This week’s Supreme Court decision doesn’t just mean that another vote on Scottish independence is at least two years – and probably many more – away. Even further away still is the moment when a newly independent Scotland might return to the EU.

While many Scots were content with both the British and European unions, the UK’s regrettable departure from the latter, followed by a “make Brexit work” consensus between the big two parties at Westminster, seemingly obliges a choice of one over the other. For large numbers of pro-EU voters, independence now represents the most reliable means of Scotland regaining EU membership once again.

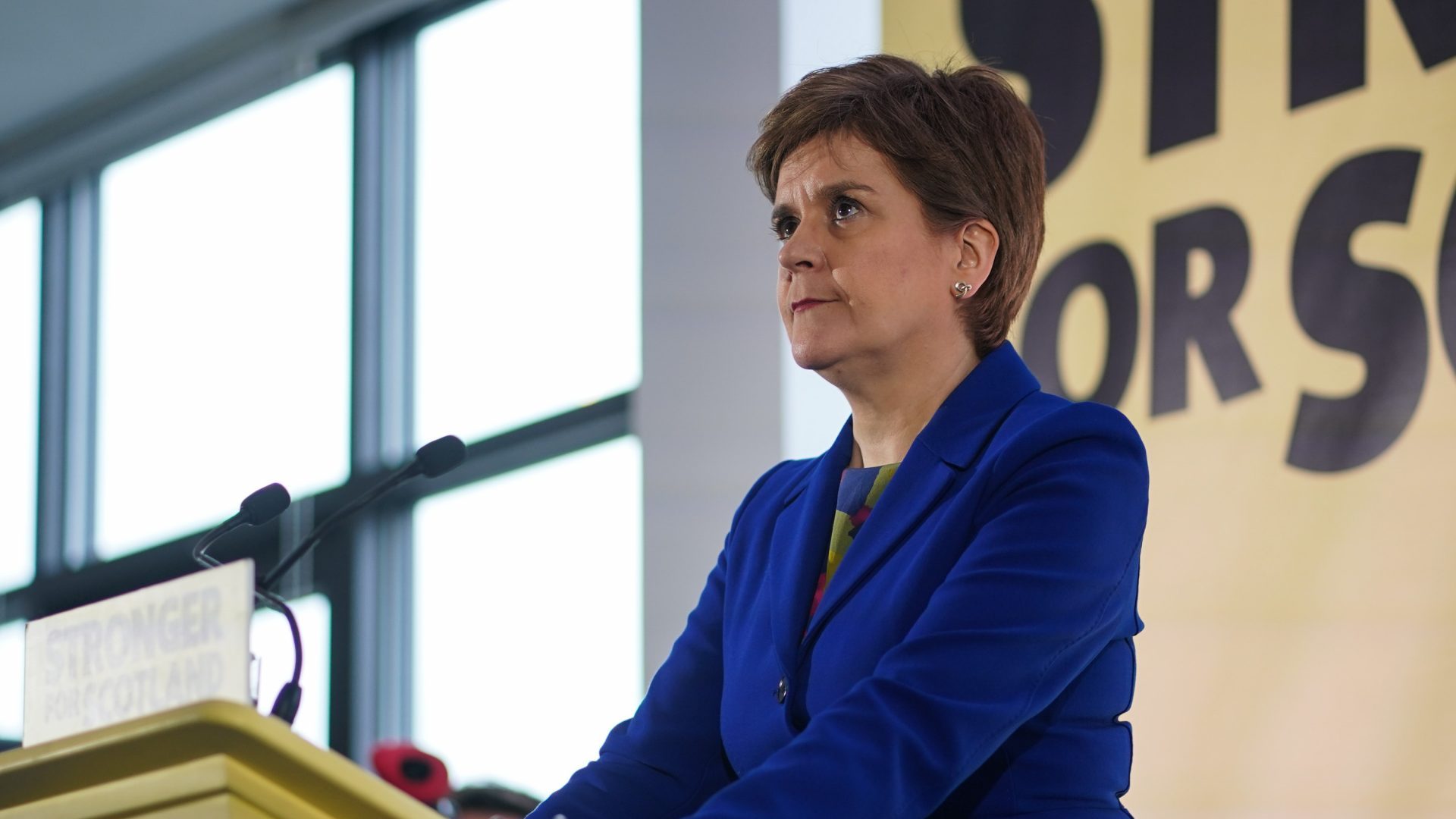

With IndyRef2 now off the table in the short-term but Brexit increasingly unpopular, across the UK, will Nicola Sturgeon turn up the dial on criticism of the decision to Leave and the way it has been handled? The SDP’s promise of future EU membership for Scotland is a core plank of its independence case and the party’s stance has been pro-EU for decades. Sturgeon’s government never misses a chance to remind anyone of its affinity for the bloc.

Nevertheless, the SNP leadership has substantially solidified that position since the UK left the EU. It has marginalised alternatives to the EU (mainly joining the European Economic Area via the European Free Trade Association) and shown independence supporters and the wider public that, as far as it is concerned, full membership is the only game in town. Per the SNP, the options are “Brexit Britain” or “European Scotland”.

That contrast is convenient, if oversimplified. The fact is that, despite the abundance of European sentiment in Scotland, the political conversation on potential Scottish EU membership (and Scotland’s EU relationship as part of the UK) is dismal. Most in the Scottish political system know little of how the EU functions, what is on the EU agenda (much less what to make of it) or how the EU accession process works. It is a strange state of affairs, given the aspiration of some for Scotland to be an independent EU member state. In any event, and even if the path to it may not be clear, the issue of prospective EU membership merits a serious debate.

As we know, Scotland’s path to EU membership would be predicated on a referendum result in favour of independence and a transition to statehood endorsed by the UK state. A viable route to independence and subsequent EU membership needs extensive bilateral cooperation between the two governments. In the absence of such cooperation, Scotland would have no reasonable prospect of joining the EU, since surely no EU member would recognise Scotland as an independent state if the UK did not do so either.

Assume, however, that the long-running dispute over a second referendum is somehow resolved and the Scottish electorate then votes for independence. Attention would then turn to sequencing. Scotland would only be able to apply to join the EU once it was an independent state, so the transition to statehood would first have to be completed. Yet Scotland would also need a foundation for its relationship with the EU, from the date of independence to the date of accession. In my work, I have suggested an EU-only association agreement (meaning concluded directly by the EU, rather than its member states) negotiated during the transition. That approach would require political will from EU members and the UK government.

After independence, Scotland would follow the normal EU accession process. That reality cuts both ways – the EU would neither create a special route just for Scotland, nor hold it in a non-existent queue. Like any other candidate, Scotland would need to garner support from all member states at each stage, since enlargement requires unanimity in the EU Council. It seems unlikely that any member would begrudge Scotland enough to put the brakes on its accession pathway, but it would be incumbent on the Scottish government to be proactive in understanding the positions of EU capitals.

An independent Scottish state would be favourably placed to meet the Copenhagen criteria (political, economic, institutional) set by the European Council for joining the EU. Scotland is an established democracy with a free market economy – and it was previously part of the EU for 46 years. The actual work required to make Scotland ready for membership would be on the institutional front. It would need to build the state institutions it presently lacks in its own right.

People often speak of Scotland “rejoining” the EU. That is a misnomer – not simply because Scotland has never been an EU member itself, but because it belies the transformation that would be involved to make Scotland first a state and then an EU member state.

Given Scotland’s existing qualifications to fulfil the Copenhagen criteria necessary for joining the EU, its journey to membership would be faster than other current, former and potential candidate countries. However, the various stages of the accession process, from the screening of Scotland’s laws and policies to determine their alignment with the EU’s acquis communautaire to the ratification of the accession treaty by the parliaments of the member states, take time regardless of the candidate’s starting position.

Moreover, while the level of enthusiasm of the EU institutions and members for a candidate matters, the duration of the process would in large part depend on Scotland itself. Where it prepared during the transition to independence, built its state with EU membership in mind and implemented changes requested by the EU, the path would be shorter; where it did not, the path would be longer.

In my research, I have calculated that Scotland could take 44-78 months to join the EU, from the date of application to the date of accession. Within that range, 48-60 months – four to five years – would be a reasonable estimate. Hypothetically, if a referendum took place on the Scottish government’s announced date, October 19 2023, that was agreed with the UK government and produced a majority for independence, the transition to statehood could reasonably take three years. Scotland might become an independent state on October 19 2026 and apply to join the EU on December 1 2026. Depending on whether the process took four or five years, Scotland could become an EU member state between January 1 2031 and January 1 2032. In that scenario, Scottish EU membership would be around a decade away from today.

Generally speaking, the purpose of EU accession negotiations is to achieve the candidate’s alignment with the acquis and convergence with the EU. At the same time, an independent Scotland would have distinct circumstances that would need to be addressed through negotiation, stemming from either its status as a new state or its relationship with the residual UK.

Economic policy would be one focal point – especially the EU’s fiscal rules for member states on national debt and deficit. While those rules may be revised in the post-pandemic context, Scotland would nevertheless probably seek transitional arrangements in this area, as the costs of establishing a new state would have a unique impact on the public finances.

Another point of attention would be currency. It is unclear exactly what currency Scotland would be using at the time of applying for EU membership or joining the EU. If it did not have its own currency, a solution would have to be found on the EU’s rules on monetary policy (since Scotland would not truly have one).

With the UK no longer a member, the collective EU appetite for new treaty-level opt-outs for individual member states has surely waned. In any case, Scotland would not have the heft to demand or secure major opt-outs (which would also diminish the claim that it was fully invested in the EU). However, it is likely that Scotland would be able to secure an opt-out or equivalent arrangement on the Schengen area, given that it would share an island with the non-Schengen UK.

Indeed, the conventional wisdom is that an independent Scotland would remain in a renewed Common Travel Area with Ireland and the UK, instead of joining Schengen. Among other issues, fisheries could be another focal point, as they are both an integral part of EU membership and a sensitive topic in Scottish politics.

If Scotland followed standard practice, it would hold an EU accession referendum after the negotiations had concluded. Provided that the electorate approved the terms of membership, and the EU completed its own ratification procedures, Scotland would become an EU member state on the date in the accession treaty.

At that point, its relationship with the residual UK would be shaped in large part by the EU-UK relationship. The inevitable border between Scotland and the UK, particularly in respect of trade, would be defined by the Trade and Cooperation Agreement or its successor arrangement. In terms of bureaucracy, trade between Scotland and England would be comparable to that between England and France.

As a country of 5.5 million people, Scotland would be a small EU member state. In order to be successful and influential for its size, it would have to embrace European integration and internalise EU affairs into its domestic politics in ways which the UK never did. It would have to overcome its current lack of Europeanisation. Inherently on the geographical periphery of Europe, Scotland would need to elect to be part of the political core of the EU, including by eventually adopting the euro voluntarily.

Joining the EU would shape countless aspects of a Scottish state. Like the rest of statehood in practice, Scotland would have to evolve significantly to succeed.

Anthony Salamone is managing director of European Merchants, a Scottish political analysis firm based in Edinburgh