What’s the connection between goldsmithing techniques developed in the 13th century and the magical suit sometimes worn by the eponymous hero of the Super Mario computer games franchise – one that allows him to fly, use his acquired tail as an offensive flail, and metamorphose into a statue? The answer is, of course: testicles; specifically, the proportionately large testicles of the Japanese tanuki, or raccoon dog.

Would the average contemporary Japanese be able to give the right answer, and elucidate all the linkages between these two cultural phenomena? Probably not – yet a consideration of just this is highly illuminating when it comes to understanding the conjunctions and disjunctions of East and West to this day.

The Kamakura period (1185-1333) is mostly known for the emergence of feudalism in Japan, together with its political sequels: the first shogunate, and the samurai warrior caste. But there was a lot of tanuki testicle-bashing

going on as well: the creatures’ scrotums were used to soften the mallet-blows as goldsmiths hammered leaf into being. This comical image of the stretched and expanded scrotum then became integral to the animals’ mythic power: shrouded in their giant ball sacks, the raccoon dogs transformed into powerful shape-shifters, more than able to hold their own in the polymorphously perverse realm of Japanese myth-making.

And, of course, they still do – not just appearing by proxy in the Super Mario games, but also under their own guise in the 1994 Studio Ghibli film, Pom Poko. Indeed, much of the action of this eco-fable consists of the loveable and bumbling creatures (which is how they’re also traditionally portrayed, withal their supernatural powers) employing their massively extendable scrotums to defend their woodland home against the depredations of Tokyo’s

breakneck expansion.

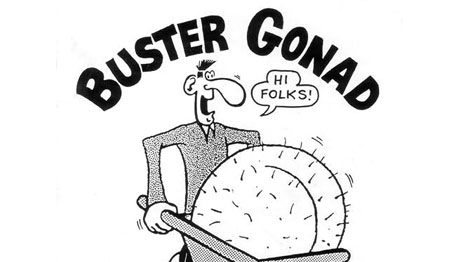

I confess, despite my own avowed multiculturalism, I’ve struggled to find any entity in British myth, fiction, or indeed reality that uses its scrotum in such an extravagantly creative way. The only exception being the Viz comic

cartoon character Buster Gonad, who is compelled to cart his “unfeasibly large testicles” around in a wheelbarrow. Gonad does indeed interpose his grotesque gonads to all sorts of troubling situations – but his resolutions tend to be painfully bathetic rather than endearingly silly. I see these

appendages as having sprouted from teenage boys’ horror at their own burgeoning sexuality; and perhaps also an exposure to images of men afflicted with elephantiasis of the testicles – which certainly haunted my own adolescent imagination.

Still, the possibility has to be considered that Viz artist Graham Dury did indeed find his inspiration for the Gonad character in the Japanese tanuki – or, more specifically, its supernatural alter-ego, known as a bake-danuki. The timing isn’t quite right though: while Japanese mythology is of course present in the West prior to the mid-1980s, it’s really the vectors of anime cartoon and its associated media – computer games, films – that spread knowledge of these strange beings more widely.

This being noted, the origin story of Buster’s knackers does seem reminiscent of the Kaiju – or “strange beast” – genre of postwar Japanese films, the most famous of which is the first, Godzilla (1954). The massive enlargement of Buster’s nadgers was – Dury tells us – the result of them

being zapped by “cosmic rays” during a storm; and this seems congruent with Godzilla’s genesis: a giant prehistoric reptile, awoken from immemorial slumber and hugely empowered by the radioactive fallout from the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Can we extract some grand theory of trauma out of this – one uniting East and West in a gooey confluence of bio-horror? I suspect not. To return to the tanuki: their extraordinary anatomy is viewed not in any prurient or

sexualised way at all – Pom Poko is a children’s film, and even on Netflix (where can view it for free if you have a subscription, there’s no trigger warning about these private parts receiving so much, um, publicity.

Can we then, contra-wise, view the tanukis’ capacious cojones as evidence of an animism still alive in Japanese culture and folklore, but long since exiled to the periphery of the western imagination? After all, just consider quite how toothless and neutered most of the creatures are that feature in contemporary western children’s media.

Well, yes, I would say so – but then this might well just be yet another instance of Orientalist othering on my part; after all, for all I know contemporary Japanese people may think the whole bizarre tanuki conception to be nothing more than a load of… balls