Granted, it’s a niche concern – and to ask you, my readers, to share it, would be akin to asking you to parallel park the magnificent and ornate vehicle of your conscience in a horribly constricted space; however, since they’ve been

costing me sleep with their coruscations, I cannot forebear. Yes, as you’ve doubtless already realised as I deployed this elongated – as much as extended – metaphor: I want to talk about streets, and the enfilades of lamps thereon.

Specifically, I want to talk about the old gas-lit streetlamps, with their inverted-pyramidal lanterns topped by Saracen spikes, and their standards equipped with ladder bars, such that likely little Cockney lads can scamper up and light them, while honest coppers who’ve never exchanged racist banter on social media with their colleagues (because social media hasn’t been invented yet), stroll past twirling their truncheons.

I want to discuss these streetlamps because while there remain about 1,500 of them in London, where I live, over the past few years there’s been a concerted move by local authorities to replace their gas burners with LED arrays, and their cast-iron stanchions with modern replicas. Now with a rush and a push, Westminster council believe the land is theirs – and are trumpeting their success in replacing a further 30 of these ancient torches, while claiming that the retention of the remainder represents an environmental hazard. Other arguments used for the abolition of the old lamps are that their yellow and buttery light merely gilds criminal enterprise, rather than exposing it to the possibility of interdiction by… um, the sort of bent coppers the Met is currently cluttered up with.

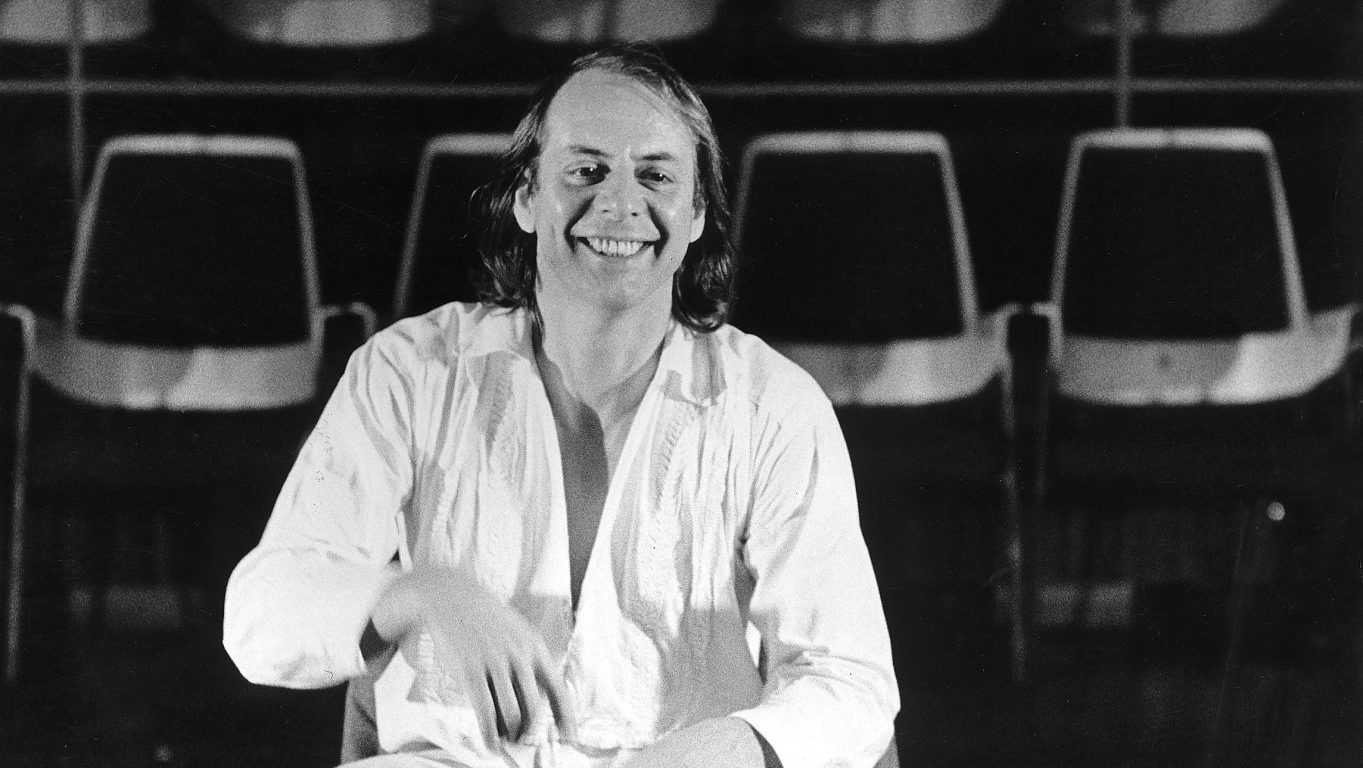

The orotund-voiced actor Simon Callow, together with other campaigners, has urged the council “to reconsider this disastrous policy”. They argue on economic as well as environmental grounds, asserting that the repro’ lights

won’t pay for themselves for another 13 years.

This seems a mistaken line to take to me: ceding the ground to those who know the price of everything but the value of nothing. You don’t need to be some sort of Victoriana re-enactment freak in order to appreciate the gas lamps: the light they give out simply is more beautiful – and aesthetics can never be reduced to economics.

On the environmental issue, a better argument is supplied by Tim Bryars of the risibly named The London Gasketeers campaign group, who observes that: “In Phoenix Park, Dublin, 244 lamps contribute to the park’s status as a dark skies oasis.” Why? Because they’re nothing like as bright as the LEDs or other electric lights, and so allow wildlife – as much as humans – to feel they’re subject to circadian rather than merely municipal rhythms.

As for the argument that having brighter lights is part of designing against crime – how well has that really gone overall? Britain’s addiction to CCTV is such that we’re already the most surveilled nation in the world; it’s difficult not to conclude that one of the real reasons we need brighter streetlamps is so that it’s easier to catch malefactors on film – or deter them because they believe they may be. The transformation of the entire country into a giant zone of potential malfeasance is, I believe, the objective correlate of the way our civil society has deteriorated.

The great American urbanist, Jane Jacobs, believed the safety of cities depended on what she termed “the eyes on the street”: usually older people who made it their business to observe locales and know the people who used them. In place of this personalised presence, we now rely upon the anonymous and the absent to make us safe – instead of the eyes on the street, we have those on the screen.

Obviously, I wouldn’t be quite as exercised about this as I am if it weren’t personal: we moved house recently, into a conservation area with largely late 18th and early 19th- century houses. Ours is an anomaly: a little Arts & Crafts-inflected 1910 terrace with a white-harled bow-front, and outside on the pavement – you guessed it – a reproduction gas streetlamp equipped with an LED array.

The light from this streetlamp is so white and bright it rouses me every night – despite thick and well-hung curtains – and beckons me towards some sort of dystopic Narnia, where time has stopped, it’s always winter, and a succession of wicked and witchy leaders rule over a cowed populace – bribing the corruptible with the promise of Turkish delight in the form of windfall profits, punishing the poor with a stony lack of any social security. In other words: contemporary Britain.