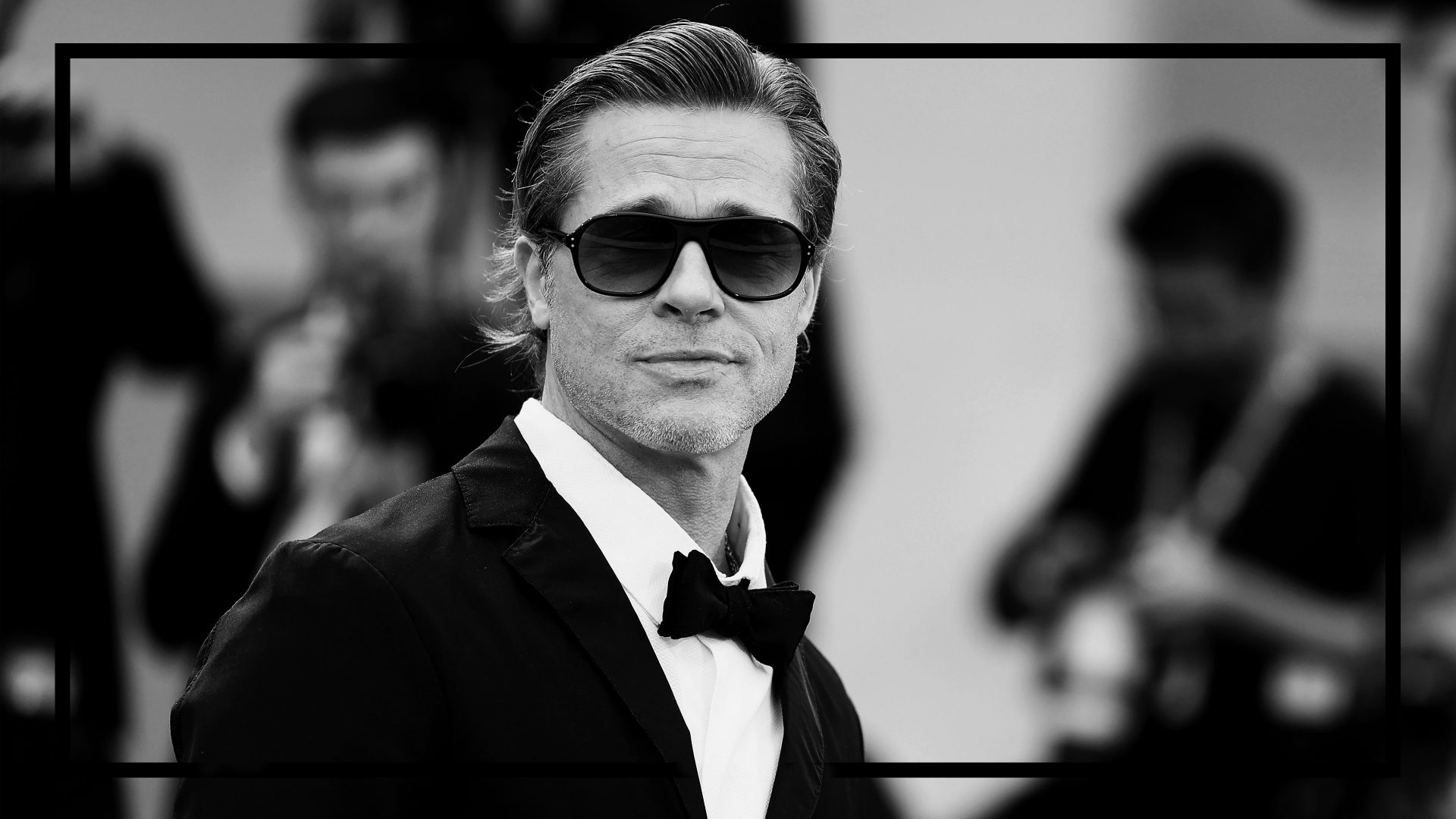

Brad Pitt, who’s engaged in a protracted and unseemly battle with his ex-wife, Angelina Jolie, ostensibly over their shared ownership of a French vineyard – but really over child custody – has been reported widely in the press talking about attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in order to get sober. Look, I understand that one of the most obvious things about actors – especially those who achieve great fame and distinction – is that their actual personalities are quite at variance to those of the characters they portray, but c’mon, literacy, right – I mean to say, Pitt can read, can’t he? And we’re not talking about a lengthy screed here, but just the one word, “anonymous”, which when I last looked was defined as “(of a person) not identified by name”.

It is worth considering for a moment how it is that a self-help organisation based firmly on the principle and practice of its members not being publicly identified by name came to embody the exact opposite – so much so that a change in its own name seems overdue. Can we perhaps start talking about Alcoholics Notorious, and moreover applying this to all of the formerly “anonymous” fellowships – as they further style themselves – from Narcotics through to Over-eaters.

The Twelve Traditions of AA sum up the organisation’s collective ethics in a way analogous to the manner in which its Twelve Steps set out a programme for the moral restitution of its members. The two traditions concerning anonymity are the last and most important ones. Tradition 11 states: “Our public relations policy is based on attraction rather than promotion; we need always maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio and films.” While Tradition 12 figures anonymity even more importantly: “Anonymity is the spiritual foundation of all our traditions, ever reminding us to place principles before personalities.”

Founded during the Depression by an out-of-work stockbroker and a small-town doctor, it’s easy to see why in the censorious culture of an America only just recovering from the moral depredations of Prohibition, alcoholism remained a terrible stigma. But while in the first instance anonymity was seen as protecting the individual member at the point when they join the group, even more important was the insight that if recovery from alcoholism was seen to be embodied by any given person, active alcoholics would be more likely to dismiss it.

It’s obvious why this should be: if someone famous (such as Brad Pitt, for example) brutes it about that he’s dealt with his demons in this way, then falls – just as publicly – off the wagon, the entire programme suffers collateral damage. There’s this, and the notorious judgmentalism of people

afflicted with addictive illnesses, who feel themselves both duty-bound – and compelled by their malady – to trash any possible means of rehabilitation on any basis whatever. Famous piss-artists giving interviews in which they prate

on about how the road of excess has led them to this particular palace of wisdom (more accurately a circle of plastic chairs in a community centre), far from attracting less their exalted fellow-sufferers, is more likely to repel

them altogether.

Should we care? After all, when assayed by the sort of people who study these things – and, of necessity, quantify them – the anonymous fellowships aren’t conspicuously successful when it comes to promoting long-term sobriety. But then they would say that, wouldn’t they, because whatever else the efficacy of the AA programme rests on, it isn’t the expertise of doctors, psychiatrists or professional counsellors – being intrinsically anarchic, with individual groups taking on their character from the culture in which they’re embedded.

Which explains, in turn, what’s gone wrong. No less an authority than the founding father of psychology, William James, asserted: “There is no known cure for dipsomania other than religiomania.” And he didn’t mean this pejoratively – the AA programme attempts to institutionalise the conversion experience James saw as integral to recovery from the malady, which is why the G-word is to be found scattered liberally throughout its 12 Steps. Of course, in our secular societies there’s no place for a supernatural healer, and many AA members default to regarding their home group, or some other beneficent collective, as their “higher power”. It’s easy, in turn, to

understand how a notorious film star, habituated to the bizarre confessional of being interviewed by the press and for radio and film, might perceive the media itself as a kind of warped higher power.

Moreover, given that social media so evidently are a higher power for so many, it’s next to impossible to imagine contemporary alcoholics’ recoveries not being dramatised in this fashion. A cynic might say all they’re doing is

swapping one addiction for another. I am that cynic.