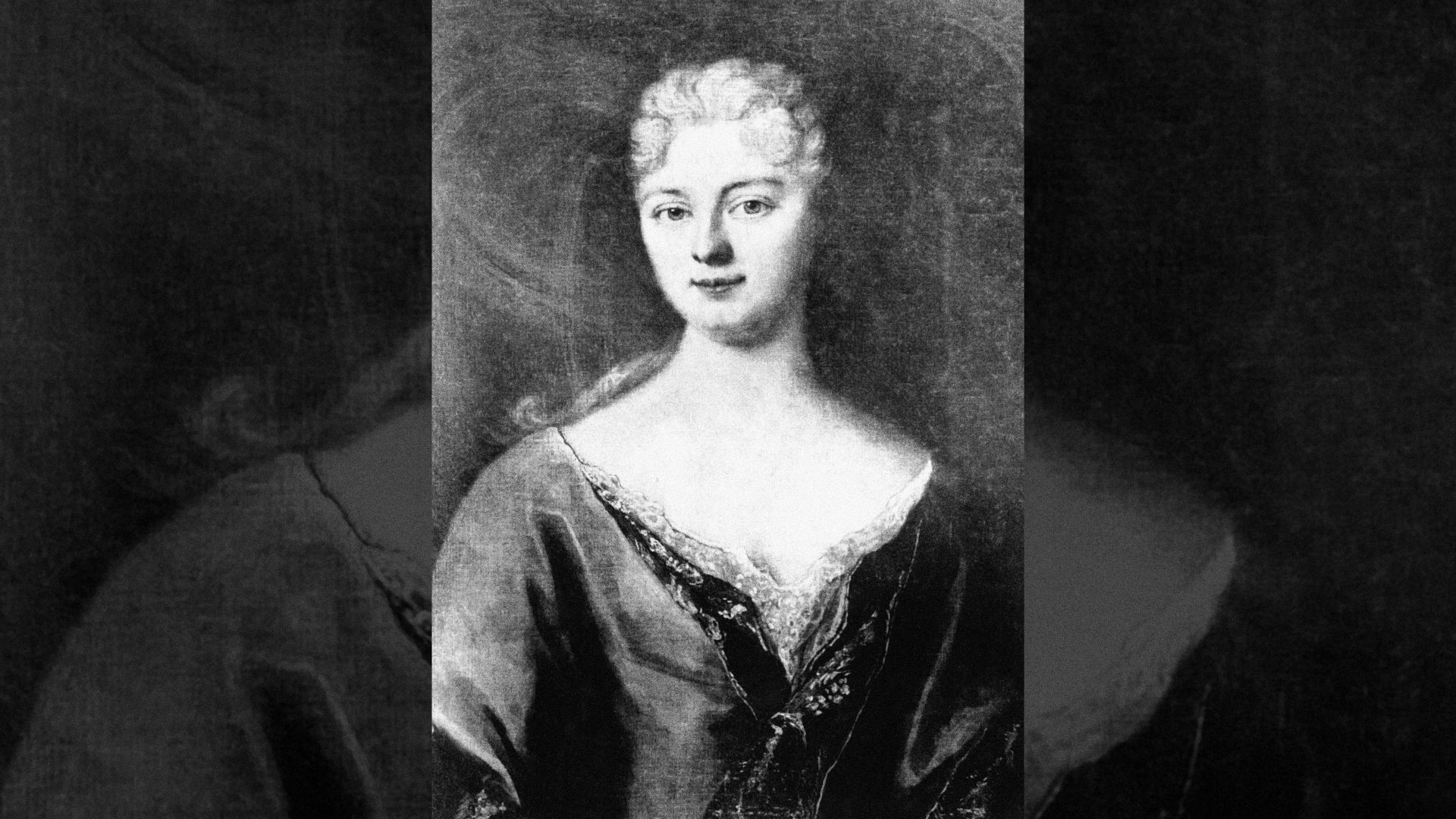

Shout out to Françoise-Louise de Warens – aka Maman – who I like to think of occupying the storied position in the afterlife she so fervently believed (believes?) in, and which she deserves to have in this pre-death we all share. She died, in poverty, in Paris, in 1762, in a France still seemingly firmly in the embrace of the Ancien Régime, with all its celestial pomp and gold-encrusted circumstance – but the revolution de Warens began started long before – and is still going to this day. She may have a far less familiar and illustrious name than her former lover and protegé, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, but she deserves to be seen as the founding Maman not just of the philosopher’s radically new worldview, but that of European culture as a whole.

As to why we should celebrate her now – why not? In the immortal words of George RR Martin, “Winter is coming”, and, as the winds rise, I for one find it comforting to think of the arcadian life young J-J and Maman led, together with the third member of their throuple, the herbalist and scholar, Jean Amet, at Chambéry in the Savoy Alps.

Rousseau lived with de Warens on and off for around a decade, if his own posthumously written Confessions are to be believed, and during that period he went from being a gauche 15-year-old runaway – the son of a widowed watchmaker and Genevan political malcontent – to a young man on the cusp of a brilliant career as a thinker and writer of compelling persuasion and originality, as at home in aristocratic salons as the dwellings of the poor: the activator, as it were, of the liberal transformation of European society in the 18th century.

I wonder if this extraordinary transformation would have been possible were it not for Rousseau learning how to live and love not just with a woman, but another man as well? There’s no suggestion in The Confessions that his relationship with Amet was a sexual one, but Rousseau is unashamed in declaring his love for this man, whose untimely death ended this phase of de Warens’ extraordinary social experimentation – but by no means the overall project. As well as having a pragmatic view of sexual relations between consenting adults, de Warens was a sort of earth mother avant la lettre.

Her main thing was botanising with a view to concocting herbal remedies. Yes, it’s polyamory and lavender pillows! How modern is that! But she also had an extensive library, was widely read herself, and consorted with a group of Savoyard intellectuals, many of whose members were Catholic clergy and local Catholic gentry; associations determined for de Warens by her own circumstances: an aristocratic scapegrace and convert from Protestantism, her lifestyle depended on a sinecure paid to her by the Catholic church in order to entice other Protestants “back” to the old religion.

Yes, that’s right: all of this alternative living depended on a religious orthodoxy she sought to extend to the orphaned Rousseau, to whom she acted initially as a mentor, before eventually taking him to her bed. Posterity has not looked altogether kindly on him – in our era of the grand re-evaluation of all values (one, arguably, the permanent and revolutionary character of which he did much to anticipate), he’s remembered as a paranoiac who may have given as many as five of his own infant children up for adoption. Babies conceived with a working-class mistress, whom Rousseau himself said was of low intelligence, and came from an exploitative family background.

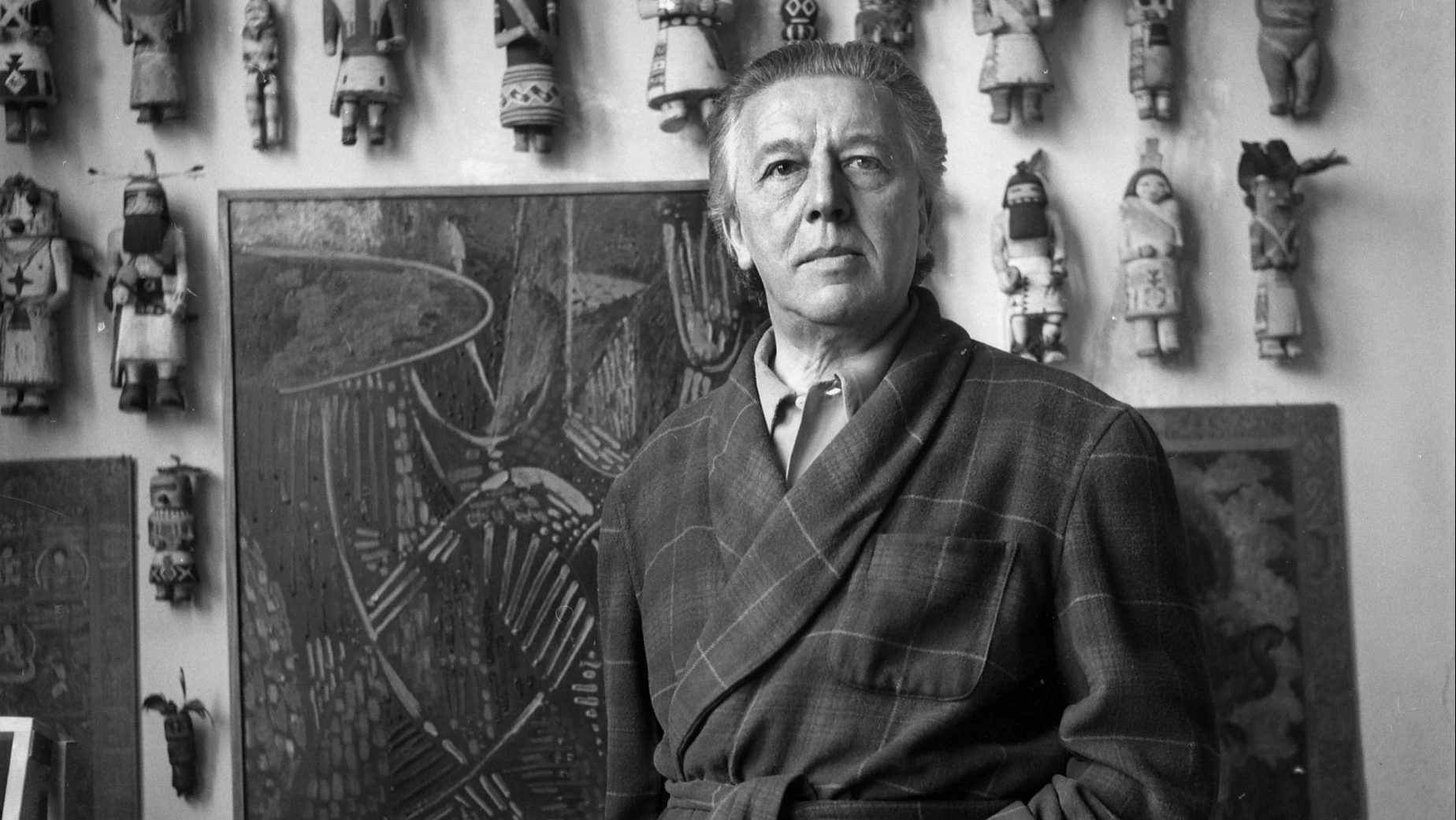

The social-contractarian philosophers – who hypothesised the existence of a “state of nature”, either freed from or prior to the constraints of civilisation – are often dismissed as childless men who’d forgotten their own childhood; but of course, Rousseau was pretty much the antithesis of this: a philoprogenitive man who ’fessed up to the sordid little intimacies – masturbation, pilfering etc – of his own childhood, in such a way as to leave you in no doubt that he remembered it only too well.

No, he and de Warens – a childless woman, who, whatever you think of her source of income, managed her own financial affairs in a patriarchal era – were the archetypal moderns, and their religious conversion is intrinsic to this: since latitudinarianism is, of course, the altar upon which the smorgasbord of contemporary political choice is lain out. Choice that includes whether or not to have children – and by extension, whether or not to bring them up in any particular way, or even at all.

That the author of the most celebrated text on education in the 18th century should also have been a deadbeat dad shouldn’t surprise us any more than his near-contemporary and fellow iconoclast, Voltaire, being a raving antisemite. You can’t keep all the babies if you want to throw out the holy bathwater.