Poisoned, then shot; shot; shot; poisoned, then killed. Those are the outcomes for Vladimir Putin’s opponents, in order: Anna Politkovskaya, Natalya Estemirova, Boris Nemtsov and now Alexei Navalny. I interviewed them all; they were all critical of Russia’s tsar; they are all now dead.

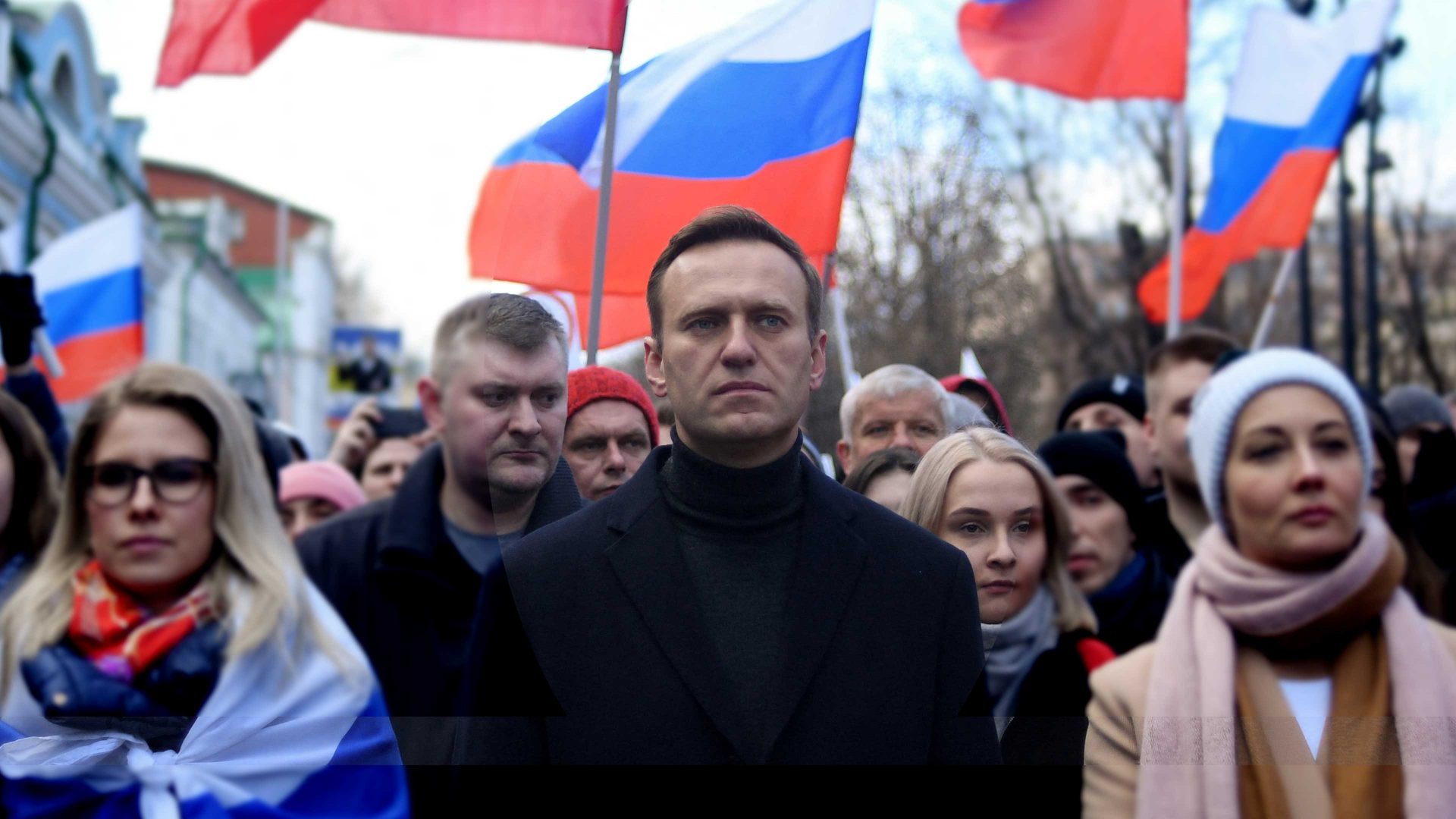

Alexei was a difficult man, but that comes with the territory when you have to stand up to Putin. He was also charismatic, very; tall and blue-eyed, a natural leader whose sardonic love of the absurd saved him from turning the corner into some kind of messiah. He started out as an anti-corruption lawyer, rode along with the far right in 2007, left that miserable episode and joined the opposition mainstream – when Putin returned to the Kremlin in 2012, Navalny ran against him.

I first interviewed him via Zoom when I was in Southend-on-Sea. When the tide is out, the Essex Riviera does a bloody good impression of a bleak Siberian wasteland. I held chips in the air, waiting for Essex seagulls to pounce on them, the gag being that we were focussing on an investigation Navalny had made about Russia’s then fabulously corrupt prosecutor-general, Yuri Chaika – and “chaika” means seagull.

Navalny was scathing about Londongrad as a sluice for Russian dirty money, and he blasted Putin as “the tsar of corruption”. His words tolled as clear as a bell, and you knew that every syllable was a potential death sentence. It isn’t a surprise that the Kremlin had him killed in February 2024; the surprise is that he lived for so long. But even as I type this, I mourn him and cannot quite believe that this great force of nature has been silenced for good.

We first met in the flesh in Strasbourg in 2018. He had been suing the Russian government for blocking his candidacy.

In Moscow, Team Navalny had a seriously tough time, and while we were making our 2018 BBC Panorama, Taking On Putin, we caught some of that ourselves. We were followed everywhere, the cameraman and I were detained in a police station for desecrating a shrine to Boris Nemstov – a nonsensical charge – and our passports were published on Russian Telegram. But what happened to us was nothing compared with the treatment the Russian dark state handed out to Navalny’s people. One supporter was tasered, then stabbed and left to die in the snow; his office manager was beaten on the head with an iron bar, then charged by the police for stage-managing the assault on himself.

Another office worker was beaten black and blue by silent thugs, for live-streaming a police attack on Navalny election supporters. I had seen the work of the Russian killing machine in Chechnya undercover in 2000, and again in 2014 at the crash site of MH17 in Donetsk. I mourned the murders of my friends, Anna, Natalya and Boris, but I didn’t quite understand the ferocity of Russian fascism until we worked with Team Navalny. It’s for this reason that I find those people who side with Putin, like Donald Trump and Tucker Carlson, so beneath contempt. But Navalny never lost the laughter in his eyes.

Putin loves poison. When Navalny was poisoned with novichok, he fell into a coma. Angela Merkel managed to get him out to Germany. When he had recovered, he phoned up one of his FSB poisoners, pretended to be a Kremlin boss, and got him to confess – on tape – how they had done it. They had put the novichok on the seam of Navalny’s underpants.

Navalny was, of course, crazy to go back to Russia, but he understood that if he stayed in exile then his dream of another Russia would wither, then die. In his pomp, in 2012, hundreds of thousands of Russians hit the streets following his call to bring down Putin. Twelve years later, we see a few hundred Russians daring to lay flowers in the snow. And then, at night, watched over by police, men in hooded tracksuits remove the tributes, so that in the morning there will be no trace whatsoever.

John Sweeney’s Killer In The Kremlin is published by Penguin Books