The effective exercise of power is based on ideas and the policies that arise from them. Successful implementation of a programme is dependent on ambitious figures uniting around a mission, willing to compromise in order to keep the show on the road.

When the ambitious sniff looming defeat, they are no longer bound to a leader or a common sense of purpose. Some prepare for future battles. Others wonder about a life outside politics. The perception of being ruled by pathetic fin de siècle governments feeds on itself. When exhausted rulers are seen as doomed, the ending becomes even more inevitable.

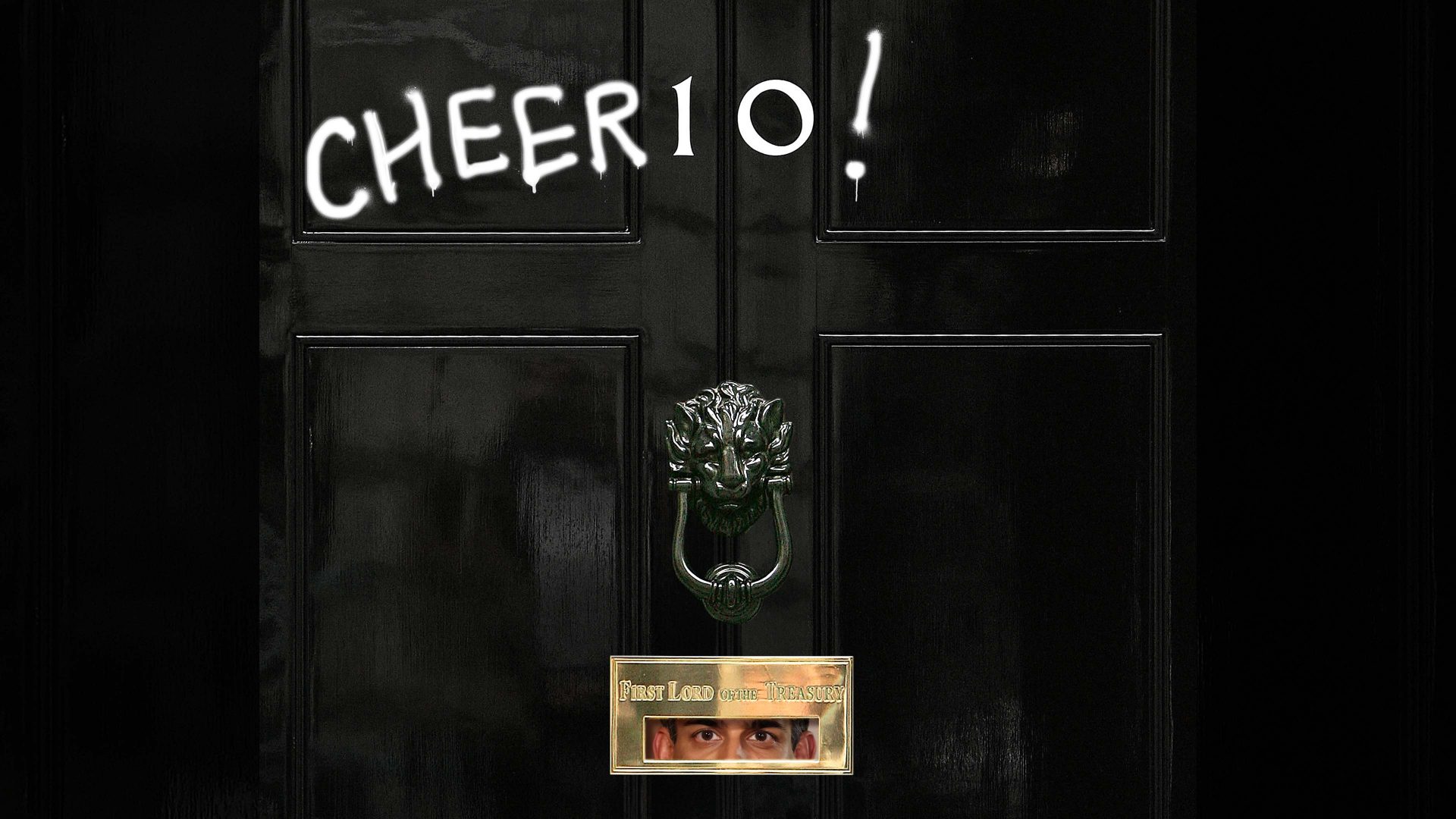

Few would dispute that we are living now through the dying agonies of a long-serving government. Those who once wielded power with an omnipotent swagger are long gone.

Boris Johnson is not even an MP. His former deputy, Dominic Raab, now near silent on the backbenches, is standing down at the general election. So is Theresa May, another of the prime ministers in this mad sequence of multiple leaders, fleetingly dominant before descending into Brexit hell.

Dominic Cummings screams from the sidelines when not so long ago he was powerful enough to remove the chancellor, Sajid Javid, another former senior minister who is leaving the Commons at the election.

The number of Tory MPs taking a traumatised bow will break all records by then. There are plenty more who will be announcing their departure in the coming weeks.

But the current fin de siècle mood goes much deeper. Consider the decadent images of recent months, a Conservative Party conference in which Priti Patel was seen dancing joyfully with Nigel Farage, Liz Truss speaking with Steve Bannon at a conference of the right in the US – an event that made Donald Trump seem like a cautious pragmatist, and the former Tory vice chairman, Lee Anderson, defecting to the Reform Party weeks after recording a video with Rishi Sunak together hailing their joint patriotic devotion to the UK.

Tory grandees in the House of Lords delayed Sunak’s plans to fly asylum seekers to Rwanda, an idea he considered to be too expensive when he was chancellor and one his current home secretary described as “batshit”. The bill was finally forced through parliament, but there is little time to celebrate with a local election nightmare looming, together with more talk of a challenge to Sunak.

Some rebels just want him out and Penny Mordaunt in, others want to impose on him an “election war cabinet” of senior right wingers including Patel, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Robert Jenrick as the price of not forcing a leadership election.

In order to get a sense of how this decadent collapse compares with previous governments in their death throes, we need to look back with forensic objectivity. It is easy to forget how fragile some of Sunak’s predecessors and their parties were as we are living through the end of a long volcanic period of one-party rule.

In 1979 Labour lost power, and did not return for 18 years. The end was humiliating. James Callaghan lost a Commons vote of confidence and had to call an election. He had even lost that unique prime ministerial privilege of choosing the date that best suited the governing party.

The election followed years of industrial turmoil, raging inflation and intense cabinet divisions on all the key policy areas from public spending levels to state ownership, Europe and defence. The battles were contested by articulate political titans and not the pygmies fighting it out at the moment.

All the titans had support in the Labour Party. One of them, Tony Benn, occasionally voted against government policy on the party’s national executive, even though he was a member of the cabinet. By 1979 the sense of an ending was pervasive even to Callaghan, who detected a “sea change” towards Margaret Thatcher that was unstoppable.

In some respects, the fall of Thatcher in 1990 was much more dramatic. She had won another huge landslide three years earlier and yet was losing control of her party. There were big revolts against some of her flagship policies.

In private, cabinet ministers suggested that she had gone slightly bonkers, one of the few allegations not being made against Sunak. The Tories began to lose by-elections with swings comparable to those happening now. By November 1990 she was gone, an act of regicide that disturbs the Conservative Party even now and fuels an outdated worship of her that intensifies with each new leader.

Thatcher went quickly, but the Conservative Party recovered to win the 1992 election. Yet John Major’s experience after his election triumph was much closer to those of Tory prime ministers who ruled after 2010.

From September 1992, when Britain left the Exchange Rate Mechanism, he navigated his way despairingly through one nightmare after another. Increasingly the party and his cabinet were split on Europe.

The media speculated feverishly for years that Major would be replaced by Michael Heseltine or Ken Clarke or Michael Portillo. In 1995, Major stood down as Tory leader while remaining prime minister, a humiliation that has not been experienced by the many prime ministers since 2010.

“We are in office but not in power,” warned the former chancellor Norman Lamont in his resignation speech, damning words from an ally of Major’s in the 1992 leadership contest. In 1997 the Tories were slaughtered, and were out of power until 2010.

The fall of New Labour was drawn-out, vivid and had about it a tragic symmetry. The dance between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown defined how Labour won triumphantly and also how it governed.

By the end, when Brown was prime minister, the dance became funereal. Some followers of Blair sought repeatedly to remove Brown as prime minister even when he was leading authoritatively in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash. They yearned to see David Miliband in No 10, without fully establishing whether Blair’s former senior aide was up for leading a coup or working out the precise route that made their hazy visions realisable.

The last attempted coup was in January 2010, the year of the election. This is not far removed from what might happen to Sunak if the local elections go as badly as feared.

When memories fade, the intensity of these falls from power appear less dramatic than what we are living through now. In each case, the implosions were deep and painful for those involved.

But here is the twist. Having revisited in detail the dying throes of previous postwar governments, the current epic decline is measurably far worse. Not a single member of Callaghan’s cabinets resigned over policy even though there were big internal tensions. They maintained discipline and a sense of unified purpose. Callaghan’s personal ratings were higher than Thatcher’s in the 1979 election.

Cabinet resignations were happening on a near-daily basis under Theresa May. Sunak has lost Raab and Suella Braverman, though Raab’s demise was not to do with policy differences.

When Thatcher fell, the cabinet regrouped and presented itself effectively under Major and Chris Patten as the party’s chairman. Major’s subsequent decline was brutal and the Conservative parliamentary party discovered an appetite for insurrection in the 1990s that it has not lost since.

But Major led a formidable cabinet. Ken Clarke was a popular chancellor. Michael Heseltine was a weighty deputy prime minister. They more or less kept the show on the road against Blair, the most formidable leader of the opposition in modern times.

The same applied to Brown’s rocky leadership. When he appointed Peter Mandelson as his deputy, there was a coming together of the two warring factions, Mandelson being seen as the personification of a Blairite in spite of his early friendship with Brown.

The financial crisis gave Brown fresh purpose. In the 2010 election, David Cameron did not win an overall majority in spite of enjoying a far softer media than Keir Starmer does now – little critical coverage from the BBC and non-Tory newspapers, outlets that gullibly assumed he was a “one-nation moderniser”.

Fin de siècle moods are common, but there has been none like this one as Sunak struggles pathetically, the fifth Tory PM since 2016. Some cite the collapse of the Tories in the early 1960s as similar, Harold Macmillan’s strange departure soon after he had sacked a large number of cabinet ministers in the “night of the long knives”, the Profumo affair and other dramas.

Yet the dazzling Harold Wilson only managed to win a tiny majority in the 1964 election and the Tories maintained discipline. They did not even move against their shy leader, Edward Heath, when he led them to a big defeat in 1966. Now there are volcanic eruptions on every front.

In spite of the threat posed by Reform, prominent Tories like nothing more than spending time with Farage at public events. Sunak’s No 10 is in demoralised chaos, a mood that feeds on itself.

Some Tory MPs and their newspapers scream for the UK to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. Others insist that would be a huge step too far. There are contradictory cries for tax cuts and increased spending on defence as well as on depleted public services.

All governing parties collapse in the end. What the current Conservative governing party is going through is a deeper existential crisis than a fleeting fall, similar to the one Labour experienced in opposition in the 1980s.

Neil Kinnock then began a long, stressful march back to a point where Labour was coherent and broadly unified over ideas and policies even though he did not win an election. Can the Conservatives do the same, and will it take them 18 years to return?

Where will the Conservatives turn next? No one knows for sure, and that is another sign of a government falling apart like no other in modern times.

Steve Richards’ latest book is Turning Points: Crisis and Change in Modern Britain. He presents the podcast Rock N Roll Politics