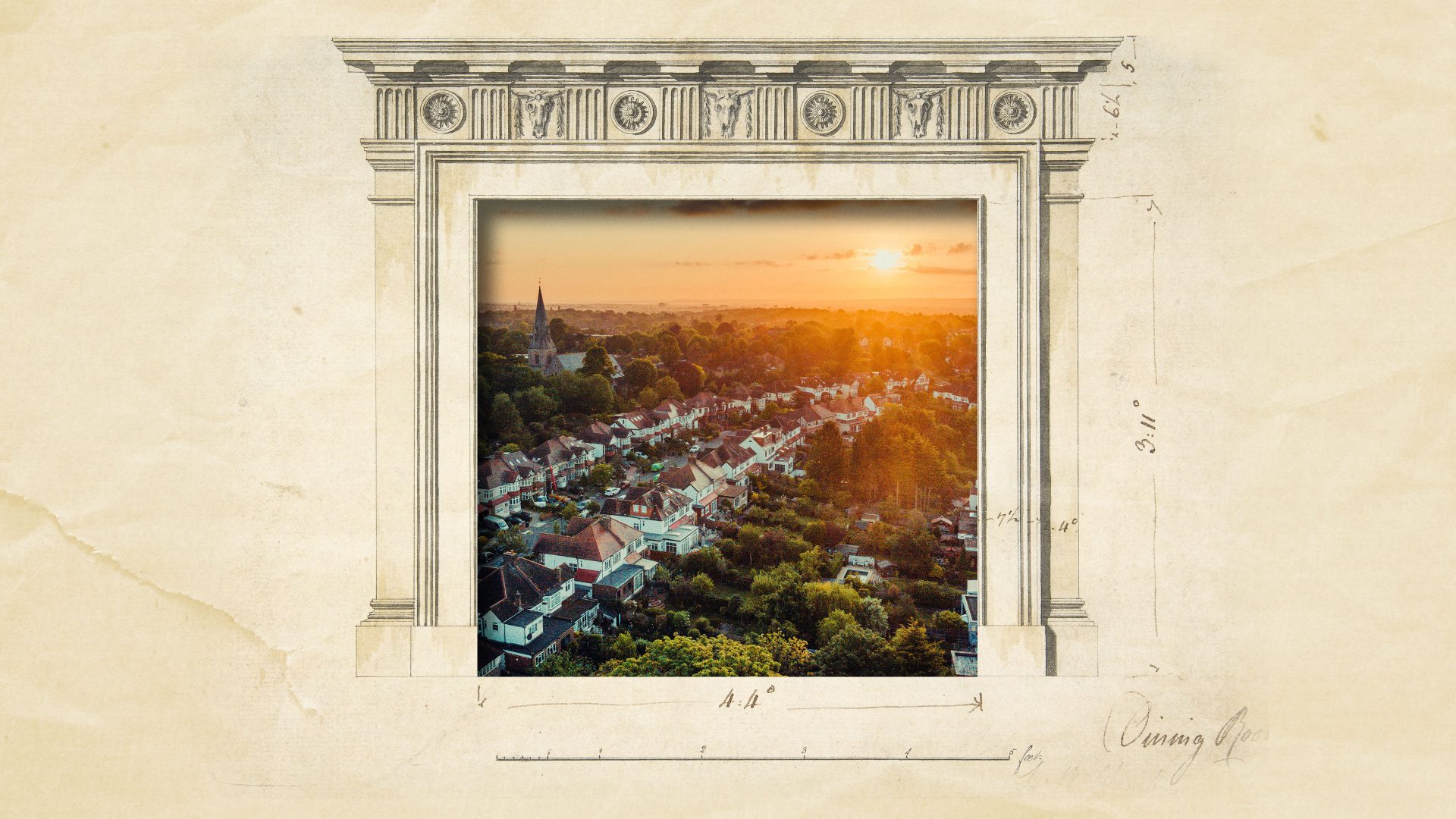

To begin with, it was the fireplaces that confused me – and in retrospect, this seems apt: for if any house can be a home, it can also be a sort of wormhole, dispatching even the humblest suburbanite into their past. Britain has some

of the oldest housing stock in the world – if it weren’t for the colossal public building project that lasted from 1945 to 1975, most of us wouldn’t have an indoor toilet/pot to piss in. Now, successive governments “struggle” – not very convincingly – in the serpentine embrace of developers and cash-starved local administrations, who together effectively operate a price cartel predicated on the absolute necessity for Mr & Mrs Valetudinarian-Daily-Mail-Reader, to hang on to the inflated equity in their equally agéd homes, until it’s prised from their cold, dead hands.

The fireplaces in our newly purchased house just didn’t jibe with its exterior; which is the type of bow-fronted, white-harled or red-tile-hung terraced or semi-detached villa that lines the arterial roads uncoiling from British town and city centres. This massive suburban development is something we associate – along with the bowdlerisation by spec’ builders of ancient vernacular styles – with the interwar period. Out of the Neogothic, by way of the Arts & Crafts movement, bodied forth row upon row of faux Tudor, Jacobean, and latterly Queen Anne houses, each one a little castle – complete with its pocket-demesne.

This tendency in the collective British psyche towards uchronia – a time that never was – rather than utopia, should gladden the King’s heart, since his entire raison d’être is the preservation of crumbling institutions; a philosophy reflected in his own piss-poor Potemkin village of Poundbury. Not, of course, that the system-builders of the post-war period should be spared our ire: their cut-rate Le Corbusier point-and-slab blocks were a socialistic fever

dream of equality and collectivism: an imagined future to balance against the conservatives’ irreal past. One that’s now degenerated into UPVC window frames oozing black mould, and rack-renting landlords forever exercising their right to evict.

The fireplaces confused me, because with their neoclassical surrounds – featuring pilasters, laurel wreaths and swags – and their cast-iron hoods and grates, and their hearth and cheek tiling in distinctive eau-de-nil and cerulean shades, they seemed irrefutably late Victorian. The bathroom didn’t help either, what with its sea-green porcelain sink, bath and commode, and its sea-green and black tiling – because if the house had been built in 1930, which was what the agent told me, such an assemblage would’ve been absolutely contemporary. My conclusion? The four fireplaces must be fakes: little uchronic houses for the gentrifying modern Britons’ fire gods.

I was disabused by a neighbour as nerdy as I when it comes to these matters – the little terrace of six Arts & Crafts houses of which our two are part is just that: a very early phenotypic example of the genotype to come. Built in 1910, and heavily influenced by Norman Shaw, the great conceptualiser of suburban style, the house’s fireplaces are entirely original: nine years don’t really constitute an anachronism in the built environment, unless they include a war to end all wars.

Our initial attraction to the house was that it seemed to have so many original features still intact: built-in scullery cupboards, enlarged dado rails, and of course the aforementioned bathroom – which we now realised was an

egregiously modern addition.

The trouble is, now we know we’re occupying an authentic little Edwardian house… we’re keen to enhance its, um, relatively agéd status. We want to dive into those fireplaces and reach a quieter, less fraught time. Obviously,

we don’t want to think about the rampant imperialistic arms race, the disenfranchisement of women, and the hopelessly squalid working-class housing that also typified the era. Our youngest, who’s living at home again just now, calls us “period fascists” – which sounds uncomfortable: but it cannot be denied, we’ve taken to searching for Edwardian furniture online, as well as attending antiques fairs and markets.

We don’t have a huge budget – but that isn’t altogether necessary; as I’ve had cause to remark in this place before, when it comes to pricing the past in cash terms, for the most part it’s undervalued. The glaring exception being property itself. As for my own proclivities, well, I always thought I’d end up in an echt minimalist apartment on the 40th floor of some mega-block, yet here I am: back in the sort of uchronic suburbia, the privet-lined precincts of

which I spent my childhood trying to escape.

Eliot was right: the end of all my exploring has been to arrive back where I started, and to know the place properly for the first time.