A light breeze salted the Brighton seafront when the taxi carrying Patrick Magee pulled up outside the Grand Hotel.

It was just after noon on September 15 1984, and it felt like the last day of summer. Sunshine burned through a residue of clouds, warming the pebbles on the beach. The English Channel glistened, serene. The Grand soared over King’s Road like an overstuffed wedding cake, eight stories of eaves, cornices, and Victorian elaboration coated cream and white. A union jack fluttered from the roof. Built for aristocrats, it had hosted kings and presidents and film stars. Soon it would host Margaret Thatcher – and Magee had come to kill her.

The squawk of gulls competed with the tinkle of fairground music. It was a Saturday and Brighton was a town at play.

Magee, aged 32, blended in. Clean-shaven, neatly dressed, he could have been a tourist or a travelling salesman. He said and did nothing that would stand out. Anyone paying close attention might have noticed a missing fingertip on his right hand, and perhaps they would have sensed a wariness, a coiled tension in his manner – but no one was watching him.

For more than a decade he had been on the radar of security forces. The Royal Ulster Constabulary in Northern Ireland, the British Army, Ireland’s An Garda Síochána, London’s Metropolitan Police, the British domestic intelligence agency MI5, the overseas intelligence agency MI6. Each had files on Patrick Joseph Magee, one of the best operatives in the Irish Republican Army.

He had grown up poor in Belfast, and the often gritty accommodations of life in the IRA – ditches, outhouses, jail cells – in no way prepared him for this kind of splendour. But he could not betray any unease, any hint of interloping into an alien world. To operate in England was a performative act. Magee was behind enemy lines, cut off from the movement’s network of sympathisers. He had to cloak himself in a different identity and conceal the West Belfast accent that so alarmed English ears.

Striding past the restaurant, passing under a sunlit atrium, Magee was visible to all. But what was there to see? Just another visitor approaching the reception desk. A young receptionist, Trudy Groves, smiled in welcome. Magee requested an upper-floor room with a sea view. Three nights. He was polite and soft-spoken, the accent English, with perhaps a hint of the Midlands. The hotel was enjoying a good September but had rooms available. Groves presented a registration card.

Magee would not have been human if he did not hesitate at this moment, a crucial test of fieldcraft he would have rehearsed. The trick was to fill in the card without his hands touching it, to leave no prints, and do so without looking awkward or drawing attention, leaving the receptionist with no memory of this encounter. He was to be forgettable, a blur. The pen hovered, then etched its fictions. Nationality: English. Address: 27 Braxfield Road, London, SE4. Magee printed and signed a name: Roy Walsh. The bill for three nights’ bed and half board (two meals included) was £180. Magee paid up front, in cash. Groves filed the registration card and handed over the key to room 629.

As Magee ascended to his room, his target was 90 miles north in the Buckinghamshire countryside. Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s first female prime minister, was in her fifth year of power. She had won two general elections and a war and was now busy wrenching the UK’s economy towards freewheeling capitalism. On this sunny Saturday, Thatcher was at her country residence catching up with friends while keeping tabs on a diplomatic crisis in South Africa, talks with China over Hong Kong, and a coal miners’ strike.

There was also the vexing matter of her speech at the upcoming Conservative Party conference. It would be the climax of her party’s annual get-together, a chance for cabinet ministers, members of parliament, and party activists to give a standing ovation and chant “Maggie!” They did so every year. But Thatcher agonised over the text. Behind her trademark armour-plated confidence, she fretted the speech would fall flat and disappoint her audience. She was already tormenting her speechwriters with notes and revisions. Everything had to go right at Brighton.

Once, Patrick Magee had dreamed of being an artist, but Ireland’s history swept away his canvas and conjured a new devotion. His job was to assemble and plant the device. Room 629 was his workshop. Slowly, painstakingly, he would lay out a tangle of wires, batteries, and timers, as well as a mound of gelignite, and step-by-step build a precision weapon.

He had three days and nights to complete and conceal the bomb. It was to hold its breath for 24 days, six hours, and 32 minutes. Then, if all went according to plan, from room 629 there would be a blaze of light, a sound like thunder, and the heart of the Grand Hotel would crack, unleashing vengeance on those below.

The explosives were commercial nitroglycerine-based gelignite. “To be certain of killing Thatcher, only the use of a high explosive such as plastic or dynamite could ensure success. I only had gelignite to work with, albeit a sizable amount,” Magee noted later. He and the IRA later claimed to have used 100 pounds of explosives. Investigators estimated it was about 25 pounds.

The other two crucial elements of the device were a PP9 nine-volt battery about six inches high and two inches wide, and a timing power unit. Police later surmised all the materials would have fitted into a briefcase or a small suitcase.

The device had at least two timers, two batteries, and two independent circuits, so if one circuit failed there was a backup. The explosives needed to be moulded into the required shape and wrapped in plastic wrap dozens of times – a slow, painstaking process – to mask the marzipan-like odour.

At approximately 9am on Tuesday September 18, Magee checked out, walked out on to King’s Road, and disappeared. In the dark cavity beneath the tub, the electronic timer pulsed in silence.

In the early hours of October 12 1984, the Tebbits were in room 228, behind the hotel sign that adorned the Grand’s facade. Norman Tebbit changed into his pyjamas, climbed into bed beside his wife, and was soon asleep.

In the rooms above them, other couples followed suit. In 328, two Jack Russells, Smudge and Lucky, yapped when Sir Anthony Berry and Lady Sarah Berry, 18 years married, glamorous in a tuxedo and a red dress, returned to their room. Sir Anthony was an aristocratic MP and junior government figure. He walked the dogs before climbing into bed around 2.30am. Normally Sarah slept to his right, but she had calls to make in the morning, so she slept on the other side, by the phone.

Approximately 30 feet above in room 428, John and Roberta Wakeham, 19 years married, were deeply asleep after a hectic few days. As the government’s chief whip, tasked with keeping MPs in line, John had to be everywhere, taking the pulse of the party, gathering intelligence for Thatcher. He was diligently supported by Roberta, a vivacious personality who disguised it all as fun.

In 528, Eric and Jennifer Taylor, 24 years married, got into bed around 2am. A week in Brighton had been Eric’s reward for serving as chairman of the North-West Conservative Association, a low-profile cog in the party machine. On Monday, he would return to his data-managing job and Jennifer would resume running a beauty salon.

In 628, Gordon and Jeanne Shattock, 32 years married, were in bed by midnight. Gordon had wanted to be an MP, but his veterinary practice left little time and money to run for office, so he settled for being chairman of the party’s western area. Jeanne was a magistrate and a school governess, and chaired a cancer charity. The conference was their big week off, an annual adventure. After noisy guests woke the Shattocks around 2.30am, the couple struggled to get back to sleep.

Beside them, in room 629, dozed Donald and Muriel Maclean, 27 years married. Donald was president of the Scottish Conservatives, a grand title for a soft-spoken optician who lived in a bungalow in the coastal town of Ayr. Muriel shared his interest in politics, but looked forward to returning to her embroidery and hill walks.

By 2.35am, the lounge bar had stopped serving, but the portrait of Queen Victoria still had dozens of lingering drinkers to scowl at. As the bomb in room 629 counted down its final minutes, the Grand Hotel’s roof enclosed 286 people. 220 residents, 32 visitors, 11 staff, and 23 police officers.

At 2.45am, Margaret Thatcher was wide awake, still in her ball gown, seated in an armchair in the Napoleon Suite lounge. The promenade outside was deserted save for a few police guards. The prime minister was pleased. She had just approved final amendments to her speech. The writers filed out, exhausted, and handed the text to the secretaries in the room across the hallway for typing.

Denis was in the suite’s bedroom, asleep. Robin Butler, Thatcher’s most senior civil servant, sat opposite her, eyelids drooping, looking forward to bed. He suggested leaving a few pending minor government matters till morning.

“I’d much rather do it now,” said the prime minister. Butler nodded. Of course she would. He waited while Thatcher rose and went to the bathroom. Seconds ticked by, the Napoleon Suite silent. Thatcher reappeared at 2.52am and sat in the armchair. Butler handed her a document about funding for the Liverpool Garden Festival. In the cavity beneath the bath in room 629, the timer pulsed into its final minute.

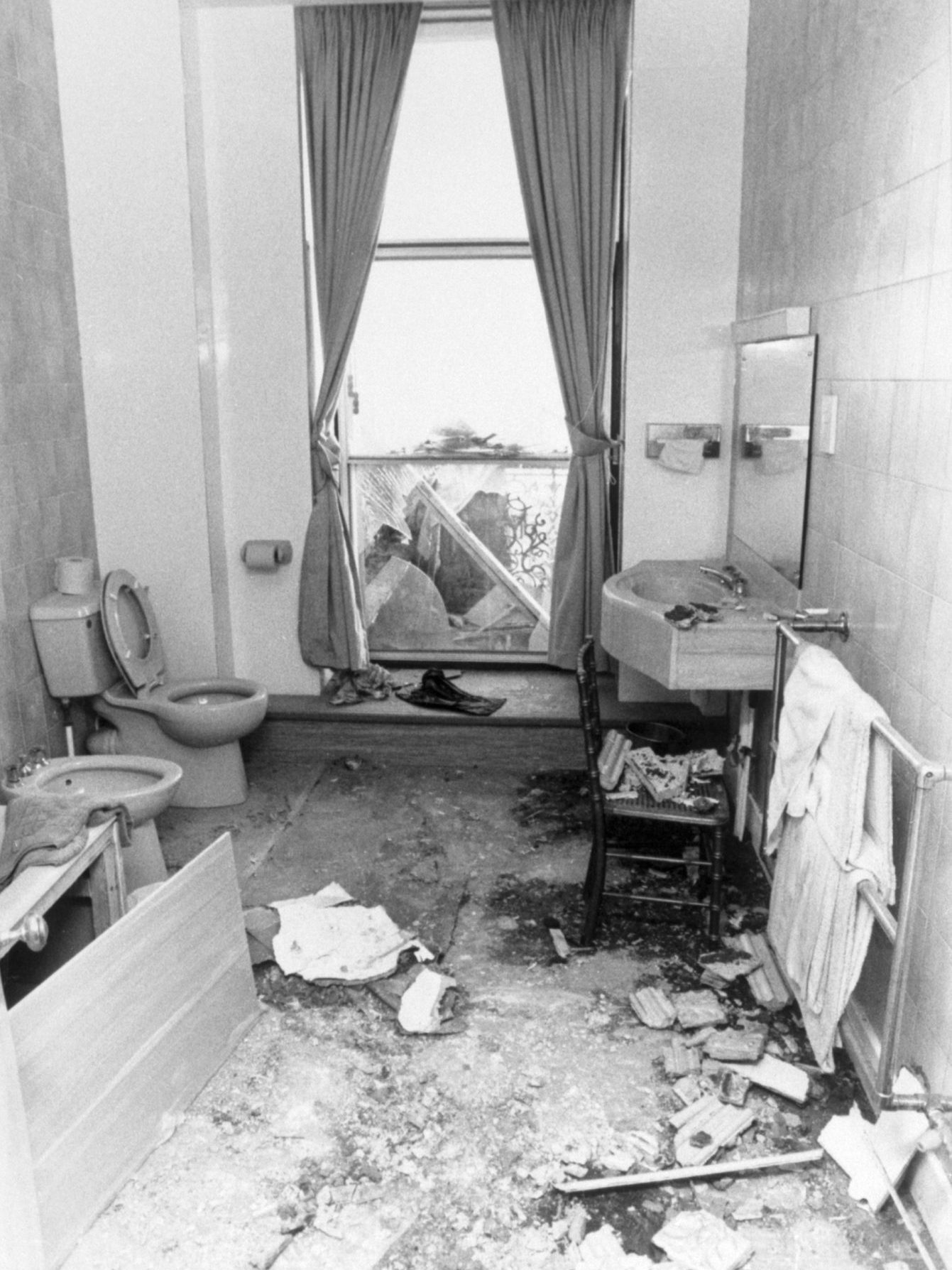

At 02.54:01, the bomb in the bathroom of room 629 detonated. A brilliant, blinding white light pierced the walls and corridors and brick facade. It exploded into the night air, dazzling and blurring the surveillance camera.

A fireball whooshed through the sixth floor, driven by the exponentially expanding force of the explosives’ compressed power. Blast waves radiated outward through brick and stone, unleashing a roar like thunder.

In 629, Donald and Muriel Maclean flew out of bed and spun through the air. Muriel, age 54, hurtled sideways. Her husband seemed to go upwards. The wall separating the bathrooms of 629 and 628 dissolved just as Jeanne Shattock, age 55, was in her bathroom bending over the bath. The bomb’s heat seared her flesh. Fragments of metal, ceramic, wood, and a green plastic lipstick holder stabbed her with the force of rifle bullets. The blast propelled her body across the corridor into a cupboard in room 638. She was decapitated. Gordon Shattock glimpsed the flash in the bathroom and felt a burning sensation before being hurled out of bed. The surge of heat appeared to pursue him through the air.

In the room above, 729, Harvey Thomas found himself flying through space. He thought he was dreaming about asteroids.

The blast wave continued upwards through the eighth floor and exploded through the roof, shooting tiles into a starlit sky. A flagpole snapped off and arced over the promenade on to the beach.

The eruption engulfed one of the two great chimney stacks with a velocity greater than a typhoon’s. For generations, these 11-foot-tall stacks, each with five stone funnels, had belched smoke from hundreds of fireplaces. Central heating had made them redundant, but still they soared with symmetrical precision over the centre of the Grand. Now the western stack, a five-ton exemplar of Victorian engineering, encountered the full force of late-20th-century terrorist technology. An unequal match. The stack fell.

With a rumble never forgotten by those who heard it, the masonry cracked and smashed through the roof, gathering speed and violence as it plunged downward, room by room, impelled not by explosives but that other unforgiving force, gravity.

Harvey Thomas realised he was not dreaming but flailing through a void filled with bashing objects. Gordon Shattock experienced a slow-motion descent into Hades. “There was no floor and I started to fall into a pit,” he recalled. Girders, concrete, and bricks crashed down with him. “I seemed to be falling faster than the debris and I had the feeling if I hit anything solid the debris would catch me up.”

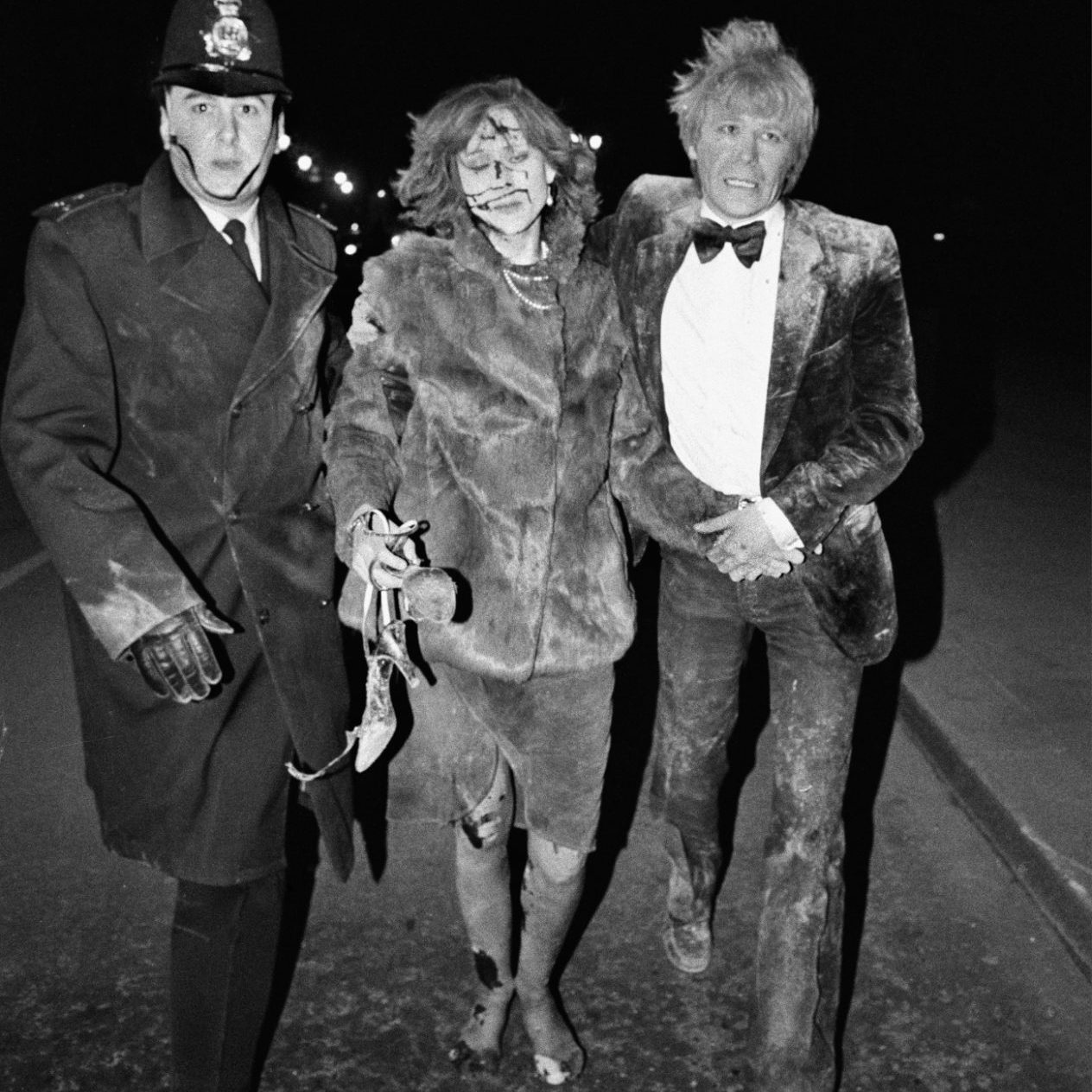

The avalanche punched through the ceiling of 528 and collected Eric and Jennifer Taylor and everything else in their room as it hurtled down into 428, where it swept up John and Roberta Wakeham. Then 328 was obliterated, casting Anthony and Sarah Berry and their dogs into the vortex.

In 228, Norman Tebbit, lying in bed, eyes wide open since the blast a few moments earlier, saw the chandelier sway above him. “It’s a bomb,” he shouted to his wife. Then came a deafening roar, and the maelstrom swallowed them.

When the bomb detonated, Margaret Thatcher heard a muffled crash and felt the room shake. Plaster dropped from the ceiling. A slab of glass from a shattered window splintered into shards on the green carpet. She knew immediately it was a bomb. There were a few seconds of silence, then a rumble of falling masonry. The prime minister stood up and went to the window, suspecting a car bomb on the promenade.

Robin Butler said: “I think you ought to come away from the window.” Thatcher ignored him. Then, oblivious to the homicidal cascade falling above, she darted for the bedroom. “I must see if Denis is all right.” She opened the door and vanished into darkness. Butler watched in horror. He could hear the Napoleon Suite’s bathroom collapsing. A thought honed by decades in government assailed the prime minister’s chief civil servant. “If she’s gone to her death, what am I going to tell the commission of inquiry?”

A moment later, to Butler’s immense relief, Thatcher reappeared with Denis, who was pulling clothes over his pyjamas and digesting the destruction to the bathroom. “I’ve never seen so much glass in my life.”

They went out to the corridor and saw a police bodyguard trying to kick open a door to a suite occupied by Geoffrey Howe, the foreign secretary, and his wife, Elspeth. The Thatchers and Butler scrambled into the secretaries’ office opposite the Napoleon Suite.

With the Grand Hotel still groaning and cracking, the prime minister sat in a chair and murmured to no one in particular, “I think that was an assassination attempt, don’t you?” Later, as the dead and the maimed were tallied and Thatcher made a defiant conference appearance, the IRA would release a statement declaring: “Today we were unlucky, but remember we have only to be lucky once, you will have to be lucky always.”

An extract from Killing Thatcher, The IRA, the Manhunt and the Long War on the Crown, by Rory Carroll, published by HarperCollins @ £25.00

Copyright ©️ Rory Carroll 2023