In the early 1950s, during the dark days of the cold war, the Soviet propaganda machine began drawing attention to an inconvenient truth: for all its chest-beating about freedom and democracy, the USA was less enthusiastic about those principles if you happened to be black.

Worried about the effect of this obvious contradiction on its image in the non-aligned countries of the world, the US State Department decided to hit back, and unexpectedly chose the medium of jazz. After all, jazz was one of the few areas of American life in which blacks and whites mixed with some degree of equality. Not only that, it was an art form – the only art form – actually invented in America.

Accordingly, in March 1956 it sent trumpet star (and future presidential candidate) Dizzy Gillespie on a 10-week tour to the Middle East, Pakistan, Syria, Turkey and Greece. In the propaganda war, Dizzy explained, holding up his trumpet, “the weapon that we will use is the cool one”.

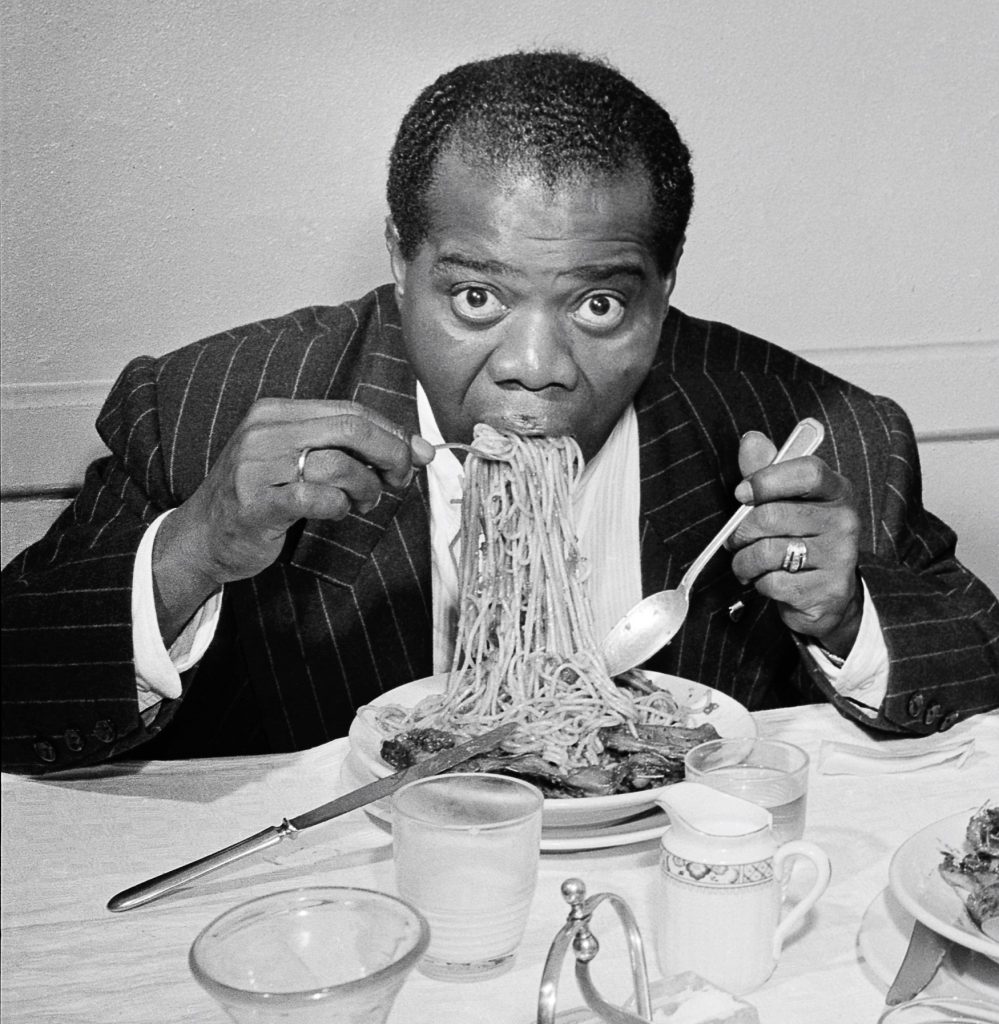

He was fully aware of the hypocrisy of the exercise. When the State Department invited him to a pre-tour briefing, he replied: “I’ve had 300 years of briefing. I know what they’ve done to us… I sort of liked the idea of representing America, but I wasn’t going over there to apologise for the racist policies of America.” Despite his ambivalence, the tour was a great success and was followed by others featuring Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman and Dave Brubeck.

But it’s a curious fact that while jazz’s star began to fade in its country of origin, it was a different story in Europe. Although Brubeck’s visit was the first foray by an American jazz musician behind the iron curtain, his compatriots had been visiting Europe since the earliest days of jazz. And while a mixture of racism and lack of work at home drove many of them eastwards across the Atlantic, in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, London, and above all in Paris, they were welcomed with open arms. Many of them decided to stay.

The exodus peaked between the 1950s and 70s, and it continues to this day, albeit on a more modest scale, and for a variety of reasons.

One early expat was clarinettist Mezz Mezzrow, who was Jewish and married to a black woman. He settled in France in 1948 and lived there until his death in 1972. “Most of the negroes who are here aren’t here because of the race question,” he explained, “it’s just that you can live your life the way you wish and nobody bothers you… people treat you as an artist, not the way they treat jazz musicians in the States.”

A year after Mezzrow’s arrival, the 22-year-old Miles Davis travelled to Paris to play at the first postwar Paris international jazz festival. He was already winning the admiration and respect of his fellow musicians in the USA, but outside the world of jazz, he had to deal with segregation and constant discrimination, and the existence in most states of laws outlawing sexual relationships between blacks and whites. France was different. “This was my first trip out of the country,” Davis wrote in his autobiography. “It changed the way I looked at things for ever… I loved being in Paris and loved the way I was treated. Paris was where I understood that all white people were not the same; that some weren’t prejudiced.”

His lifelong love affair with the white singer Juliette Gréco began then and there. The impossibility of their relationship surviving in America was made rudely apparent a few years later, in New York, when Gréco invited Davis to the Waldorf Astoria for dinner. There, she was no celebrated French chanteuse, merely a white woman shamelessly consorting with a black man. After they had waited almost two hours for their food to be served, the waiter finally slammed their plates down on the table. Gréco never forgot the humiliation. “In America, his colour was made blatantly obvious to me, whereas in Paris, I didn’t even notice he was black.”

The difference was rooted in France’s openness to the African cultures it had discovered during colonial rule, particularly in Dahomey and Benin. For many French artists, African masks and statues became a source of new ideas, which Pablo Picasso began exploring during the first decade of the 20th century. When young Africans came to France to study, and found common intellectual ground with the likes of Langston Hughes and other founders of the Harlem Renaissance, the Négritude movement was the result. Black culture was popularised by the sensational American dancer Josephine Baker, who sailed from New York to Paris in 1925.

By the mid-1950s the American jazz scene was changing. With the untimely death of Charlie Parker, the glory days of wild bebop were over, but the drugs lingered on, to the point where promoters sometimes paid the musicians in narcotics.

Saxophonist Stan Getz decamped to Copenhagen to escape his heroin addiction, living there for three years, marrying a Swedish woman and fathering two children with her. Two other giants of the jazz saxophone – Dexter Gordon and Ben Webster – followed suit a few years later. Their story is told in the award-winning Danish documentary Cool Cats, released in 2015 with the poignant tag-line: “They left their country – and found a home”. Despite the unfortunate detritus of their American lives, blighted by drugs, drink and endemic racism, what makes the film so profoundly affecting is that neither musician could quite believe how well the Danes treated them: paying them fairly, and promptly; allowing them the freedom to date white women; treating them as friends. It was no wonder they stayed so long.

Gordon eventually married a Danish woman and lived with her in the Copenhagen suburb of Valby, where he became a local celebrity. The affection the Danes held him in is illustrated by an episode in 1966, when he was arrested in Paris for drug possession and ended up serving jail time. At the end of his sentence, the Danish authorities refused to allow him back in the country. In response, his Danish fans held a large rally in Copenhagen demanding the reversal of the decision – and won. “They took good care of him,” commented fellow jazz exile Johnny Griffin. “That’s the way these people are.”

After enjoying mainstream success in the 1950s, jazz was on the wane in America. During the 1960s, the twin threats of the Vietnam draft and Beatlemania sent many more American jazz musicians into European exile.

Two singers who made the trip to London during the decade were Mark Murphy and Jon Hendricks. For Murphy, it was about quality of life. “London, to my way of thinking,” he said, “is a much nicer place to live than New York, because New York is a business city. It’s exciting, it’s fast, and everything is open late, but when it comes right down to living, there’s no comparison.” Jon Hendricks had been living in San Francisco with his wife and five children. Worried about the prevalence of drugs in Californian high schools, as well as the riots that were breaking out in cities across America, he put in a call to Ronnie Scott and got himself a month-long residency at the club, then uprooted the family and moved them to London. They stayed for five years. “The thing that makes me happiest,” said Hendricks, looking back, “is that it gave me the opportunity to bring my children into a fairly stable society.”

Even today, Europe attracts a steady trickle of prominent American jazz musicians: saxophonist Archie Shepp, pianist Kirk Lightsey, and the vocalists Michele Hendricks and Melody Gardot all live in Paris; drummer Greg Hutchinson is based in Rome; bass player Joe Sanders and his family live near Marseille; saxophonist Bill McHenry and bassist Michael League have both taken up residence in or near Barcelona, joined recently by drummer Antonio Sánchez.

Just as the Covid pandemic was taking hold, saxophonist Ben Wendel and his Czech-born wife moved from New York to Paris for eight months, and then to Amsterdam. It was a tumultuous time: in the 18 months they lived there, house prices rose by 35% due to the flood of money leaving London because of Brexit. “Living in Amsterdam was like Adult Disneyland or something, it’s so clean, it’s so safe, it’s so reasonable… I didn’t even know how much anxiety I had until I realised it was just a different pace. Spain has that feeling too. There’s more of a focus on, yes, we’re proud of our work, but let’s take a weekend where we’re not working. It’s a different sensibility.”

In America, he believes, it’s too easy to lose yourself in your work, for work to become your whole identity, although for him there are both positives and negatives: European business life, he feels, lacks the American can-do attitude.

But European healthcare came as a revelation. “If you’re an American and you’ve never lived in Europe, there’s no way to understand that until, as in my case, your appendix bursts while you’re playing a Brecker Brothers retrospective with Randy Brecker, and you have to go to an emergency room… Now, if you had that same situation in America, in New York, you might not go! You might say to yourself, shit, I don’t know, maybe I’ll wait another day. It’s probably food poisoning…”

It was in London that Washington DC native Rod Youngs, former drummer for Gil Scott-Heron, met the Englishwoman who is now his wife. After conducting a long-distance relationship for the best part of a decade, he finally moved over permanently in 1997 and got married. Professionally, he found there was a lot more opportunity and fewer obstacles. “You want to be in a place like London, which is an incredible hub for the arts, lots of great musicians here, and lots of world-class musicians come here to perform. You want to be with like-minded people.”

Would he go back to the US? “Absolutely not.” Not even for work? “No, not really. Particularly for the last five years, politically, I just don’t want to be over in that environment. It’s not the same place. It’s racism, but a lot of it is classism. You have this really wide divide between rich and poor, and a diminishing middle class. And you have this division, this infighting for what’s left of the pie. It’s just madness.”

But London is a less popular destination than it used to be. “Brexit has been a total disaster,” says saxophonist Jean Toussaint, who has lived there since 1987. “As a musician, it’s been terrible, as I’m sure you’ll hear from any musician you speak to. It’s made it a thousand times harder to travel to Europe, to tour, to work. Fortunately for me, I’m a dual American-

British citizen, so I have two passports I can use. But it’s a nightmare.

“Then there’s a tax situation when you’re working in Europe as well. They want to withhold tax on your pay. And then you’ve got to claim it back in the UK. It’s just a whole lot more red tape, and it’s made it a whole lot more difficult, and a lot of people have stopped touring to Europe for that reason. And European musicians are finding it more difficult to come here.”

To some extent, Britain’s self-imposed isolation mirrors that of America. “Americans don’t travel that much, so they don’t know anything,” adds Toussaint. “They’re being told, ‘you live in the best country in the world, so why do you want to go anywhere else?’ And then they go somewhere and they say, ‘Oh well this is better than what we got…’ The media and the government is constantly telling them how great they have it, and how [America] is the best place on the planet. And it is, for some. But for the majority it isn’t.”

The American Dream? “That’s right – pull yourself up by your bootstraps. But what happens if you don’t have any boots?”