Albert Einstein once said that the greatest power in the universe was “compound interest”. A strange quote from someone who helped to explain the powers that shape the universe – but he’s probably got a point.

The inevitable progress of growth on top of growth is a wonder to behold – and it helps explain why the UK is in a bit of a tizz about Poland. Because current compound growth rates indicate that Poland will be wealthier than the UK by 2030.

Average growth in Poland is 3.6%. In the UK over the last decade or so it has been 0.5%. If those trends continue, the average Pole will inevitably become wealthier than the average Brit. The same is true of several other eastern European countries. Both Hungary and Romania are expected to surpass the UK by 2040. Why are they growing at such different rates? And will it last?

It was not just post-war communism that held Poland back. Eastern Europe has been an economic underperformer for centuries. It has been fought over, split up, invaded, riven with social hierarchy, poorly educated and often treated with colonial disdain. Communism was just another burden.

Even after the fall of the wall, Poland was seen as a special case, worse than the rest and likely to remain the poor relative. But up until 2019 the Polish economy had been growing for 28 years, a record period of unbroken growth in the EU, and globally only surpassed by Australia. Poland’s GDP has increased seven-fold since 1990. It sailed through the credit crunch and kept growing. Even its Covid recession was shallow.

When an economy is held back for decades there is plenty of room for a surge. But Poland also had a young, dynamic and well-educated workforce. It avoided many of Russia’s mistakes, avoiding the mass corruption and oligarchy. It also did everything it could to get into the EU at the earliest opportunity, in 2004.

With that came development funds, better infrastructure, access to the huge European market and foreign investment. Almost 20 years ago I visited the region of Poland bordering Germany, and already it was a site of huge investment. New factories were being put up in massive numbers, for German, French and Dutch companies. They got cheap land, cheap highly skilled workers, EU funding and easy access to their own markets.

Poland seized the chance to make up for centuries of economic stagnation. It knew that it never wanted to be under the threat of Russian interference again and so it has fought not only politically and diplomatically, but also economically, to be as European as possible.

For the first 20 years of that Polish miracle, the UK was also doing well. It enjoyed a long period of growth. Trouble arrived in the form of the 2008 financial crisis, from which it has never really recovered. The near collapse of the banking system and financial services on which the UK economy is dependent, seems to have permanently weakened the country’s ability to sustain high rates of growth. The lack of growth and resilience meant it suffered more from Covid than other countries, and the UK economy has not even recovered to its pre-Covid size.

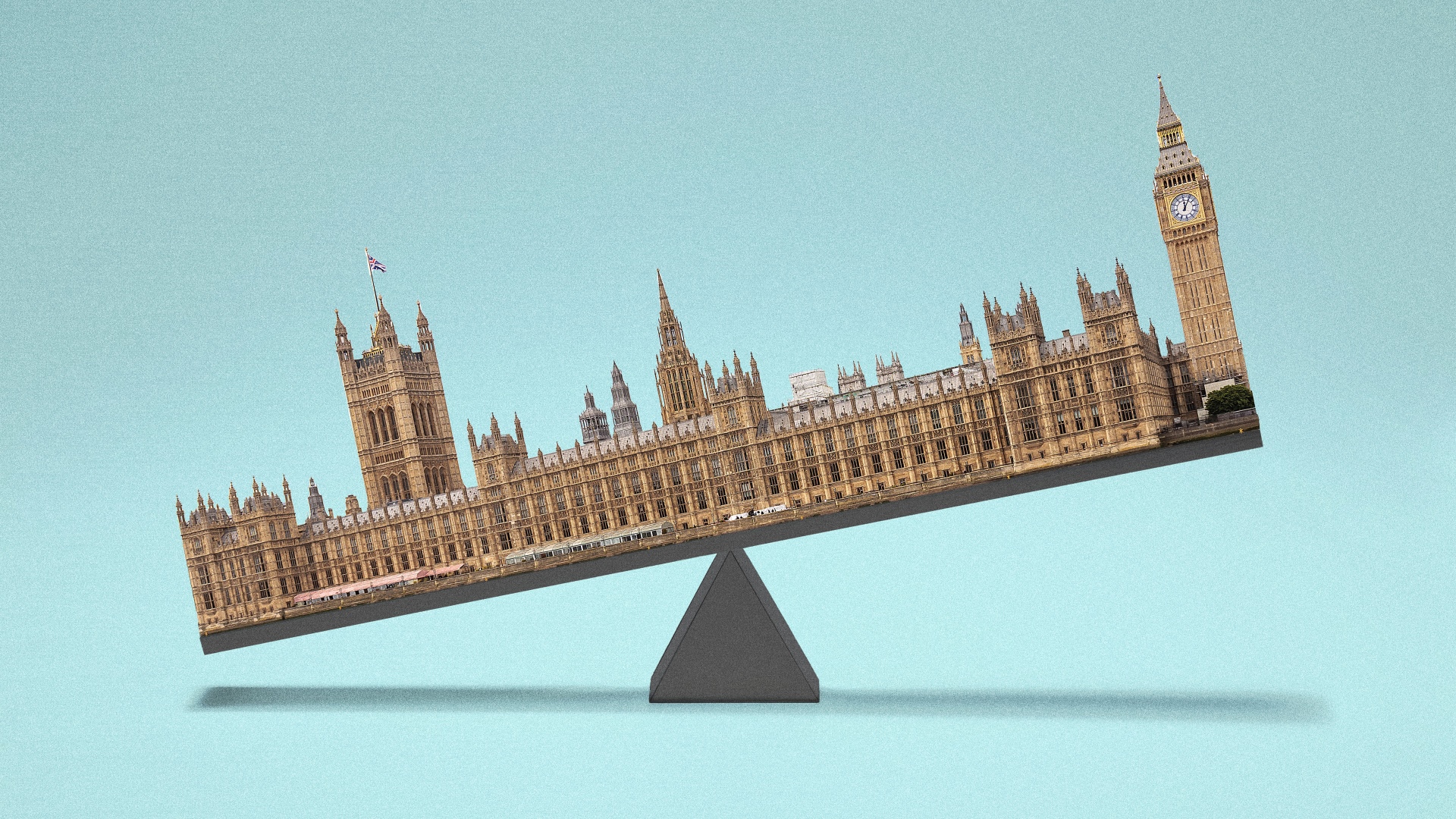

Instead it has been bouncing along the bottom for almost 15 years now. Productivity last grew this slowly during the 18th century, wages have failed to keep up with inflation, swathes of government are no longer up to the task, business investment has plateaued and shows few signs of recovering, and then on top of that we had Brexit. Brexit will cost at least 4% of the UK’s future growth, or to put it another way, it brings the date when Poland will overtake the UK at least one year closer. In fact, several parts of the UK are already poorer than Poland.

As they say in adverts for financial products, “past performance is no guarantee of future returns” – the Polish economy may not be able to maintain its breakneck growth rate. Its right-wing government is increasingly at odds with Brussels, and it can no longer rely on EU funds.

The war in Ukraine is a strain, as is the downturn in much of the rest of Europe, but the World Bank, which expects growth of 0.7% this year for Poland, is also expecting it to bounce back to 2.6% next year.

If Britain is to keep up with the Polish juggernaut, it needs to reform and go for growth. But that would involve all those things that this government seems incapable of, or unwilling to provide, such as skills training programmes, easier planning regulations, more spending on infrastructure, and above all a new technology strategy. But even if it had all those things, it would still be outside the EU, which is the deal breaker.

Just try to see it from the perspective of a foreign firm looking for somewhere in Europe to invest. You can place your factory on an island off the coast of Europe, with red tape and barriers to trade at every border, with poor infrastructure, low skills, and no industrial policy. Or you can go to Poland.

In part, the UK’s chagrin at the success of Poland and the imminent prospect of its overtaking the UK is down to a patronising attitude towards our formerly poor neighbours. Aren’t these the people who flooded into the UK after the creation of free movement in order to do the low-paid jobs we didn’t want to do? Aren’t they the fruit pickers and cleaning ladies? Isn’t eastern Europe a byword for backward, inefficient, economically weak regions? Well yes, they used to be, but not for much longer.

We should be delighted that eastern Europe is booming. We all benefit from a wealthier Europe, not least because it creates wealthy markets for our exports. Those cheap labourers and cleaners are going back with money in their pockets to a rapidly expanding and prosperous society at the heart of the EU. Getting upset because your cleaner is wealthier than you are is not a very noble sentiment. You might instead want to think about how they have done so well, and we have done so badly in comparison.

Oh, and if things get really bad, there will soon be plenty of cleaning and fruit-picking jobs available.

In Poland.