I think the cultural highlight of my life has been a performance of John Cage’s 4’33” I saw at the Royal Festival Hall in the 2000s. I can’t remember exactly what it was about this particular rendition of the piece – for I have attended many – that so struck me; neither can I recall the pianist’s name – but whoever they were, they brought to Cage’s ineffable score that sense, simultaneously, of utter engagement – yet total absence – that distinguishes the authorial presence of Pierre Menard in his Quixote, from Cervantes’s in his.

I digress – nevertheless, perceptive reader that you are, you’ll have already realised where I’m going with this: a Parisian friend came to visit this week and brought madeleines – and not just some vaguely shell-shaped chunks of spongey cakeness: these ones are well-formed, sizeable cakes, flavoured with Madagascan vanilla, and marketed under the tradename Chez Marcel, no less. The founder of the marque, Maxime Beucher, joined with Camille Lesecq, who was for eight years the patisserie chef at the Palace Hotel, to “redonnent vie á la Madeleine de notre enfance”.

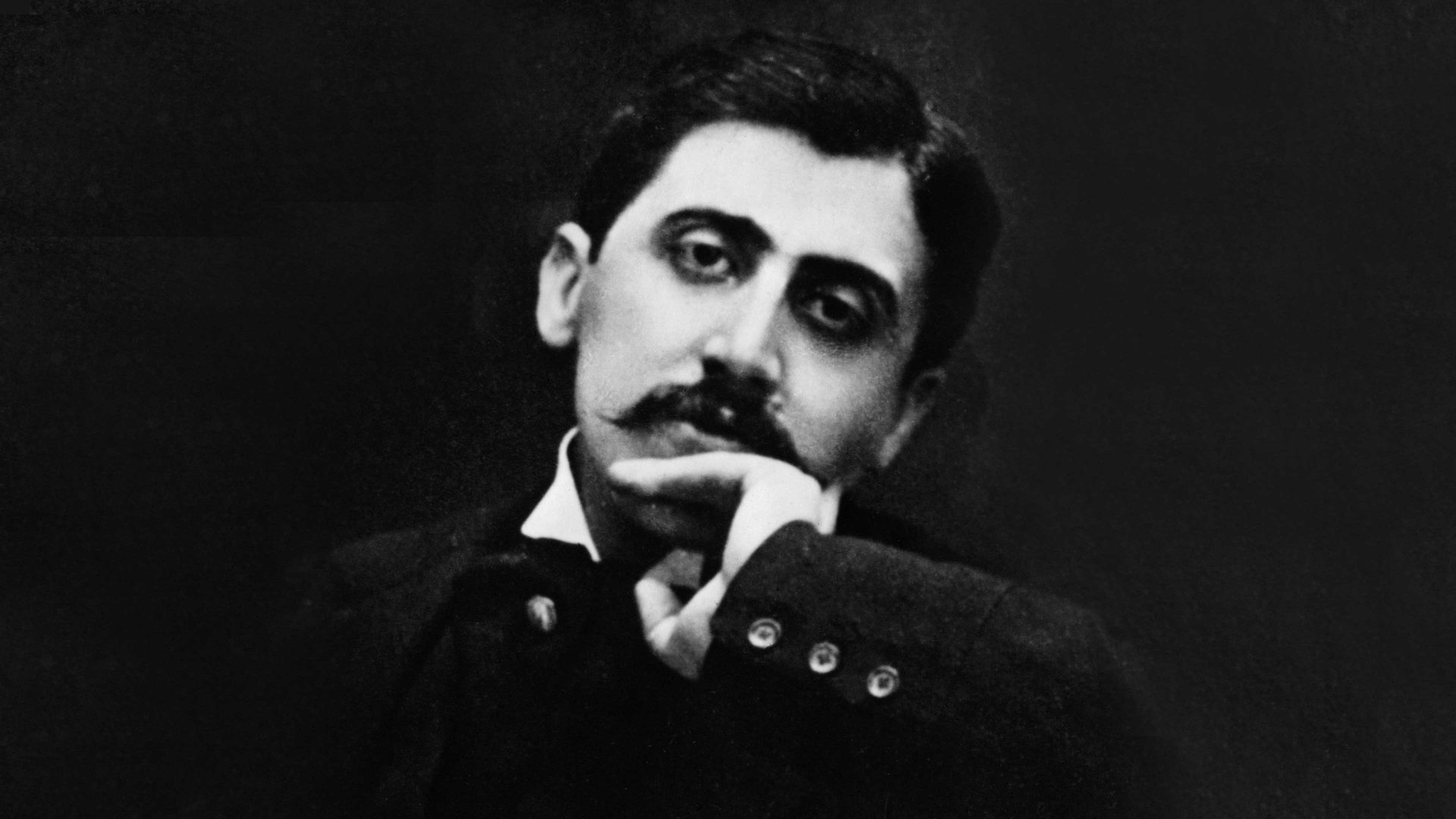

Not of mine, I have to say: there weren’t a lot of madeleines in East Finchley in the 1960s and 70s; my own Maman was, however, a committed Proustian, and imparted in me the conviction that unless these words – which also adorn the packaging of Chez Marcel’s madeleines – aren’t engraved on your heart, you don’t have one: “Et tout d’un coup le souvenir m’est apparu. Ce gout c’était celui du petit morceau de madeleine…”

Yet, if I take a little morsel of one of these madeleines, put it in a teaspoon, and dip that in my tea; when I place it in my mouth, the taste of the dissolving cake doesn’t summon memories of my childhood, but those of my early manhood – which is when I read the first six volumes of Proust’s monumental In Search of Lost Time. Much of it propped up against the bar of the Victoria Hotel in Darwin, in the remote Northern Territory of Australia – about as far from the etiolated environs and rarefied lives of those denizens of the Faubourg St Germain with which the notoriously prolix prosodist was preoccupied, as is imaginable.

Or, at least that’s what those who are intimidated by the synecdochal character of Proust’s style – each paragraph, in its extent and sinuosity, replicating in miniature the whole winding course of this mighty roman fleuve – say about the novel; for my part, withal the 35-degree heat, and notwithstanding the steady fleuve of Emu Export (which, if I remember rightly, was 20c a schooner in 1983), served near-ice-cold straight from refrigerator units, I loved it. Indeed, the aggressively egalitarian matiness of the Territory at that time made a refreshing contrast to the seemingly petrified social hierarchy described in Swann’s Way and the rest.

Not that Proust doesn’t show that this semblance is beginning to crumble, as the pressure from below becomes increasingly relentless. At the Victoria Hotel, a large mechanical punkah wavered back and forth over the drinkers – overweight, red-faced white men, wearing obscenely short shorts and drinking from glasses filmed with condensation, that were refilled by the barman as soon as they were emptied.

No words were exchanged: he simply subtracted another 20c from the pile of change each man had on the bar in front of him. I turned another page, took a long draught of beer, and lit another cigarette – there was bugger-all else to do. Outside, in the afternoon heat, all along the median strips of Darwin’s wide boulevards, and beneath the pandanus, sat Aboriginal people, silent and brooding. The whites – with their compelling literalism – called them “the Long Grass People”.

As I say, I read the first six volumes of Proust propped up against that bar in Darwin – and decided to leave the seventh, Time Regained, for my old age. Well, what with the cancer, and the looming stem cell transplant, I’ve decided to have my retirement early, so have been Chez Marcel for a few weeks now. Weeks? Yup – because, truth to tell, apart from a few of the major set-pieces, the overall tone of the work, and the outline of its principal characters, I’d pretty much forgotten the bulk of the 3,000-odd pages I’d read 40 years ago, so have reread them.

Some of those pages are very odd – and in fairness to those who struggle with the work, some of his longueurs are near-insupportable, as is his ineradicable social snobbery, together with its assumption of bizarre entitlement. But what is extraordinary about In Search of Lost Time, is precisely its attention to the passage not of individual, but social time: Proust notes acutely the inception of the specular media of the 20th century, with their implications for the mechanical reproducibility of artworks.

John Cage would have understood.