I am not a reliable narrator. I know the subject of this story well. Matthew Brown and I both attended the same provincial Comprehensive, leaving with less than impressive results, an irony that was lost on our respective fathers — both of them were teachers. Later, the two of us would go on to underwhelm an uninterested public with a series of ramshackle punk bands, before clawing our way back into the educational mainstream.

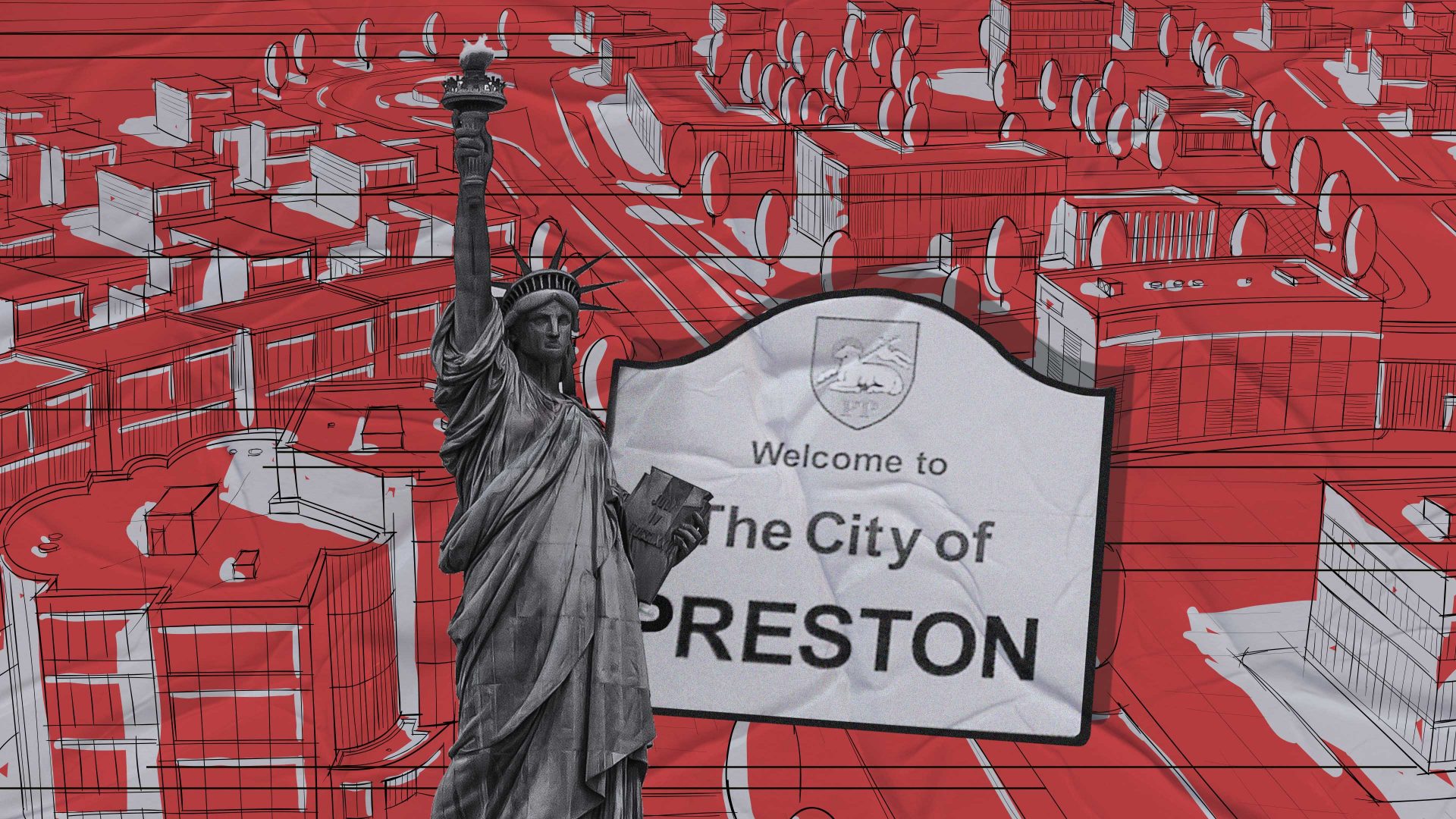

I went on to work as a foreign reporter. Matt did something more significant. He helped turn around the fortunes of our hometown, Preston, and improve the lives of countless people.

I remember returning to Preston from overseas after the financial crash. Much of the high street had been boarded up, plywood windows testament to the jobs and lives of the people who had once worked there. A £700m redevelopment scheme had collapsed, after its principal tennant, John Lewis, had pulled out in 2011. The Tithebarn Project, slated to be built by two of the world’s largest development companies, was canned. Businesses across the city closed and unemployment for many became the norm.

This is really where Matt comes in. He got a place on the Labour council and a few years later went on to be named leader, a position that he used to show that local government really can make a difference. In 2018, PwC, the professional services firm, awarded Preston Most Improved status, taking into account a range of measures including employment, the environment and levels of social equality. On those criteria, the city had become a better place to live than the capital. Much work remains to be done – Matt will be the first to tell you that. But what Preston has achieved is remarkable.

At its heart, the Preston Model of community wealth building (CWB) is a fairly straightforward proposition. It relies on employees having a direct stake in the businesses and institutions that pay their salaries. Under CWB, multinational corporations relying on economies of scale to compete against local minnows on price are replaced with a network of local companies and emerging cooperatives.

Set down here, it hardly seems radical. However, these ideas are being noticed across the UK and Europe.

“It’s not extractive,” Matt explained. “Whatever it pays, it keeps in the community,” he says of Preston’s own spending. “However, we’re not done yet. It takes time. We need to extend the model, to build in additional layers and make it more durable.”

Odd as it seems, the capacity of local government to make major changes has become almost entirely overlooked. It doesn’t need to be that way. According to a study by the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) 58% more of the money spent by authorities with small local companies remains within the local economy, compared to that spent with large companies in the same region. Consider the immense value of local government spending nationally, or even across Europe, and you have some idea of the economic and social potential at local governments’ fingertips.

In retrospect, neither of us received much of a political education at school, where stressed teachers smelling of instant coffee and stale cigarettes hammered out the rudiments of maths and geography in chalkdust, spittle and decibels. If anything, our journey towards what you could crudely call some kind of political awakening came from the generation before, learnt at the knee of Joe Strummer and The Clash, establishing within our porous teenage minds the founding principles of lives worth living.

It’s a view that still shapes many of us. Matt and Preston Council would hardly claim to have invented the model. Its roots within communities stretch back to the explosion of cooperative movements in the 19th Century and, principally, to the town of Mondragon in the Basque region of Spain. Trapped without a future and left to endure the worst privations of the economic and social destruction that followed the Spanish Civil war, Mondragon was a town without direction or future. But then, in 1956, a young Catholic priest founded a technical college to develop the skills of the population and to help shape and manage the workforce. Eventually, locals established a cooperative Corporation. It is now the biggest business group in the Basque country.

In a story of second chances, you can see why that of Mondragon may have resonated with Matt. After languishing in the doldrums of the DHSS and dead-end temporary work, both Matt and I, though avowed non-believers, were able to gain access to an Oxford college, operated by the Catholic church and affiliated with the University. It’s hard to stress how pivotal that change was, thrusting us from the dole queues of the north into a landscape that owed more to the erotic pre-war fever dreams of Evelyn Waugh than anything we had experienced or imagined. Armed and educated, Matt returned to the local university and the town where he had celebrated his coming of age in a local curry house, if memory serves.

Mondragon’s success provided a clear example to the councillors of Preston, who visited the cooperative in the middle of the last decade. From there, they combined the ideas for the potential of cooperatives, with economic theories emerging from the US rust belt. Building upon a purchasing model developed in Manchester, Preston established itself, not simply as the means to reroute expenditure back into the economy, but as a direct means of transferring the town’s wealth away from distant shareholders towards the people that made up a community.

Phil Thompson, the former Deputy Mayor of New York told The New European, “Community Wealth Building is a new term but not a new concept. What drew me to it is that it resonates with the more communal and integrated approach to economic development. I was exposed to it at a young age during the Civil Rights Movement,” he said. “Preston was helpful as a proof of concept and some practical approaches that spurred our thinking in New York. Everything we did, however, and I think this is true everywhere, had to be grounded in our own political realities.”

The liberal press, left wing columnists and activists, such as the actor Michael Sheen, have all beaten their way to Preston’s door, eager to see what a progressive response to regional disparity might look like. However, in Westminster, its fortunes have been mixed. Initially picked up by Jeremy Corbyn as an example of a Labour Council enacting real change, his successor, Keir Starmer, has proven a less than enthusiastic cheerleader. The current leader has put as much political water between himself and his predecessor as possible.

Nevertheless, across Europe, the Preston Model continues to gain ground. Dublin, Barcelona and Copenhagen are all drawing from the town’s example while, within the UK, regional councils, including London and North Ayrshire are looking at ways of putting local authorities at the centre of the areas they serve. The Welsh Senedd has proven especially enthusiastic at the prospect of putting the power of a devolved government at the service of the community.

“Preston has demonstrated the ability of local government to do things that had only previously existed in theory,” Sarah Longlands, the Chief Executive of The Centre for Local Economic Strategies said. “It gave people confidence in the potential of local government across Europe. I know that right now Matt and others are getting calls from authorities across the UK and Europe asking how they can do what Preston has done.” The benefits of Community Wealth Building don’t need to belong to the left, or the right, Sarah said, “It’s just a propgressive response to local economic development. Local authorities shouldn’t be just about counting the pennies. They can do so much more than that,’ she said.

I currently live in North Africa, a continent away from the streets and people Matt and I grew up with. I messaged him just last night. It had nothing to do with this. I’d discovered some David Bowie trivia I wanted to share. However, conversations ebb and flow and, eventually, it turned to the Preston Model and the work still to do. He told me about his plans for a new publicly owned cinema and a community operated bank that would serve the entire Northwest. He sounded tired. Central government continues to reduce the powers of local authorities. A recent report by the Resolution Foundation cast a dismal pall over growing regional disparities, with the gulf between London and the North wider than ever. In Preston, the cost of living crisis is eating away at his community. There’s a lot of work ahead of him, but he’s still there and he’s still doing it.

Matthew Brown from school, making the world a better place.