“Hasta la vista, baby”. Can you imagine Olaf Scholz concluding his last parliamentary appearance as chancellor with those words? No, I didn’t think you could.

In the manner of the man, Boris Johnson checked out as prime minister by boasting about his legacy and making light of the crises that his successor will have to contend with. Germans, in their baffling obsession with the curiosities of Britain, were intrigued by this closing gesture of the Clown King, seeing it in equal measure as both childish and titillating. If only their own politics could be such fun.

This, after all, is the same Britain with the second-worst-performing economy in the OECD (at least it is performing better than Russia), with rampant inflation, diminishing trade, labour shortages and increasing strikes. The country is ill at ease. But don’t expect its politicians to acknowledge that or show humility. Bombast has not died with Johnson. It

will under either Liz Truss or Rishi Sunak morph into a younger, albeit probably better behaved, form of the same. Except Sunak might be more

reluctant to don Thatcher garb and clamber into a tank.

Yet strip away the rhetoric, compare and contrast the actions of the two

countries at this time of conflict, and a contradictory picture emerges.

Why has a leader who has turned politics into performance, turned administration into a 24/7 bacchanalia, been hailed as a hero in Kyiv?

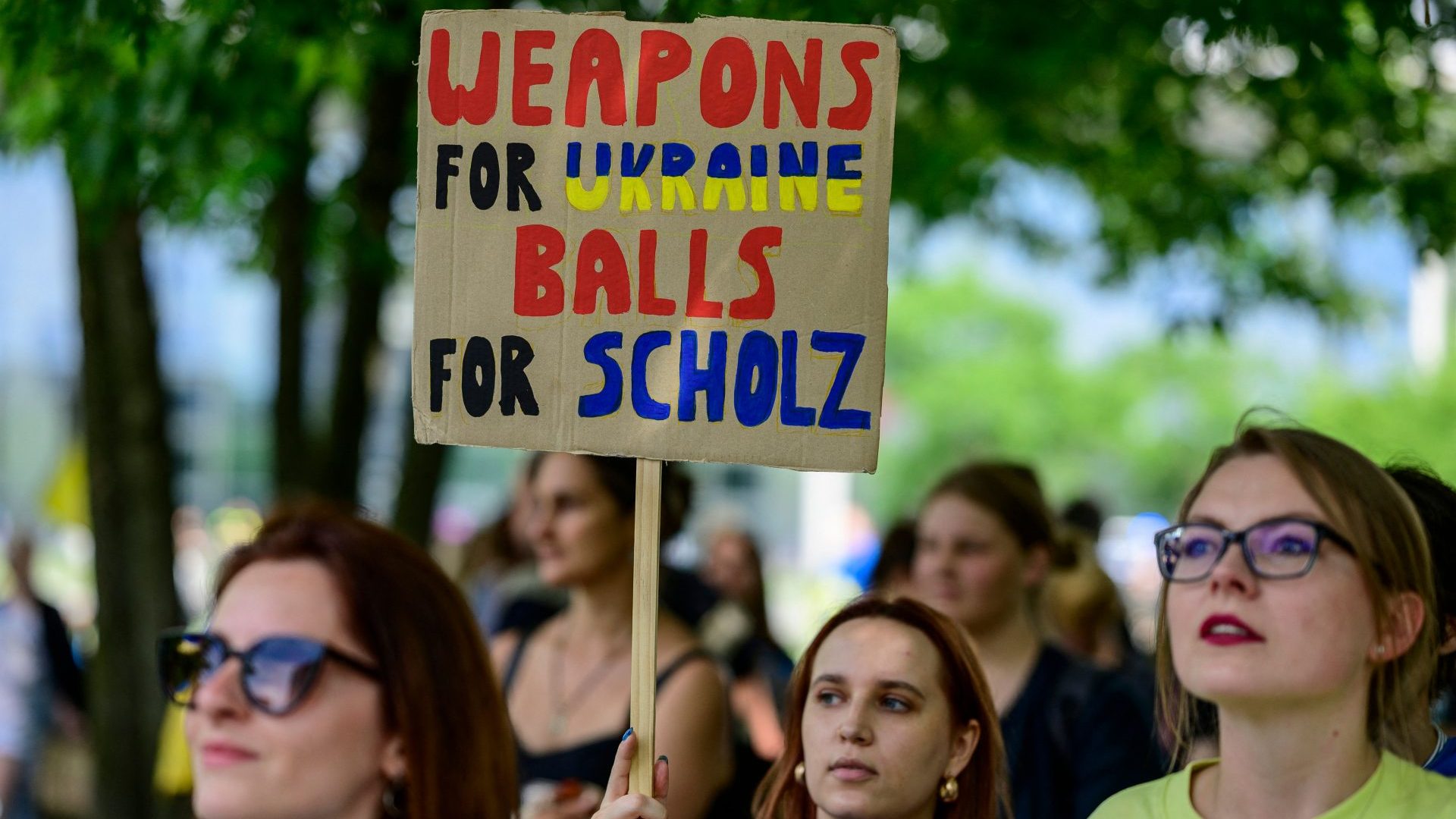

Why has the country that deliberates over politics so seriously, that talks

incessantly about the values of liberal democracy, so struggled to rise to the

challenge of Vladimir Putin and his invasion of Ukraine?

As an ardent Germanophile, I have been asking these questions with anguish. I did it, incessantly, over the past week in Berlin during an event that I was chairing. It is called Young Königswinter and each year it brings

together three dozen or so people aged between 25 and early 30s from the UK and Germany to discuss global issues. The three key themes were defending democracy in light of Ukraine, measures to combat climate (it was just as hot in Berlin as London) and the consequences of Brexit (a topic

that much of polite society in Britain now apparently considers out of bounds).

Few people have much good to say about Scholz’s approach to Russia and Ukraine. Some of this is unfair. After all, he was inheriting a legacy not just

of Angela Merkel but of a mindset dating back to the cold war. Germany couldn’t trust itself to become a geo-strategic power (the self-critical view); Germany was “over” militarism, it had found a higher calling (the arrogant view). Either way, the Americans were always there to defend them.

Five months into the war, the Bundeswehr has finally published a detailed list of arms shipments. It demonstrates that Germany is delivering – not as much as some (the United States is way ahead of the field) and not as much as it should – but it is delivering. Yet it is deeply uncomfortable in doing so and gains no credit for its contribution.

When I asked a senior figure in the government whether the problem was a) a failure of communication, b) a failure of strategy or c) the habitual kicking of Germany, which many in Europe love to do, he answered “all of the above”.

The person leading the charge was Ukraine’s ambassador, Andriy Melnyk. Week after week, he appeared on talk shows to denounce Scholz and his

reluctance to send heavy weaponry. Germany’s president, Frank-Walter

Steinmeier, was humiliatingly uninvited at the last minute to Kyiv as “punishment” for Germany’s long-standing relationship with Russia. The

final straw came when he defended Ukraine’s wartime figure leader, Stepan Bandera, a figure seen by ultra-nationalists as a freedom fighter, by most others as a fascist. Melnyk was reshuffled out of Berlin, to the barely concealed delight of the chancellery.

Across the German political system, the overriding impression is one of

beleaguerment and exasperation. According to one person present at the recent Nato summit in Madrid, Scholz unburdened himself over a glass of red wine or two after meeting the Spanish king about the treatment Germany was receiving. Germany was meeting its obligations, he is said to have complained – a statement that means everything and nothing.

This debate has been going on for a quarter of a century. When Joschka Fischer persuaded the Bundestag to back military action over Kosovo in

1999 (he had to invoke the lessons of Auschwitz to get it through), western

partners believed the Germans had turned a corner. They hadn’t. Defence spending went backwards. Germany may have sent forces to Mali, it may have participated in various European security initiatives, but was it ready to

really show muscle? In 2014 at the Munich Security Conference, the then

president, Joachim Gauck, warned his country it was time to stand up and be

counted.

Eventually, it did, or at least it seemed to. In its manner and substance, Scholz’s “Zeitenwende” speech on February 27 was remarkable. Having ambushed his coalition, he stunned chancelleries around the world with a declaration of intent that appeared to remove the shackles of the postwar era. Germany would finally meet the Nato requirement to spend 2% of GDP on defence and, as a start, would chuck in €100bn (£84.8bn) into the pot. In one fell swoop, it would become Europe’s biggest defence power.

What then happened, or didn’t happen, was equally remarkable. With opinion polls showing 85% public support for his intervention, the chancellor then applied the brakes. The government kept on not quite

sending military armaments. Even when it did, it didn’t let the world

know. Instead of setting out what Germany wanted to achieve, Scholz

talked about what Germany wanted to avoid. First and foremost, nuclear annihilation. Everyone wants to avoid that. It was little more than politics as

truism, hiding behind public anxieties as faux justification for a lack of leadership.

The lack of military expertise hasn’t helped. On TV and across the media, military historians and specialists are thin on the ground in a country that

instinctively recoils at the subject of warfare. Into the void has stepped in a

predictable group of 1968ers, who still recite the mantras of the peace movement of past generations.

One of the most trenchant spats took place in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit, involving the philosopher Jürgen Habermas and the (comparatively younger) American historian, Timothy Snyder, each of whom set out their wildly different stalls.

For Habermas, it was the usual cocktail of Germany’s war guilt, infused with standard scepticism about Nato. Snyder accused him of “writing from the perspective of a sentimentalised West Germany in the 1970s”. Habermas, he said, “presents Germany not as a major democracy with power and responsibility, but instead as the Kremlin would like for Germans today to see it: as a pawn in a larger game, with no choice but to submit to larger realities.”

These rhetorical barrages fail to reflect a more nuanced picture. The perception of Germany’s response is worse than the reality. But the failure

to more positively project the role the country has played is part of a historic

problem. Scholz faces immense difficulties in persuading his population to unlearn all the lessons of the past 80 years and to welcome the shipment of heavy weaponry. His discomfort is deep.

At the same time, Germany is giving Ukraine enormous financial aid, while

accommodating unprecedented numbers of refugees. Unlike in Britain, few questions are asked at a time of emergency.

The economics ministry, under the impressive Robert Habeck, is detailed

and thoughtful. In just a few weeks, he has already diversified Germany’s

energy requirements away from Russia. The original pipeline, Nordstream I, has been turned back on by Moscow, albeit operating at well below half capacity. Ministers assume it is just a matter of time before Putin switches it off. Gas reserves are being built up; the population is being warned of a tough winter ahead.

The Greens were the first to be apprised of the dangers posed by Russia and China. Even some in Scholz’s Social Democrats, the traditional home of Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik and pro-Russian sentiment, are waking up. Lars Klingbeil, who took over as co-leader of the SPD last December, gave an extraordinary

recent speech that was a clarion call for action and for the jettisoning of old

assumptions. Germany, he argued, had become all too comfortable, assuming the Americans and others would do its dirty work.

“It was as if people thought that the smaller the Bundeswehr becomes, the less the chance of war. The opposite is the case.” And, in a stunning break

with the past, he added: “Germany must lay claim to be a leading power”.

Scholz would never go that far, but over the past few days, he too has shifted. In a commentary for the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper, he called on Germans to take a deep breath and prepare for the long haul. A victory for Putin, a victory for aggression over international law, would hold greater dangers for global democracy, beyond the territory of Ukraine. For once there is no obfuscation, no vague talk of peace. Psychologically that is new territory, but will this be a sign of things to come, or, as after his speech on

February 27, another false dawn?

Call it Vergangenheitsbewältigung 2.0. Adapting the lessons of the past for this new dark era, convincing Germans that war is not the worst outcome. Succumbing to dictatorship is.

For all Germany’s woes, a look elsewhere is salutary. The US under Joe Biden has been forthright in its support for Ukraine and shipment of weapons. But it is teetering under the weight of social and economic malaise. Trump or Trumpism may be two-and-a-half years away. More than 60% of French voters opted for parties of the extreme. As for the UK, the defenestration of Johnson marks merely the passing of the baton, but expect more breaking of international law, more bellicosity. Seen from Germany, Britain seems an increasingly distant land.

Serious, deliberative politicians should not have left courage in standing up to Putin to those governments who wear their commitment to democracy lightly. This should have been Germany’s moment to stand up and be counted. In this protracted era of warfare, it could yet be. But if it does, it won’t come easily.