and – extraordinarily – is seeking judicial review over Hallett’s order to release the former PM’s messages, diaries and notebooks.

While Sunak is in the US this week, he might reflect upon the fate of Richard Nixon, whose reluctance to hand over the Oval Office tapes to Congress as it investigated Watergate led to the articles of impeachment that forced the president’s resignation in August 1974. For a prime minister who promised “integrity, professionalism and accountability”, to make himself so vulnerable to the charge of cover-up is political madness.

It is absolutely right that the inquiry should identify those individuals, procedures and institutions that failed during the pandemic, and that its audit of what went wrong (test and trace, care homes policy, lockdown timing, PPE shortages, and so much else) should be both meticulous and rigorous. Public confidence in its findings demands nothing less. Those who were bereaved – so justifiably furious over the “Partygate” scandal and all that it symbolised – are entitled to the basic justice of comprehensive disclosure and judgment.

Yet, as enormous a task as this is, it represents only half of the inquiry’s remit. Its second core objective is to “[i]dentify the lessons to be learned… to inform preparations for future pandemics across the UK”.

Right now, those preparations are in a wretched state. In April, Sir John Bell, Regius professor of medicine at Oxford, wrote in the Independent that it is “a question of when, not if, another pandemic strikes” – and that “we are not ready”. Far from strengthening our defences against the next such outbreak, much of the infrastructure developed during the Covid crisis is being quietly dismantled or defunded.

After three years, the Office for National Statistics Covid survey has been shut down. Many lab facilities have already been mothballed.

As public spending is squeezed, the all-important RECOVERY trial, researching Covid therapies, is relying increasingly upon philanthropy.

The UK Vaccine Manufacturing and Innovation Centre has been sold off.

The Joint Vaccine Taskforce – much the most successful agency during the pandemic – has been absorbed into the UK Health Security Agency. As Dame Kate Bingham, former head of the taskforce, said in November: “I am beginning to think it is deliberate government policy not to invest and not to support the sector.”

Instead of greater resilience, one detects precisely the opposite. As Simon Schama puts it in his masterly new book, Foreign Bodies, on pandemics and vaccines: “This moment in world history is no less fraught for being so depressingly familiar: the immemorial conflict between ‘is’ and ‘ought’; between short-term power plays and long-term security; between the habits of immediate gratification and the prospering of future generations.”

This is what truly counts – so much more than the daily round of Westminster recrimination and desperate Tory faction-fighting. The highest form of justice is to limit the chance of recurrence. At stake is nothing less than what we owe to our descendants. Will they forgive us?